Where Are My People? Queer in Architecture

Where Are My People? Queer in Architecture

Chris Daemmrich, Assoc. AIA, NOMA (he/him)

Michelle Barrett, NOMA (she/her)

My-Anh Nguyen, AIA, NOMA, LEED Green Associate (they/he)

Kendall A. Nicholson, Ed.D., Assoc. AIA, NOMA (he/him)

October 18, 2024

Advocates for equity and social justice in the built environment assert that architectural agency in the United States is most commonly tied to capital. To forefront equity and social justice, ACSA has advocated for a future that reconnects the practice of architecture to all the people it serves. Started in 2020, Where Are My People? is a research series that investigates how architecture interacts with race and how the nation’s often ignored systems and histories perpetuate the problem of racial inequity. In 2024, the series expands to include other marginalized populations, starting with the LGBTQIA+ community. In partnership with Emergent Grounds for Design Education, Where Are My People? Queer in Architecture chronicles both societal and discipline-specific metrics to highlight the experiences of LGBTQIA+ designers, architects, and educators.

The term LGBTQIA+ represents a broad spectrum of identities, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual, as well as others who do not conform to traditional notions of gender and sexuality. This study includes individuals who are out or closeted, by looking at representation and understanding the lived experience of people in architecture who identify as anything other than heterosexual. In doing so, this study attempts to recognize being “out” as a radical act of self-revelation and resistance, referring to those who openly acknowledge their sexual orientation or gender identity, while also acknowledging that safety, personal, and political circumstances shape each person’s journey toward embracing and expressing their identity. For the purpose of this research, we are defining gender, sexuality, and LGBTQIA+ as follows.

- Gender – A set of socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that a given society considers appropriate related to a person’s sex assigned at birth.

- Gender Identity – A person’s internal sense of their own gender, which may align with or differ from a person’s sex assigned at birth.

- Sexuality – A person’s emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to others.

- Lesbian – A woman who is attracted to other women or sapphic people.

- Gay – A person, often a man, who is attracted to people of the same gender.

- Bisexual – A person attracted to more than one gender.

- Transgender – A person whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

- Queer – An umbrella term for non-heteronormative identities.

- Questioning – A person exploring their sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Intersex – A person born with physical sex characteristics that do not fit typical definitions of male or female.

- Asexual – A person who experiences little or no sexual attraction.

- Aromantic – A person who experiences little or no romantic attraction.

- Agender – A person who identifies as having no gender.

- Pansexual – A person who is attracted to others regardless of their gender identity or sex, emphasizing the fluidity of attraction.

- Non-binary – A person whose gender identity does not fit within the traditional categories of male or female, often encompassing a spectrum of genders outside the binary.

- Plus – A person who identifies with the multitude of other sexual orientations and identities not explicitly stated above.

Acknowledging the importance of this topic involves framing it from multiple points of view. On one hand, there is the need to recognize and celebrate the contributions of LGBTQIA+ individuals in architecture, emphasizing their role in driving innovation and creativity. On the other hand, it is crucial to address the challenges and systemic barriers they face. This research encompasses a multitude of intersections with queer identity, recognizing the pluralistic and dynamic nature of gender and sexuality. This dual perspective allows for a comprehensive understanding of the significance of queer representation in architecture.

Central to the mission of this research series is the importance of giving voice and space to people from backgrounds who have been historically discriminated against. ACSA is asking questions to help cultivate a better understanding of how the LGBTQIA+ communities impact the built environment. Where is the data on LGBTQIA+ people in architecture? How do people identifying as LGBTQIA+ navigate architectural design differently than straight people? How does gender and identity intersect with race for designers? How can the profession be more equitable? As always, let’s start with a brief history.

The history of LGBTQIA+ individuals in America is rich and complex, marked by significant milestones that have shaped the community’s social and legal standing. Indigenous people on this continent have recognized a wide range of sexualities for thousands of years before European colonization. Africans kidnapped and trafficked across the Atlantic into enslavement carried with them a diversity of gender expressions, whose legacies survive today in Afro-diasporic queer communities. The categories ‘straight’ and ‘gay’ as we know them today are products of Victorian-era Anglo-American culture, not naturally or biologically ordained. During Reconstruction, Frances Thompson, a Black trans woman born enslaved in Alabama, testified before Congress in defense of her Memphis community following an assault by violent ex-Confederates in 1866. In 1924, the Society for Human Rights was founded, representing the first known gay rights organization in the United States. This was followed by the landmark 1958 Supreme Court case One, Inc. v. Olesen, which granted free speech rights to a pro-gay publication. Often times LGBT history starts with the well-known 1969 Stonewall uprising in response to police harassment of Black and Latine, trans and gender nonconforming New Yorkers. Beyond Stonewall and the devastating AIDS pandemic that began in the 1980s, there have been numerous other pivotal moments. In 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize gay marriage, setting a precedent for nationwide legal recognition of same-sex unions. According to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), in recent years policymakers have created over 200 pieces of legislation targeting the rights of transgender people with access to medical care and use of public spaces. Moreover, the HRC reported that 2022 saw the highest number of anti-transgender hate crimes recorded by the FBI to date, with incidents increasing by more than 32% from the previous year. These touchpoints highlight the ongoing struggle for equality and the resilience of the LGBTQIA+ communities. Taken together, this history demonstrates that gender expansiveness is inherently anti-colonial.

Issues of equity in architecture related to the LGBTQIA+ population are multifaceted and deeply interconnected with broader social justice concerns. As it relates to architecture, housing is a critical area, as queer families and youth often face unique challenges, including homelessness and discriminatory housing policies. Research published by the Williams Institute, a think tank housed at UCLA Law, highlights the importance of communal living arrangements and shelters specifically designed to support LGBTQIA+ individuals. Additionally, social spaces fostering a sense of belonging for the most marginalized people are vital, as is the preservation of queer history and memory through community engagement, public art, and alternative forms of placemaking. This is why representation matters.

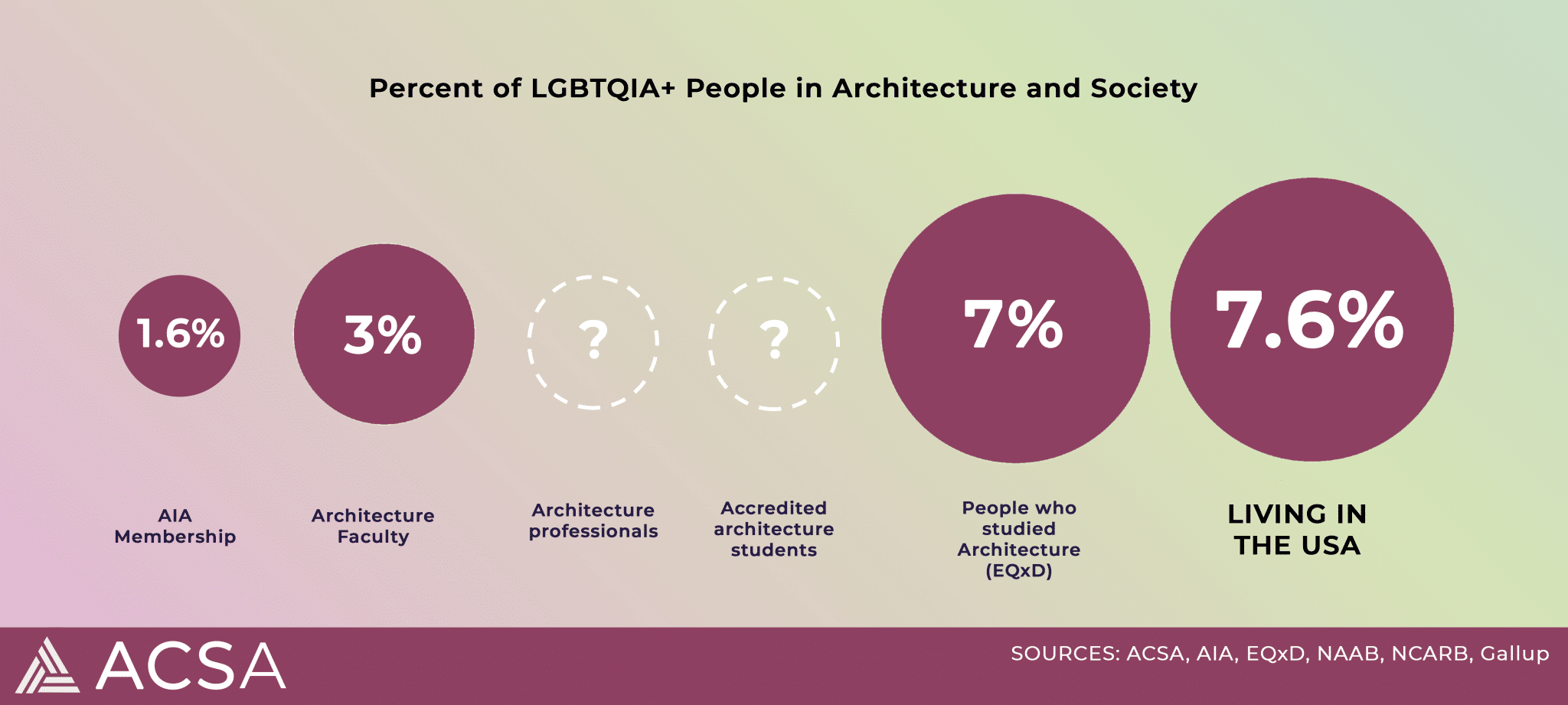

On the whole, data and statistics on the LGBTQIA+ population are lacking, a jeopardizing situation which plays straight into the narrative of citizens and policymakers who seek to erase queer people, and especially trans and gender nonconforming people, as recognized – much less protected – legal categories. On the national level, the U.S. Census has not yet implemented an accurate way of counting the percentage of LGBTQIA+ people in the United States. Their best estimate is based on same-sex households, reporting 1% of the households in the United States are composed of same sex married couples. When looking individually, the 2023 Gallup poll gives us an estimated 7.6% of the U.S. population as self-identifying as LGBTQ+ with the bisexual population making up more than half (57%) of the LGBTQ+ population.

In architecture, the 2018 Equity in Architecture survey conducted by AIA San Francisco with ACSA serving as a research partner, reported 7% of respondents identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) and the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) currently publish no data on LGBTQIA+ architects and designers. In 2023, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) reported nearly 2% of their membership self-identified as LGBTQIA+. Similarly, the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) reports that 3% of their faculty members self-identify as LGBTQIA+.

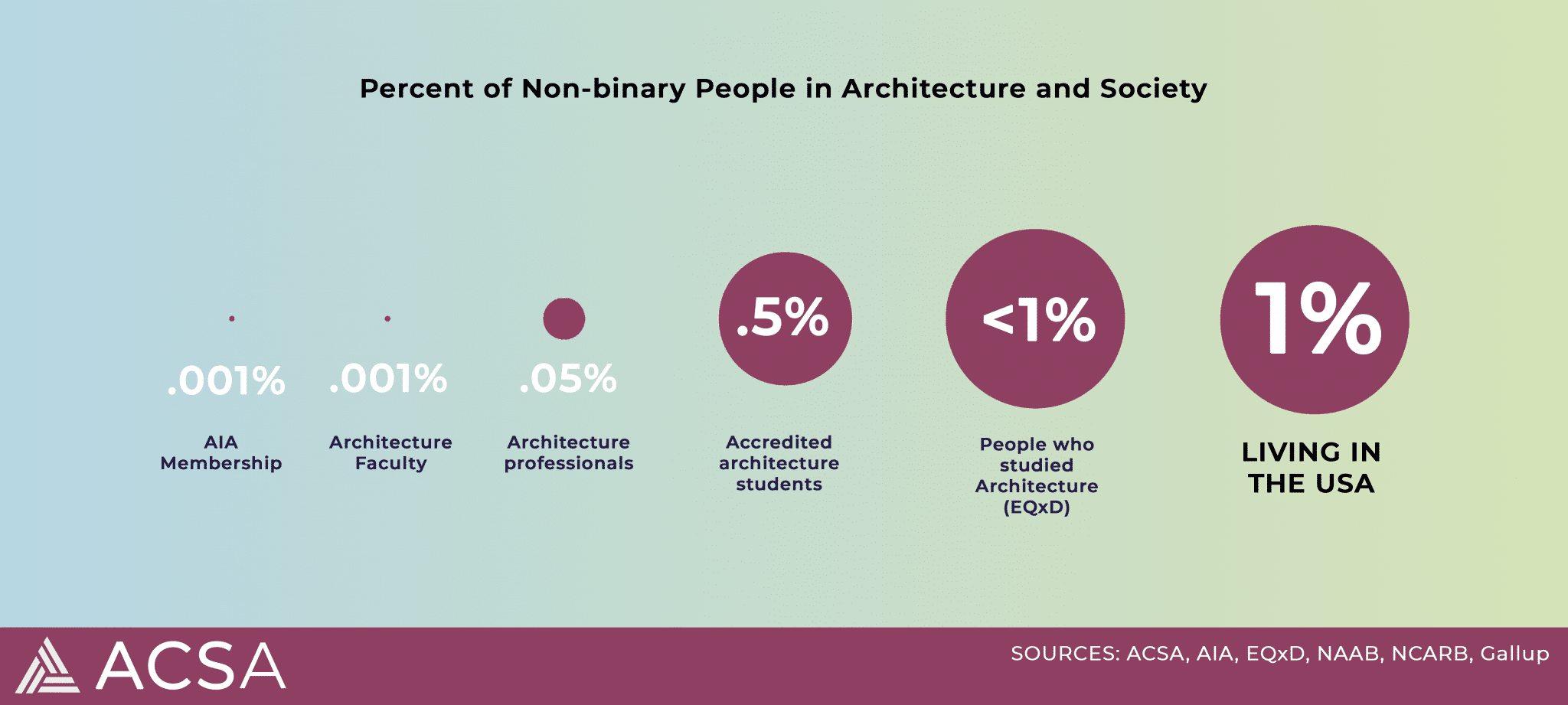

When we investigated the percentage of architects, designers, and educators identifying as non-binary, the statistics showed an even more significant disparity between the U.S. population and the architecture communities. The 2023 data from the Gallup poll reports 1% of the U.S. adult population identifies as non-binary, 80% of which also identify as LGBTQIA+. NCARB, AIA, and ACSA all report less than .05% of their respective record holders and members self-identified as non-binary. Much like the numbers reported for the LGBTQIA+ community, the 2018 Equity in Architecture survey reported a non-binary respondent population of just under 1%, more closely matching the estimated total U.S. population statistic.

Between quantitative and qualitative data rests an interpretation of the challenges of an identity that must be claimed or pronounced in a public sphere. What metrics can be used to measure the silence of those who choose not to report their identity anywhere on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum? What creates and comes from the absence of critical intersections from the data?

Queer poet and activist Audre Lorde reflects on “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” and diagnoses the reverberating void of speech as such: “In the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear — fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgment, or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation.” Put simply, visibility for queer populations, especially transgender people of color, has come with a risk of rejection or violence for generations. The impetus then is not on the identifying individual, but rather the society that they inhabit to shift paradigms to make room for bodies outside of what is considered the norm.

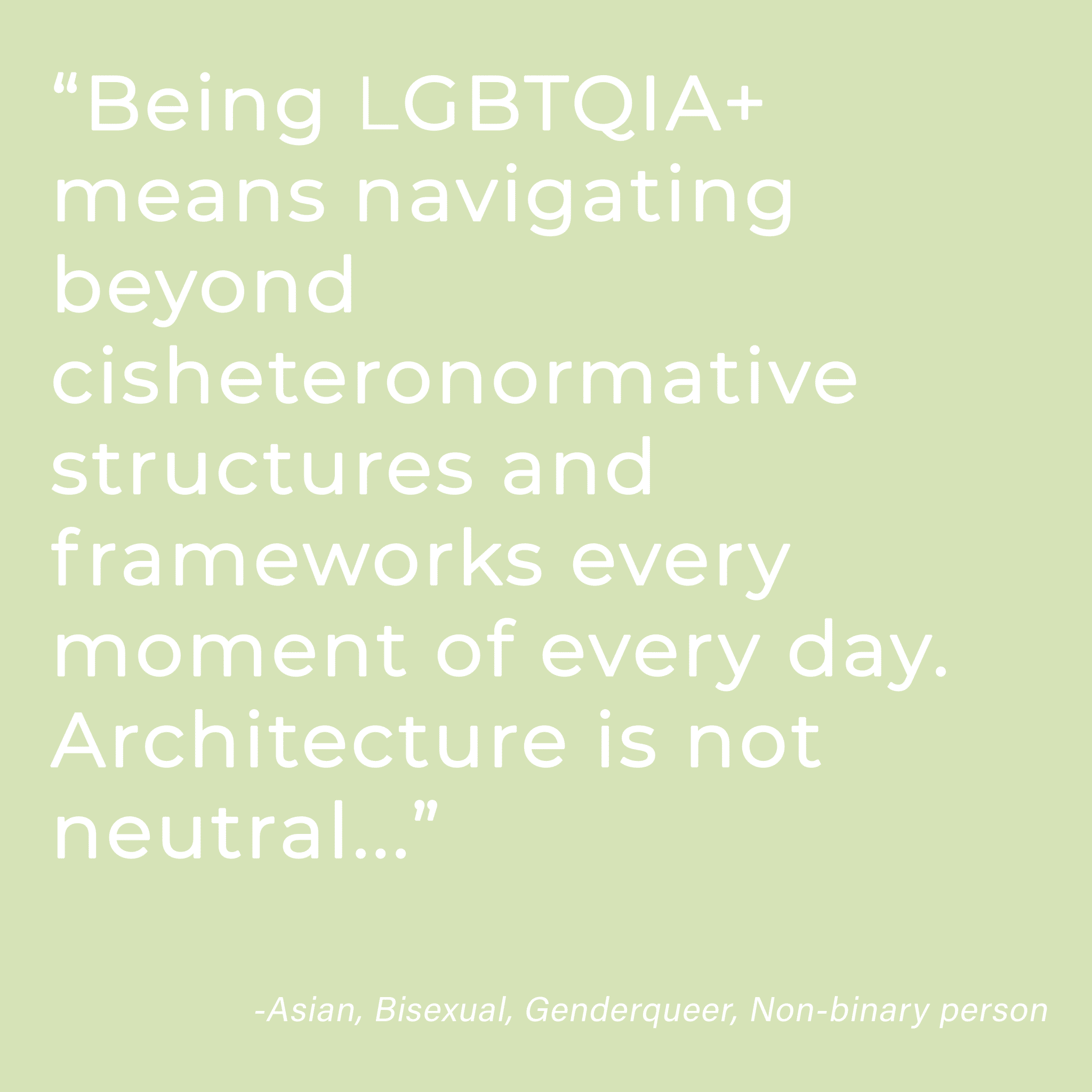

In both practice and the academy, architects and designers play a key role in naturalizing binaries in the built environment, from bathrooms to housing to campuses and landscapes. Our concepts of space assert realities that often fail to serve, let alone recognize, the body beyond the binary.

Even with limited responses in this survey, the qualitative data trends towards a desire to challenge the status quo and serve a broader polity beyond the binary. Giving agency to populations who identify on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum to influence the profession expands an understanding of who the public we serve is, because queer communities are expansive in nature, connecting across race, ethnicity, ability, and generations.

The presentation of this data serves as a benchmark for comparison in the future. We will keep the survey open for respondents to participate, allowing us to continue gathering additional data. As new information becomes available, we will explore opportunities to update and enhance the research findings accordingly. We invite LGBTQIA+ readers to use the link below if they missed the initial call to participate, and to share widely with other LGBTQIA+ people in architecture.

As previously mentioned, the LGBTQIA+ community is extraordinarily diverse. ACSA recruited a convenience sample of architects, designers, and educators to accurately communicate people’s lived experiences across the discipline. Compared to race and other identities, gender and sexuality are based more on internal assessments than external perceptions and for this reason are more fluid. The experiences of individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender are quite varied as they intersect with race, ability, socioeconomic status and the like. The qualitative research below uncovered the importance of inclusive spaces, challenging the status quo, and the need for more discussion around architecture’s political power.

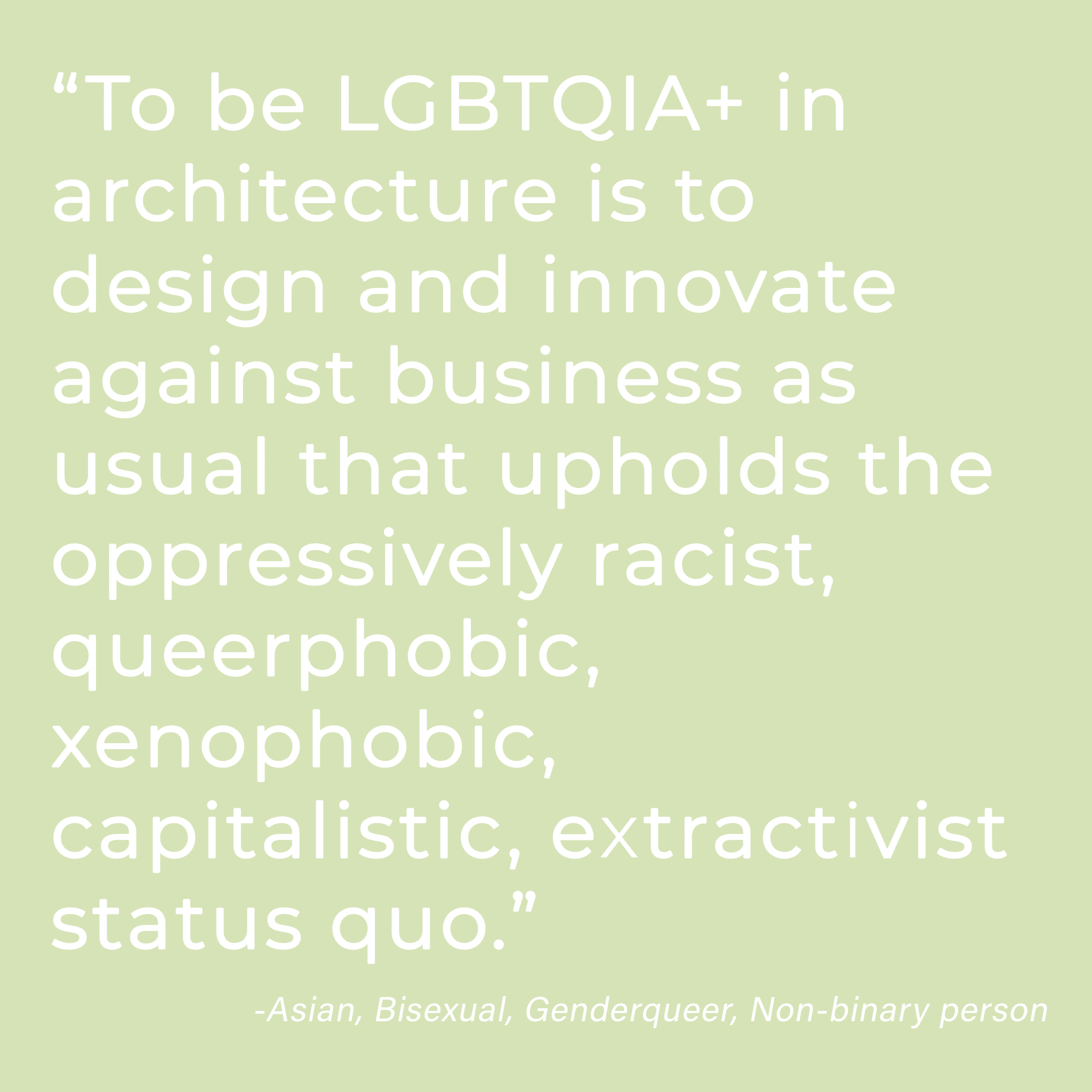

When we asked survey participants what it means to be LGBTQIA+ in architecture, many cited an increased awareness or sensibility about what it means to be marginalized. However, the most frequent themes that emerged were challenging norms. This manifested as a way of working that is explicitly counter to the status quo.

In addition to challenging norms and stereotypes, many respondents noted their respective positions towards inclusive spaces. Despite the differences in the ways they identified, generally responses carried a throughline of advocating for atypical space making.

Another theme emerging from the research was an explicit advocacy for queerness and queer spaces. While most respondents acknowledged that inclusive spaces were better for all people, some respondents conveyed a more distinguished sense of knowledge and activism around spaces of conflict for the LGBTQIA+ community.

To gain a fuller understanding of the LGBTQIA+ community, we took a deeper dive into the multitude of identities queer people hold. These intersections with race, gender, class, religion, etc. not only mediate the way respondents are seen in the world but also mediate their perspectives as they relate to architecture. This is not unlike any other marginalized group. When we asked survey participants about how the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality expand the boundaries of architecture, the most frequent response dealt with expanding the ways architecture responds to people. At its core, it’s about seeing and being seen. It’s about resisting the prevailing narrative around who architecture is supposed to serve and asking questions that provoke change.

Lastly, we asked participants about what was missing from mainstream discourse about architecture. Respondents overwhelmingly cited architecture and its political power. While many acknowledged the ability for the built environment to disenfranchise, responses carried connections surrounding what architecture could be. Said differently, architects and designers were motivated to center discussions around the role of the built environment in capitalism and exclusion, so that the discipline could rectify past harms for a more just future.

To read more on the intersections between queerness and architecture read the essay “Beyond Binaries,” part II of Where Are My People? Queer in Architecture.

Questions

This research was conducted in collaboration with Emergent Grounds for Design Education.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL