Barbara Opar and Lucy Campbell, column editors

Column by Maya Gervits, Director of the Barbara & Leonard Littman Library, College of Architecture & Design, New Jersey Institute of Technology

According to a recent Andrew Mellon Foundation report, many academic institutions are now investigating partnerships between the arts and other academic disciplines to foster connections between them [1]. During these discussions, music has received special attention. It has been proven that musical compositions can inspire higher brain functioning and unlock creativity [2]. Albert Einstein, who credited some of his discoveries to musical perception, believed that music is the driving force behind intuition. Links between music and spatial-temporal skills, those important in solving problems, have been discovered by neuroscientists. Mozart and Vivaldi effects [3] are discussed in scientific journals. There are many associations to be found between music and architecture, music and visual arts, and design. They have been discussed over the centuries and were part of the reasoning behind the Littman Library’s attempt to engage students in the College of Architecture and Design at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in further exploration of these connections by hosting musical events.

The relationship between architecture and music is well documented. Leon Battista Alberti believed that the same characteristics that please the eye also please the ear. Palladio echoed this by noticing that, “the proportions of the voices are harmonies for the ears; those of the measurements are harmonies for the eyes. Such harmonies usually please very much without anyone knowing why, excepting the student of the causality of things”. [4] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called architecture the “frozen music,” while 19th century art critic Walter Pater came to the conclusion that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” We discuss rhythm, proportion, and ornamentation in both music and visual arts, and search for harmony between them.

Typically associated with German Romantics, the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk described as a complete, unified, or as it often referred to, a “total work of art”, was formulated in 1849 in Richard Wagner’s “Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft“ ( “The Artwork of the Future” ). Although, Hans Sedlmayr insisted that it existed long before that time [5]. Initially related to the synthesis of arts in opera, it also has been manifested in Charles Baudelaire and

Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry, Josef Hoffmann’s and Joseph Maria Olbrich’s architecture, James McNeil Whistler’s paintings, Sergei Diagilev’s ballet, and Alexander Skriabin’s musical compositions. The 20th century provided more tools to rethink the boundaries between the visual and musical. Creation of the “total work of art” was the ultimate goal of the Bauhaus program and the cornerstone of their educational system. Oscar Schlemmer’s “Triadisches Ballett” and Wassily Kandinsky’s experimental performances, rooted in his synesthesia (ability to see sounds), are just two of several Bauhaus projects created as an interplay of music, dance, and painting. “Poème électronique” and “Philips Pavilion” at Expo 58 – collaborative works by Edgard Varèse, Le Corbusier, and Iannis Xenakis, which combined electronic music, projections, and architecture, also came into existence with the purpose of creating a “total work of art.”

Although open to the whole

[1] https://mellon.org/about/annual-reports/2014-presidents-report/#higher-education

[2] E. Glenn Schellenberg Music and Cognitive Abilities in Current Directions in Psychological Science, v.14,n.6,2005.p317-320; R. Root-Bernstein Music, Creativity and Scientific Thinking Leonardo, v.34,n.1,2001,pp63-68

[3] K.Nantais and G.Schellenberg The Mozart Effect: an artifact of Preference. Psychological Science, July 1999.v.10,n4,pp370-373; L.Riby The joys of spring: Changes in Mental Alertness and brain functions Experimental psychology, vol. 60, 2013,p.71-79.

[4] M. Trachtenberg ”Architecture and Music Reunited: a New Reading of Dufay’s Nuper Rosarum Flores and the Cathedral of Florence” in Renaissance Quarterly, is.54,2001,p, 740.

[5] Hans Sedlmayr Der Verlust der Mitte: Die bildende Kunst des 19 und 20 Jahrhunderts als Symptoms und Symbol der Zeit. Frankfurt am Mein, 1985.

[6] .Hans Ulrich Reck Immersive environment: the Gesamtkunstwerk of the 21st century? At: http://www.khm.de/kmw/reck/essays-ecrits-writings-saggi-ensayos/english/immersive-environments-the-gesamtkunstwerk-of-the-21-century/

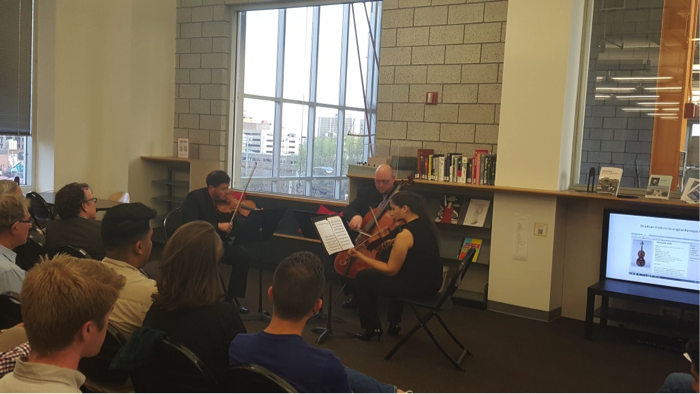

[7] Montclair trio – Robert Radliff, Aurora Mendez and Paul Vanderwall

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL