Article submitted by Jesse Vestermark, Architecture and Environmental Design Librarian, California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo

Barbara Opar and Barret Havens, column editors

Editor’s note: The article which follows discusses a challenging situation for faculty in the design disciplines and librarians alike: how to gear students in large introductory classes up for doing college-level research during a brief, one-time library instruction session. Our colleague Jesse Vestermark shares some strategies for maximizing the impact of these “one-shot” scenarios.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have received a lot of attention in the last few years, but what about large, in-person “one-shot” sessions? These are instructional scenarios where a professional–in our case, librarian–is given the one-time opportunity to address a large introductory course. Obviously, the larger the course, the more students a librarian can reach in one fell swoop, so there is much to be gained by carefully planning for the greatest impact.

As the librarian for the College of Architecture and Environmental Design at California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo, I have become something of a trial-by-fire veteran of this scenario, co-designing the course’s research assignments for our pass/fail Introduction to Environmental Design (EDES 101) course, which has ballooned from 300 students in 2011 to over 400 last fall. Each year a different professor has taught the course and driven the assignment’s primary content, while I steered it in a direction that would provide a foundation for research fundamentals.

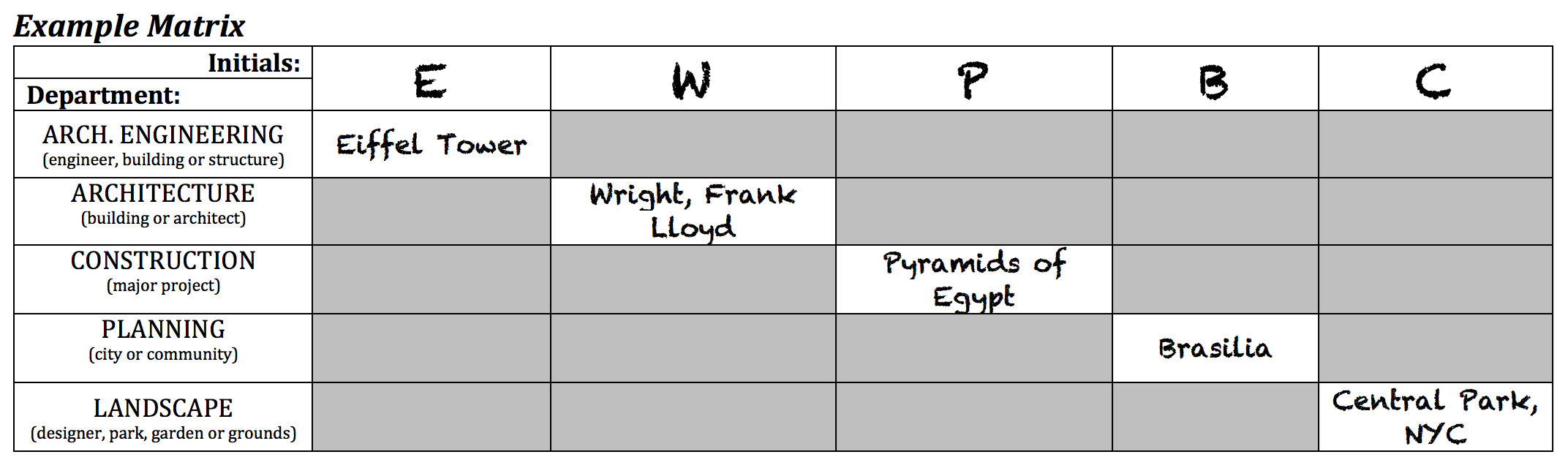

The first year, we devised what was easily the most complicated assignment, yet ironically towards the simplest end: to find a single book in the library on the topic of their interest. However, for fear of bottlenecking on certain topics, authors, architects or books, the professor suggested a clever matrix puzzle for groups of 5 to solve by limiting their topic to a combination of discipline and first initial.

Example of a completed matrix puzzle using randomly chosen initials. Concept by Thomas Jones.

Once they identified a book on their topic, they weren’t required to check it out–simply photograph it sitting in the stacks. This made for an easy deliverable, but explaining the concept behind the matrix and shepherding 300 students into groups of five required a lot of work for the simple outcome of familiarizing them with the library’s organization.

In 2012, we went interactive, focused more on critical thinking, and expanded my participation to two class meetings, giving us the opportunity to expand in depth. The first time I addressed the students, we covered the nuts and bolts of our discovery system–the recent makeover of our catalog that allowed them to find books and articles. They were again allowed to pick their topic, but instead of a photo of a single book in the stacks, the professor had them find and cite nine sources: three books, three articles, and three websites.

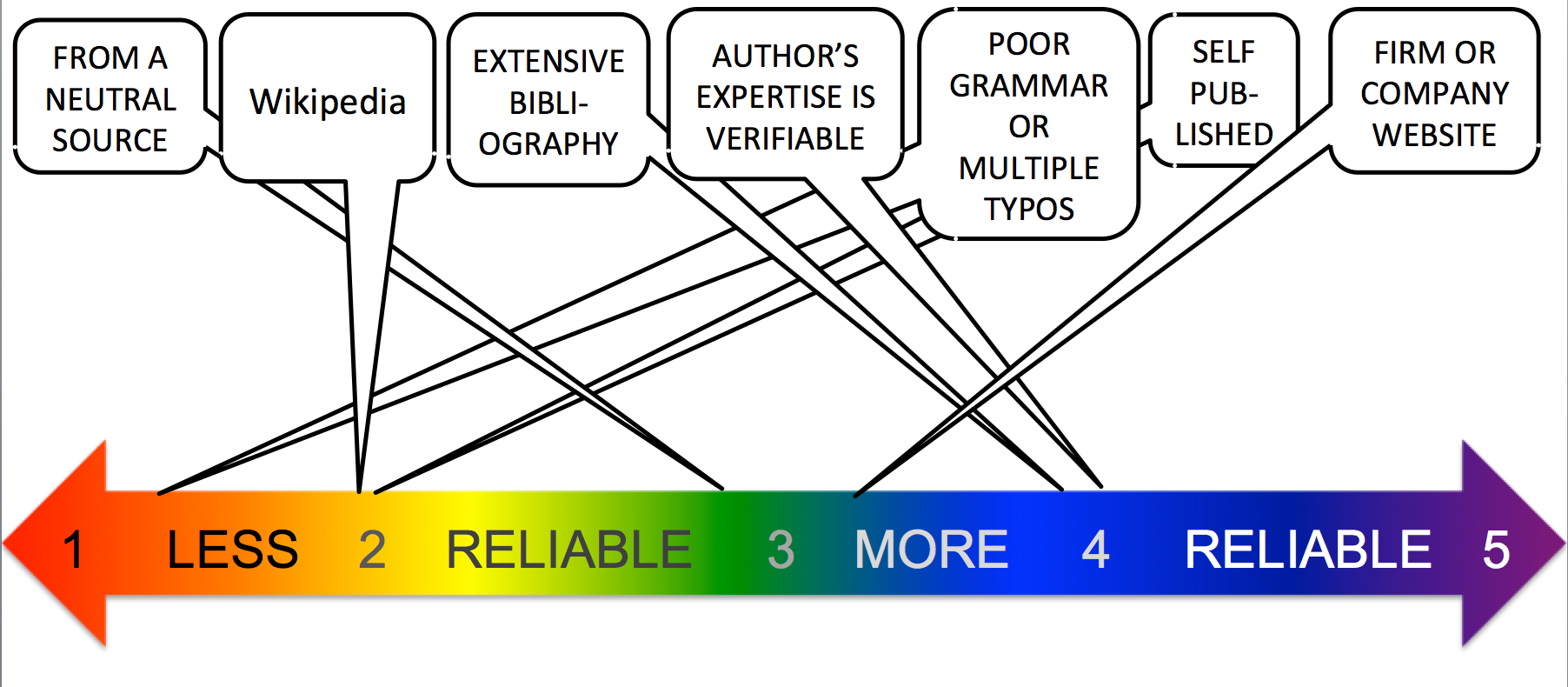

The instructor had also required the students to purchase remote voting devices commonly called “clickers” to allow the students to weigh in, multiple-choice-style, on class topics. For the second session, students were asked use the clickers to rate various types of sources or source characteristics on a “spectrum of reliability” both in their own experience and along with a librarian/professor “live” discussion of academic resources such as trade articles, peer-reviewed articles and architecture firm websites. This was a crucial step towards imparting the lifelong skill of critically evaluating information sources.

Visual representation of the results of the “spectrum of reliability” interactive exercise.

Last year, with a third completely different assignment, we were able to ramp up the depth of real-world source evaluation even as I was again limited to one class visit. This time, students were asked to role-play and engage as a team in local mock-planning projects, representing either the city, the public, expert consultants or the design team. I took the opportunity to focus most of the hour on explaining the clues, characteristics of and differences between the range of reliable sources their role-playing might lead them to encounter, including academic, professional, government documents as well as free information found via search engines. For example, the city might look at the general plans of other, similar cities, consultants may study more of the peer-reviewed literature, the public might start with free, web-based information and the design team may look at a little of everything. I incorporated diagrams and images to illustrate universal concepts such as “stakes” and “biases” as they relate to the professions. To illustrate stakes, I compiled the images on an “information timeline” using photos to illustrate that immediate Google results are adequate for settling pop culture debates but as the responsibilities and consequences of one’s professional life increase, so should the quality of the resources one consults. For biases, I used the classic blind men and the elephant story.

Digitized version of original woodcut print “Blind Monks Examining an Elephant” by Hanabusa Itch_ available from the Library of Congress with “no known restrictions on publication in the U.S.”

We even examined the fine print of Wikipedia’s “Identifying reliable sources” page, which generalizes that the higher the degree of scrutiny, the more reliable a source is likely to be.

Instead of having the students use clickers to vote on the relative reliability of potential sources, I used mobile polling software, PollEverywhere, for which our library subscribes to a single higher-ed account that allows up to 400 respondents and instructor moderation. Using PollEverywhere, I essentially gave them a three-question pretest and posttest assessment on appropriate source choices for different research scenarios. I gave the students one of ten source choices, and the scenarios varied from seeking an at-a-glance overview on a topic to needing information that had been reviewed by experts. The results suggest they listened and took my professional advice to heart. For example, when asked the “best place to get detailed information that has been subject to expert editorial review” and given ten options, only about 35% of the 243 respondents chose “peer-reviewed publications” the first time around. When asked the same question at the end of the class, exactly two-thirds of the 159 respondents chose “peer-reviewed publications.”

PRE-LECTURE:

POST-LECTURE:

Note from the reduced number of respondents that I found that when you request voluntary participation, their interest in voting wanes over the course of an early-morning hour.

Some of the keys to success in the evolution of these collaborative lessons were pretty straightforward, but not necessarily easy to execute with little face-to-face time and lots of students. My primary advice is to plan ahead, collaborate, simplify, be flexible, interact with the audience, visualize, and practicalize. I would also encourage a combination of humor, passion and variety while maintaining your professionality. We all have strengths and weaknesses on those fronts, but above all, I’ve found that if I treat the material with earnestness, the students respond in kind.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL