Sept. 29 – Oct. 1, 2021 | Virtual Conference

2021 AIA/ACSA Intersections Research Conference: COMMUNITIES

Fall Conference

Schedule

May 19, 2021

Abstract Deadline

July 2021

Abstract Notification

Sept. 29 – Oct. 1, 2021

Virtual Conference

Schedule + Abstracts: Wednesday

Following is the conference schedule, which is subject to change. This year’s AIA/ACSA Intersections Research Conference will be held virtually from September 29 – October 1, 2021.

Schedule with Abstracts

Below read full session descriptions and research abstracts. Plan what session you don’t want to miss.

Obtain Continuing Education Credits (CES) / Learning Units (LU), including Health, Safety and Welfare (HSW). Registered conference attendees will be able to submit sessions attended for Continuing Education Credits (CES). Register for the conference today to gain access to all the AIA/CES credit sessions.

11:00 – 12:00 EDT /

08:00 – 09:00 PDT

Plenary

1 HSW Credit

CONFERENCE WELCOME:

Peter Exley

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

AIA President

Georgeen Theodore

New Jersey Institute of Technology

Conference Co-Chair

Rico Quirindongo

City of Seattle, Office of Planning and Community Development

Conference Co-Chair

Interview with Jelani Cobb

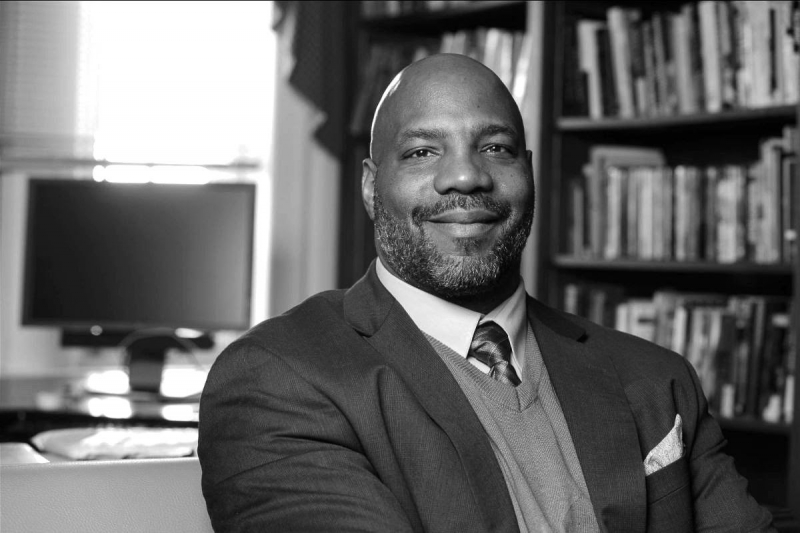

JELANI COBB

Columbia University & The New Yorker

Bio

Jelani Cobb

Columbia University & The New Yorker

Jelani Cobb, Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Professor of Journalism and a long-time staff writer at The New Yorker. The conference will examine the legacy of our built environment and its communal implications. Cobb’s writings on race, history, justice, and politics earned him the 2015 Hillman Prize for opinion and analysis journalism. He is the author of Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress, To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic, and The Devil & Dave Chappelle and Other Essays.

30-minute

Coffee Break

12:30 – 14:00 EDT /

09:30 – 11:00 PDT

Research Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Equitable Communities

Session I

Moderator: Marshall Brown, Princeton University

The Democratic Future of Virtual Public Consultation: Interdisciplinary Research During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Shelby Hagerman, Carleton University

Zach Colbert, Carleton University

Daniel Dickson, Carleton University

Abstract

The COVID-19 Pandemic has significantly affected design practice and research workflows, surfacing an opportunity to reveal and confront expansive questions concerning equity and resilience. Meanwhile, the modes for engaging a concerned public in these matters have encountered substantial challenges. In the Euro-American context, community-led design and participatory sessions, first established in the 1970s, are broadly integrated into the process of building. Academic research typically mirrors such participatory sessions by conducting interviews, design charrettes and focus groups. These conventional methods have proven inadequate amidst social distancing protocols, exacerbating the challenge to reach disparate populations towards a truly representative audience. Architectural practice must seek new, empowering virtual forms to ensure effective, equitable engagement.

A primary concern about public consultation sessions is that they can be fraught with theatrics, creating an illusion of community participation to carefully obfuscate predetermined outcomes. These sessions tend to contention, placing the developer of a project—frequently entwined with city planning officials—in an adversarial and hierarchical position above community participants. As Shannon Mattern describes in her critique of The Sidewalk Toronto Project, “‘Participation’ is now deployed as part of a public performance wherein the aesthetics of collaboration signify democratic process, without always providing the real thing. A disingenuous use of maps, apps, and other tools of participatory planning—call it mapwashing—threatens to undermine the democratizing, even radical potential of civic design.” Essentially, public consultation sessions have been used as a superficial tool, enabling projects to appear approachable, transparent, and amenable to public concern while failing to genuinely incorporate community feedback into the design process.

Such practices are challenged by virtual platforms that have been adopted to conduct innovative forms of public consultation during the pandemic. Virtual meeting applications (Zoom) and digital collaborative workspaces (Figma and Miro) have become engrained in designers’ daily workflows. The authors of this work are members of an interdisciplinary research team investigating the implementation of a gravity turbine in multi-family building wastewater systems from public policy, mechanical engineering, and architectural perspectives. In the past year, the team has transitioned their approach to interviews, adapting design charrettes and focus groups—originally intended to be traditional in-person meetings—onto the aforementioned virtual platforms. The goal of these public consultation sessions is to gain insights and additional design constraints that may not have been anticipated. Despite facing complications such as a more condensed timeframe for sessions as well as an increased complexity to access and engage in interactive material, Zoom has become a democratic space where all meeting participants are on an equal footing with an identical view of content shared on Miro and Figma. The platforms are versatile and adaptable to accommodate different participant groups. The authors draw on findings they continue to gain from ongoing sessions, discussing the shortcomings and opportunities that virtual public consultation allows. It is suspected that certain methodologies and approaches learned will persist through the post-pandemic world, and this paper explores the democratizing potential of public consultation through virtual mediums.

Dalsgaard, Peter. “Participatory Design in Large-Scale Public Projects: Challenges and Opportunities.” Design Issues 28, no. 3 (July 2012): 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00160.

Lennertz, W. R., Lutzenhiser, A., & Duany, A. (2014). The charrette handbook: the essential guide to design-based public involvement. American Planning Association.

Mattern, Shannon . “Post-It Note City,” Places Journal, February 2020. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/200211

Home/Financing: Geographies of Real Estate Speculation

Dare Brawley, Columbia University

Abstract

The acquisition of distressed and real estate owned properties since 2008 by LLCs was explicitly supported by the Federal Housing Finance Agency and was assumed to be a stabilizing force.1 However in the years since, research has uncovered many ways in which investor-ownership has been destabilizing for housing markets, served to transfer wealth out of communities of color, and has contributed to increasing rates of eviction.2,3,4 Invitation Homes is the singular illustration of the expansion of SFR holdings. Since the great recession it has become the nation’s largest landlord of single-family houses owning over 80,000 homes nationwide – and it is a bellwether for the industry more broadly. During the summer of 2020, Invitation Homes raised nearly $450 million to potentially double the number of houses they control in anticipation of large numbers of distressed properties as a result of COVID-19.5 Other Real Estate Investment Trusts and LLC managers are reportedly doing the same.6

Aiming to contribute to emerging work on the actions and impacts of non-occupant investors in housing, this paper presents ongoing research into three cities in the northeastern United States. In Philadelphia, Newark, and Rochester the project traces new geographies of real estate purchases made specifically by investors who do not intend to live in the homes they are buying. Using public data and geographic information systems (GIS) methods the project uncovers how houses purchased as investment vehicles between 2000-2020 have been concentrated spatially, then compares these patterns with the geography of houses that have been purchased as homes.

Though still ongoing, preliminary outcomes of this research suggest that the geographies of investor and owner-occupant purchases are largely distinct – that investor ownership is fueling a separate housing geography and is not merely a part of the overall housing market. These patterns suggest that certain neighborhoods are targeted as sites for outside investment (and thus either rent extraction or real estate speculation) and not for sustainable affordable housing (or community wealth generation).

For architects, designers, and planners working in these contexts the research suggests a new urgency for ensuring that neighborhood investment is carried out in ways that structurally support equitable communities. It asks that we consider the ways in which our disciplines have been complicit in perpetuating investment mechanisms designed to produce accumulation through dispossession, and in turn speculates on possibilities for more just urban futures.

Studio Progress Report: An Infrastructure for Restorative Justice

Darrick Borowski, School of Visual Arts, NYC

Rik Ekstrom, School of Visual Arts, NYC

Abstract

In the fall of 2019 New York’s City Council approved plans to close Rikers Island, one of the world’s largest and most notorious jails. The decision was a result of a long-fought, still ongoing, battle to push the city toward reckoning with an unjust, and demonstrably racist, mass incarceration system. The city settled on a plan to replace the remote island complex with four “borough-based” jails. The new jails, the city said, will adopt the newest best practices, particularly more progressive northern European models, and be “safer, smaller and more humane”. Our team was invited by the NYC Dept of Design and Construction to contribute to the research that will inform these new institutions. But the year that followed reinforced our hypothesis that “better prisons” are not enough.

2020 saw Black Lives Matter protests erupt around the world. Quarantined citizens were moved to march by the killings of George Flloyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Jacob Blake, and more, at the hands of police. As educators, training future designers of the built environment, this research team set out to go deeper, to investigate how we might leverage our cities—our streets, sidewalks, buildings, and public places—to end mass incarceration, while promoting equity and beginning the process of healing in communities disproportionately affected by the carceral system. We frame this project as an urgent infrastructure project, An Infrastructure for Restorative Justice.

In this paper we lay out learnings from the first two years of this ongoing, student-run study to develop a bottom-up, community-based approach to ending mass incarceration.

The initial studio brought us to two overarching conclusions. The first is an approach to and scope for programming, which we summarize as being captured by five “touchpoints”—Advocacy, Prevention, Intervention, Mitigation, Re-entry. The second is the spatialization of these programs which, we propose, need to be woven into the urban/neighborhood fabric at various scales and positions in the public realm.

This past year’s studio built on the framework developed in the first, by linking up with organizations at the forefront of criminal justice reform to apply our framework to real projects, real sites, and real communities. Along with NYC DDC, the studio has partnered with the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, the Center for Court Innovation, and the VERA Institute of Justice to explore opportunities for practical interventions. The resulting projects ranged in scope and scale from mobile, street-based installations to new Community Justice Centers in Far Rockaway and Queensbridge, and propositions for a redesigned Bronx Housing Court, including a new Problem Solving Court

In documenting and sharing this work, we aim to provoke our colleagues in academia, to encourage a new generation of designers to exercise their agency and criticality, and use their work to advance social change.

12:30 – 14:00 EDT /

09:30 – 11:00 PDT

Research Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Equitable Communities

Session II

Moderator: Virginia Stanard, University of Detroit Mercy

Abandonment – Education: Decentralizing education through adapt and reuse

Dylan Roth, Louisiana State University

Abstract

Architecture as a result of the systems of patronage and consumerism is in need of alternative conversations—these dialogues must take a multiscalar, hegemonic approach to systems of power within underserved communities. Abandonment to Education is a call to acknowledge the consequences of neglect and imbalance, a petition for the need for reciprocity and socialization. Through adaptation and reuse of the existing fabric, the project reimages social justice, sustenance, and equity by dismantling existing informal barriers. Within the proposal, abandonment takes a new life—a new educational hub consisting of alternative programming—while simultaneously creating a network of interconnected bike and pedestrian pathways. Abandonment to Education aims to address the obstacles that are linked to mental and health issues, local employment, and equity within BIPOC communities.

Baton Rouge contains a long history of racial segregation that has materialized in into extreme disparities among divided communities within the city. Today, Baton Rouge is recognized as one of the most racially segregated cities where the majority of the BIPOC population has been systematically contained to the north, with little to no economic opportunity for its citizens – leaving many to live in extreme poverty with limited social mobility, while the south is majority white with continuous economic development, opportunities for better schools, healthcare, and overall mental, physical, and social wellbeing.

The project began by attempting to map racial separation; to represent the divisions within the city by creating a timeline that observes the correlation between the shift in demographics and significant political and economic histories. The research outlines disparities through a series of maps and diagrams that speak across 4 decades: 1980, 2000, 2010, and 2018. The data reveals the influence of policy within the racial restructuring of school zones and economic opportunity—a visual tale of systematic oppression.

Along with urban decay, the exodus of white populations from the city of Baton Rouge has left its public schools in shambles as tax revenue is continuously cut from overall program funding. Abandonment to Education reclaims abandoned buildings along previously bustling business corridors and repurposes them into an urban educational hub that has the capacity to continuously adapt to the needs of the local community. To develop the project programming was chosen strategically to help address existing sociological/psychological issues that are a result of children growing up in systematic oppression. The programs expand beyond the CORE curriculum offered in the East Baton Rouge Public school system. These include activities that help young adults manage anxieties and frustrations that they face on a daily basis through physical, mental, and creative expression. The project exists not as a cohesive linear thought but is imagined as a continuous development that progresses organically and adjusts depending on the immediate needs and desires of the community and children. It looks to address the severe inequality found within the East Baton Rouge school system by developing a new framework for education through the decentralization of the existing system of learning which has allowed for systematic segregation.

Black Bottom Street View: mobilizing a city archive

Emily Kutil, Lawrence Technological University

Abstract

This session will discuss Black Bottom Street View, an immersive representation of a historic African American neighborhood in Detroit that was razed during Urban Renewal. The Black Bottom Street View exhibit visualizes, spatializes and mobilizes a city archive in order to amplify ongoing efforts to preserve Black Bottom’s legacy.

The exhibit recreates Black Bottom’s street grid and envelops visitors within panoramic views constructed from stitched archival photographs of the neighborhood. The exhibit’s lightweight, tensile structure deploys at cultural events and local organizations across the city. The project collaborates to collect oral histories and other artifacts that tell Black Bottom stories from the perspective of its former residents.

Context

As Detroit’s population grew exponentially between the 1920s–1950s, the city’s housing crisis escalated. Racial violence, restrictive covenants, and federal redlining policies all limited the areas where African American families could live. In this context, Black Bottom became an African American economic and cultural hub with densely interconnected businesses, institutions, and residences: the center of African American life in Detroit.

When the Housing Act of 1949 and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided federal funding to local governments for “slum clearance” projects, cities across the United States used these funds to displace and demolish low income communities and communities of color. Over twenty-five years, Detroit demolished all of Black Bottom—almost a full square mile—and replaced it with I-375, Lafayette Park, and other Urban Renewal developments. The neighborhood’s residents were displaced; its institutions and businesses were forced to move or close.

The legacy of Black Bottom and the violence of its destruction echo through the city and the lives of its former residents and their communities. These histories are not contained within the past but are enmeshed in ongoing conversations concerning racial equity and community benefits in Detroit’s contemporary development.

Archive

The city produced over 2,000 photographs of Black Bottom during the eminent domain process. Now held by the Burton Historical Collection at the Detroit Public Library, the photographs were never intended to preserve images the neighborhood; today they have become a powerful record of its people and spaces.

Black Bottom Street View recomposes the photographs to present a panoramic snapshot of life in Black Bottom before the neighborhood was destroyed. The panoramas belie the city’s narrative that Black Bottom was a slum that wasn’t worth saving, showing instead a dense community with vibrant public life and unique urban form. By stitching and spatializing the archive, the exhibit bridges the historical digital collection and the contemporary physical world: the spaces, geographies and social events that make up the city.

Relationships

Black Bottom Street View aims to support and amplify the people and organizations who have worked to preserve Black Bottom’s history for decades. Local historians, writers, former residents and cultural organizations helped to develop and guide the project. Since 2019, Black Bottom Street View has joined with Black Bottom Archives to support a youth internship program and an interactive digital archive that connects the project’s maps and panoramas to oral histories.

Equitable Access to Building Construction Through Advancements in Global Building Machine Technology

Elizabeth Andrzejewski, Marywood University

Marcus Shaffer, Pennsylvania State University

Esther Obonyo, Pennsylvania State University

Abstract

On December 26th 2019, as the United Nations called for the “Implementation of the Right to Adequate Housing”, they attributed our global housing crisis to unequal access to housing, a dilemma caused by socioeconomic inequality rather than access to building materials. Currently, 1 billion people reside in informal settlements and more than 1.8 billion people globally lack adequate housing[i]. This problem of unequal access means that people are unable to secure adequate housing simply because they cannot afford to participate in the techno-economic structures of housing.

In recent history, society has turned to industrialized prefabricated housing as a source for economical, fast, and durable housing. While the Quonset Hut, Packaged House System, and the contemporary Better Shelter exemplify systems used during times of need, prefabrication as process needs to be re-examined in the context of today’s housing crisis. This paper examines these industrialized precedents toward articulating new solutions to housing. For example, the Packaged House System, developed by architects Konrad Wachsmann and Walter Gropius in 1939, differs from the other two precedents in that it was conceived as a universal prefabricated system. Though Konrad Wachsmann developed many universal systems, Wachsmann’s work was not intended to bring accessible housing to the masses, but rather provide housing that exhibited high quality achieved through industrial processes – houses that were flexible, adaptable, mobile, and easy to assemble and dissemble. Similarly, our contemporary crisis may demand solutions that include access to house-building as a process, methods of production traditionally controlled by construction industries. In an age where DIY culture and Open information are disrupting traditional structures of industrialized production, can the distribution of house-building technologies provide housing solutions to those in need?

Proposed here is a model of a universal building machine (UBM) and an agenda for housing solutions driven by Open-Source building technologies. This UBM is an architectural machine capable of processing material, handling material, fabricating building components, and assembling these components. This machine is informed by universal principles of Konrad Wachsmann’s prefabricated systems and his 7-axis Location Orientation Manipulator (L.O.M.), developed with PhD students John Bollinger and Xaiver Mendoza. A UBM informed by Wachsmann’s principles, and current technological advancements, could deliver affordable housing by essentially putting a mobile production machine on site. While industrial-scale housing production is inaccessible to the masses due to cost, Open technological solutions assembled from standardized parts and distributed through Open-source frameworks could realistically give people access to building technologies – a concept associated with distributed building machines such as the CINVA-RAM. By promoting accessibility to advanced building technologies developed and designed to be distributed to people in need, we empower individuals to actively and appropriately participate in the construction and maintenance of their own sustainable homes.

The Theater of the People: A look into Queens Street Vending Culture

Pedro Cruz, City College of New York

Abstract

At Corona Plaza, a proliferation of street vendors has gradually increased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Sellers of food, knickknacks, greens, flowers, sanitizers and face protective gear, organize themselves systematically every day in order to cater to the public of Queens. By altering their pushcarts, vendors are able to adapt to the environmental conditions. Colorful Sabrett and patio umbrellas provide shade as well as covering from pigeons. Awnings and canopies permit easy attachment of plastic dividers during winter. Heavy concrete blocks and Home Depot buckets filled with cement serve as foundations to define territory.

Temporal coverage and improvised infrastructure are place making tactics that serve as a means to appropriate space and make it their own. Outside resources are brought in to fulfill the needs. Water and gas allow for cooking and cleaning, while generators power lightning at night. Speakers are brought to advertise and perform the liveliness of vending. This act of making place exposes an array of sensory, technical and expressive interactions that create a series of social connections between physical elements, goods, and people. They provide an aesthetic experience that contrast the dominant views and normative beliefs of order in cities like New York.

By conducting interviews to Corona Plaza’s street vendors, residents and nonprofit organizations such as The Street Vendor Project and the New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE), the idea of a push cart garage and commissary emerged. Pushcart commissaries in New York City, run as lucrative businesses that provide storage and restocking of a street vendor’s cart. Instead of this existing model, The Theater of the People project imagines a mutually aided commissary at Corona Plaza. One that is owned, funded and worked by the vendors themselves and the networks of job opportunities they provide. By providing economic and legal support, non-profit organizations could provide a safe haven for the harassed and the marginalized.

The Theater of the People project recognizes street vendors in Corona Plaza as merely the visible performance of a network of distributed and transient actors and infrastructure. Simultaneously, an actual theater sits between the plaza and a park, offering a potential political, economic and social connection between the two public arenas. What can a building built for performance teach us when it becomes a scaffold for an entirely different play? How might we imagine a Theater of the People?

Within this practice of everyday life, street vendors produce an inherently social space that’s embodied, processual, rhetorical, and political. What happens when a theater, a space of leisure that gives pleasure from the art of fiction, becomes the backdrop for the script of the street vendor? What would a space for the stateless look like? What role would the politics of aesthetics have? By portraying these relations and connections of everyday life interactions within public spaces, we can think of ways to invent new, inclusive futures.

12:30 – 14:00 EDT /

09:30 – 11:00 PDT

Special Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Equitable Communities

Special Focus Session

Session Description

Panel will explore approaches to building and financing more equitable communities by exploring different real-life examples. Panelists will present the tools and frameworks for community engagement, progressive policies and new approaches to financing equitable community growth and maintaining community ownership e.g. Community Land Trusts (CLTs) and green banks. CLTs will explored from a policy and experiential point of view.

Moderator

R. Denise Everson

CURE Architects / University of the District of Columbia

Presenters

Brett Theodos

Urban Institute

Carlos Claussell

Institute for Sustainable Communities

Line Algoed

Vrije Universiteit Brussel

30-minute

Discussion Break

14:30 – 15:30 EDT /

11:30 – 12:30 PDT

Plenary

1 HSW Credit

Community Health impact from COVID-19

Plenary Description

Panelist will explore how architecture has contributed to Black, Indigenous, & People of Color communities bearing the brunt of COVID-19, and how we do better going forward-can set up the post-pandemic discussion. This panel will explore technical concerns contributing to community health such as safe air quality and movement of aerosols as well as social determinants of health and designing for community connection.

Moderator

Lynne Dearborn, Ph.D.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Presenters

Cierra Higgins

Perkins + Will

Dr. Bill Bahnfleth, Ph.D., P.E.

Pennsylvania State University

Joanna Lombard

University of Miami

16:00 – 17:30 EDT /

13:00 – 14:30 PDT

Research Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Healthy Communities

Session I

Moderator: Michaele Pride, University of New Mexico

Built and Social Environment Impact on Covid-19 Transmission

Ming Hu, University of Maryland

Abstract

Substantial scientific evidence gained in the past decade has shown that various aspects of the built environment can have profound and directly measurable effects on both physical and mental health outcomes at the population level. These effects have been particularly impactful to the already existing burdens of illness experienced among low-income populations and communities of color. However, there are two primary gaps. First, clearly demonstrating the connection between built environment and health disparities has proven to be challenging to the scientific community due to a variety reasons, such as a need for detailed and quality neighborhood data as well as location-based built environment data. Traditional studies have often lumped many important components of the built environment into a blanket socioeconomic status variable. But this approach makes it nearly impossible to tease out discrete housing and community characteristics related to certain diseases. Second, in the past couple decades, the focus on the association between the built environment and public health has been mainly focused on chronic disease rather than infectious disease. Limited studies have focused on built environment factors linked to indoor air quality and subsequently infections disease, such as the physical and structural condition of buildings and homes.

The goal of this research was to investigate the multifaceted interrelationships between the built and social environments and the impact of this relationship on population-level health in the context of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). More specific, this study assessed the relationship between several social determinants of health, including housing quality, living condition, travel pattern, race/ethnicity, household income, and COVID-19 outcomes in Washington, D.C (DC). Using built environment and social environment data extracted from DC energy benchmarking database and the American Community Survey database, more than 130,000 housing units were analyzed against COVID-19 case counts, death counts, mortality rate, age adjusted incidence rate and fatality rate data for DC wards. The results demonstrated that housing quality, living condition, race and occupation were strongly correlated with COVID death count.

1. Hood, E. (2005). Dwelling disparities: how poor housing leads to poor health.

2. The DRA Project (Accelerating Disparity Reducing Advances). Using Healthy Eating and Active Living Initiatives to Reduce Health Disparities. Bethesda, MD: Institute for Alternative Futures; 2007. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://cdn.ymaws.com/chronicdisease.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/healthequity/he_dra_report_08_01_using_he.pdf

3. Saarloos, D., Kim, J. E., & Timmermans, H. (2009). The built environment and health: Introducing individual space-time behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(6), 1724-1743.

4. Perdue, W. C., Stone, L. A., & Gostin, L. O. (2003). The built environment and its relationship to the public’s health: the legal framework. American journal of public health, 93(9), 1390-1394.

5. Spengler, J. D., & Sexton, K. (1983). Indoor air pollution: a public health perspective. Science, 221(4605), 9-17.

Community-Engaged Decision Frameworks for Increased Urban Neighborhoods Resilience in a Warming Climate

Ulrike Passe, Iowa State University

Abstract

Successful urban systems-related climate-action-support tools enable urban stakeholders to communicate and collaborate across and beyond their respective disciplines to identify innovative, transformative solutions to increase urban infrastructure resilience and sustainability. The actions of humans within buildings and the relationship of buildings to their near-building environments (aka microclimate) constitute one understudied urban system with significant impact on urban energy use strongly impacted by a warming urban climate.

This interdisciplinary research team lead by an architect at a large research university collaborates with local community partners to identify evidence-based approaches for the integration of human behavior data, building energy use characteristics, future climate scenarios, and near-building microclimate data. The team of engineers, humanists, data scientists and an architect provides an excellent example how design can lead community engagement. The team has built a prototypical model, which integrates urban trees into urban energy models based on a large-scale inventory and probabilistic occupancy data based on a neighborhood wide energy use survey.

The goal was to build, calibrate and validate an urban energy model for a local neighborhood, to be adopted to other communities. To ensure that these urban energy models are equitable, however, the needs of marginalized populations must be included- especially those most vulnerable to the consequences of a changing climate. The challenge in understanding these needs is that researchers have often struggled to reach and engage underserved populations due to factors such as access, time, language, economic resources, and trust.

The presentation will thus report on two intertwined research strands. First of all, the team’s best practices for gathering data from individuals facing marginalization as well as the application of this residential occupancy data into neighborhood energy models. Human behavior data collection has been conducted at various community events over multiple years to integrate data about neighborhood dynamics and needs: an extensive youth program merged sustainability, technologies (geographic information system (GIS) information and ABM), and action projects.

The second strand addresses trees in urban landscapes and their capacity to modify temperatures in the near-building environment, which is important for reducing summer heat loads on building surfaces. Trees can reduce energy use and improve indoor and outdoor comfort for cooling in summer by casting shade and providing evapotranspirational (ET) cooling. Tree morphology and building data have been integrated in a three-dimensional energy model to estimate cooling due to interception of sunlight.

The team is currently using results with local partners to develop strategies for individual homeowners in resource-vulnerable areas, as well as to inform city-scale policy responses that improve human health and quality of life for example during extreme heat events. The integrative approach will be disseminated broadly as a means to support cities as they make development decisions that integrate the impacts of climate variability and population dynamics in low-resource, vulnerable urban areas.

Koupaei, Diba Malekpour, Manon Geraudin, and Ulrike Passe. 2020. “Lifetime Energy Performance of Residential Buildings: A Sensitivity Analysis of Energy Modeling Parameters.” SimAUD2020, May, 585–91. http://simaud.org/2020/proceedings/93.pdf

Covid Confessionals: A Rapid Response Public Intervention

Rachel Dickey, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Noushin Radnia, University of North Carolina Charlotte

Abstract

Covid Confessionals is a temporary public installation built as a timely response to Covid-19 in the heart of the city (city name omitted for blind peer review). Responding to a call for installations which asked designers to consider Covid-19 measures for social distancing while also appropriating light as a primary medium, the design team developed a collection of “confessional booths” made of iridescent curved walls, defined by a 6-foot radius, which produce a vibrant field of color through play of reflection and light. The confessionals act as room-sized face shields that encourage physical distancing, while also casting colorful raking shadows of color and caustic light effects in response to sunlight and artificial night lit conditions. The ground plane surrounding the urban shields demarcated distancing measures with a corresponding chalk painted grid and a set of vibration activated light pads generously spaced to encourage physically distanced interaction and play.

The Covid Confessionals project acts as a case study for three areas of design research. The first involves the rapid response design and fabrication methods undertaken in the project to quickly provide a space of interaction in the community in time of emergency. This section outlines the methodology of exploring conflict as a creative tool in design of public space and the procedures for a timely response. The second component involves the study of caustics, a lighting effect produced by an envelope of light rays reflected by curved surfaces dependent on materiality and form. This study of light behavior uses ray tracing simulations to aid in design and determine the range of light based effects and patterns. The third research area provides ethnographic studies, observational documentation, and a catalog of social media and local news responses to the project to demonstrate how design can provide a safe space to support the health and well-being of the community in a time of social isolation due to a global pandemic.

Community Health Design: A Collaborative Framework for Improving Public Health Outcomes

Matthew Kleinmann, University of Kansas

Abstract

When the pandemic hit, the shelves of the Dotte Mobile Grocer – a community-owned mobile market grocery store that was designed and built by architecture students – sat empty. The residents who had formed a community council to make decisions for it were unsure how to best proceed: should the mobile market launch into a national public health crisis or wait for a safer moment? To answer the question, a collaborative model of governance was used that gave residents decision-making power through consensus and consent, and was facilitated by participatory methods of design. The community council grew their capacity to feed thousands of food insecure people in their community; raised enough money around their food justice mission to be sustainable throughout the pandemic; and they continue to use methods of design to make decisions together.

The pandemic also brought to light the need for restorative public spaces, where green space and fresh air can improve mental health indicators. In redlined communities, however, the quality of neighborhood parks has been eroded by generations of disinvestment that has left residents on their own to navigate the labyrinths of broken infrastructure and government bureaucracy. Meanwhile, community policing has championed the use of CPTED – or Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design – as a method for improving parks. It is also based upon the Broken Windows Theory, which can lead to over-policing in communities of color. Groundwork NRG – a northeast Kansas City, Kansas environmental justice organization – took that as a challenge to build their own alternative tool that was created by their Green Team, a green infrastructure and youth training program. The Green Team Toolkit has been co-designed by youth living in the neighborhoods that are being designed with, and it has invited neighbors to collaboratively redesign a vacant lot and two parks, leading directly into implementation phases to build trust with participating neighbors.

Both community health design case studies include evidence and context for how designers can reframe their methods of participation and collaboration and put them in service to community experts. Building upon historical methods of participatory design, socially conscious designers can adopt principles of community engagement from public health practitioners and apply innovative research methods throughout the design process. By bringing together the theories, processes, and outcomes of community health design into a cohesive framework, designers can find common ground with communities in need of spatial agency. Though the pandemic did not introduce these conditions – food and park apartheids are the results of a multi-generational epidemic of racism – this moment has highlighted the need for new ways of collaboration, creation, and building. A framework of Community Health Design is possible through the translation of community voices into a shared vision; designing governance structures to build community power; and turning design tools over to communities to define and achieve their own desired community health outcomes.

Anderson, Nadia M. “Public Interest Design as Praxis.” Journal of Architectural Education 68, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 16–27.

Architecture and Participation. Edited by Peter Blundell-Jones et al., London [U.A.], Taylor & Francis, 2009.

Arnstein, Sherry R. “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 4 (1969): 216–24.

Criss, Shannon, and Matt Kleinmann. “Dotte Agency: A Participatory Design Model for Community Health.” The Plan Journal 1, no. 2 (2017): 213–37.

De Carlo, Giancarlo. “An Architecture of Participation.” Perspecta, vol. 17, 1980, p. 74.

Design as Democracy: Techniques for Collective Creativity. edited by David de la Pena et al., Washington, Dc, Island Press, 2017.

Fulton, William K. “Community Learning: Broadening the Base for Collaborative Action.” National Civic Review 101, no. 3 (September 1, 2012): 12–22.

Hester, Randolph T. “Scoring Collective Creativity and Legitimizing Participatory Design.” Landscape Journal 31, no. 1–2 (2012): 135–43.

Luck, Rachael. “Participatory Design in Architectural Practice: Changing Practices in Future Making in Uncertain Times.” Design Studies, 2018.

Sands, Catherine, Carol Stewart, Sarah Bankert, Alexandra Hillman, and Laura Fries. “Building an Airplane While Flying It: One Community’s Experience with Community Food Transformation.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 7, no. 1 (2016): 1–23.

Sanoff, Henry. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. New York, Wiley, 2000.

Till, Jeremy, and Tatjana Schneider. “Invisible Agency.” Architectural Design 82, no. 4 (2012): 38–43.

Smith, Rachel Charlotte, and Ole Sejer Iversen. “Participatory Design for Sustainable Social Change.” Design Studies 59 (2018): 9–36.

New Americans’ Pavilion: A Community Farming Hub for Refugees in Syracuse, NY

David Shanks, Syracuse University

Abstract

What is the agency of architects to intervene in the global exigencies of the present day at a local, community-oriented scale? This paper will introduce a design approach to a small architectural project that intersects broad concerns of social and environmental justice with community-scale priorities of economic sustainability, food security, and clean energy production.

In the past decade, Syracuse, NY has welcomed over 7,000 New American refugees from diverse geographies ranging from Eritrea to Bhutan to Cambodia [1]. While Syracuse has suffered in post-industrial decline since the 1950s, the influx of refugees has helped to stabilize its population while enriching the culture of the city. Many New Americans arrive in Syracuse in unfortunate circumstances, with limited social networks and job opportunities; however, nearly every person has some experience cultivating, preparing, and cooking food. The New Americans’ Pavilion at Salt City Harvest Farm endeavors to utilize the cross-cultural commonality of food to create an important social hub for locals and immigrants alike to exchange knowledge, culture, and food.

Salt City Harvest Farm has provided farmland and job-training programs for refugees in Syracuse for more than five years, but has lacked formal facilities to support its mission [2]. The New Americans’ Pavilion under construction at SCHF will provide facilities for refugee farmers to wash and pack the produce they grow on their allotments. The pavilion will also include off-the-grid, solar-powered cold-storage where produce can be kept fresh before it is consumed or brought to market. The cold-storage will employ a modified window-unit air-conditioner for cost-effective refrigeration with low energy consumption [3]. Furthermore, the pavilion will include flexible community spaces which will be used for teaching, learning, socializing, and dining.

The pavilion is designed as a ‘double-shed’ whose roof slopes are optimized for competing conditions: toward the south, the roof is sloped to maximize incident solar radiation on the solar panels during summer months; toward the north, the roof is sloped to the minimum allowed by the roofing manufacturer’s warranty in order to minimize the volume of the cold storage space beneath. The distinction between the two roof slopes further serves to define the two primary spaces of the pavilion by celebrating the community dining space and protecting the washing/packing space.

This paper will describe the design process that the architects choreographed in collaboration with farm managers and refugee farmers. It will also detail the technical specifics of the design, including the solar electric system and cost-effective walk-in-cooler, as well as the construction process, which relied on local community volunteers as well as nearby university architecture students. The design process and executed project will serve as an argument that, while architects cannot solve global problems alone, they can productively intersect global and local concerns to produce small but impactful interventions in their communities.

[1] Central New York Vitals http://cnyvitals.org/people (Accessed Feb. 27, 2021).

[2] Salt City Harvest Farm http://saltcityharvest.farm (Accessed Feb. 17. 2021).

[3] Wilhoit, John. 2009. “Low-Cost Cold Storage Room for Market Growers.” University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service.

16:00 – 17:30 EDT /

13:00 – 14:30 PDT

Research Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Equitable & Healthy Communities

Session II

Moderator: Thomas Fisher, University of Minnesota

From Postal Networks to Community Resilience

Stefan Gruber, Carnegie Mellon University

Kristen Hughes, Carnegie Mellon University

Abstract

Connecting 150 million households almost every day, the postal network has been America’s central nervous system binding the nation together for over two centuries — ever since Benjamin Franklin was appointed the first postmaster general in 1775. Historian Winifred Gallagher argues that the postal services created America as “the incubator of our uniquely lively, disputatious culture of innovative ideas and uncensored opinions.”[1]

Despite today’s ubiquitous connectivity, the postal mailbox remains the most reliable and trustworthy portal to the world: here there are no hidden privacy policies or personal data breaches. But the postal domain is rapidly changing and under tremendous pressure to reinvent itself. The Internet reduced first-class mail volume significantly, but also increased that of packages by 50 percent between 2010 and 2015, making the postal service a cornerstone of America’s e-commerce marketplace. Unlike other federal services and infrastructures, the post assumes financial self-sufficiency and does not benefit from tax subsidies, yet is constrained by a universal service obligation and congressional oversight. Accordingly, any debate about future postal services takes place in the context of much broader questions about the role of government itself. And while some voices advocate for its privatization, the postal question does not divide along traditional party lines. Particularly in rural (and often red) areas, the social benefits of the postal service seem to outweigh prioritizing cost-efficiency. Thus, beyond its logistic operation, the post assumes an important civic role at the gain of local neighborhood communities. But despite the post’s ubiquitous physical presence and distribution capability, there is no meaningful process to engage with local place-based revitalization, economic development or smart city initiatives. In the context of recent postal reform legislation which stipulates priority for more state and local partners—as well as the ability to consider non-traditional partnerships which augment core-postal services, the time is right to bridge a place and postal divide.

How can the core service of the Postal Service better align with the needs of the places where they are located? How can postal networks and underutilized postal facilities be envisioned as civic community hubs? How and where can facilities and distribution infrastructure adapt and even be repurposed in order to contribute to community wellbeing and resilience?

These questions were at the heart of an interdisciplinary course in which students from architecture, urbanism, design, human-computer-interaction and public policy explored possible synergies between the postal domain and community resilience. Drawing on the authors’ experience of co-teaching the course, this paper reflects on the designers’ agency and capacity to combine systemic thinking, social innovation and place-making in order to reimagine the future of infrastructure beyond the binaries of the smart and the social, top-down planning and citizen-led transformation of cities. Especially against the backdrop of the Covid19 pandemic and the 2021 infrastructure bill, the students’ radical imaginations developed pre-pandemic gain new relevance.

Resilient Assemblages: Expanding Access and Equity through Practices of Piggybacking

Brian Holland, University of Arkansas

Abstract

Amidst growing calls for equity and social justice to once again become an animating force among architecture’s disciplinary agendas, it’s worth recalling modernism’s social ambitions, which—however flawed or misguided—sought to widely distribute the benefits of good design in service of a more equitable society. In contrast to our present circumstances, these ambitions matured alongside a sustained period of public-sector activism that then retreated dramatically in the final decades of the last century. Finn Williams demonstrates the magnitude of this shift with one illuminating statistic. He reveals that at the height of the welfare state in the UK—when the London County Council Architects’ Department was the largest architecture office in the world—nearly half of all architects were employed by the public sector, contributing to the design of social housing and other public works.1 Williams goes on to quote one architect’s reflection on that time: “We were going to build a better and more equal society.”2 Williams then points out that by 2017, following the collapse of the postwar consensus, and after nearly four decades of rampant privatization, the percentage of architects employed by the public sector had fallen below one percent.

This pronounced shift from public to private sector has haunted the design professions for the past four decades, and frustrated architects’ efforts at serving marginalized communities. Will this finally be a moment of reckoning? It’s still much too soon to tell. Given the present scarcity of robust public-sector programs supporting equitable community development and design, how are today’s socially minded architects to practice? For now, architects and designers must devise resourceful strategies for partnering with and elevating undercapitalized and marginalized communities while simultaneously operating within the limitations of a disciplinary economy that is considerably constrained by the predominantly bottom-line interests of the private sector.

It is in this context that “Piggybacking Practices”—an ongoing research project and recent virtual exhibition and symposium organized by this author—presents one possible approach to expanding access and equity in the designed environment through incremental, opportunistic means. Piggybacking practices are multiple-use propositions for anchoring undercapitalized activities alongside other more traditional forms of urban development. Piggybackings exploit gaps or niches in the logics and economies of conventional spatial practice while assembling disparate actors together into new and more equitable and resilient forms of collectivity.

The Piggybacking Practices exhibition highlights a range of formal and informal piggybackings (with and without the involvement of design professionals), and this paper, like the recent symposium, examines roles for architects, designers, and planners in identifying and visualizing latent sites and situations where piggybackings might intervene in the cause of equitable communities. It also reveals how piggybacking practices present opportunities for architects to effectively serve more than one client—to operate with “hidden agendas” in pursuit of alternative values beyond profit by “smuggling” a larger set of design objectives into conventional design contracts. In this way, piggybacking practices present design professionals with opportunities for expanding access and equity in the communities they serve, in part by overcoming the limitations of our own disciplinary economy.

1. Finn Williams, “Designing Upstream: Rebuilding Agency Through New Forms of Public Practice,” in Architectural Design, Vol. 88, Issue 5, New Modes: Redefining Practice, eds. Chris Bryant, Caspar Rodgers, and Tristan Wigfall, (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2018), 106.

2. Ibid, 106. Here, Williams is quoting John Partridge, who worked in the LCC’s Housing Division.

Resistant Resilience: Playing Out Justice In Community Deliberation

Janette Kim, California College of the Arts

Abstract

How can social and racial justice be centered within the deliberative process of public decision-making, especially amidst the twin crises of climate change and extractive economies?

The concept of resilience has risen in design circles with competitions like Rebuild by Design and the Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge (RBD), which venture strategies for absorbing and surviving the shocks of climate change. As a member of an RBD design team, I partnered with planners, economists, biologists, community-based organizations, and government agencies to explore resilience in Deep East Oakland and the San Leandro Bay. Our Oakland partners have had far too much experience with resilience—they are well-versed in bouncing back from the exodus of manufacturing jobs, redlining, public housing demolition, and rapid gentrification. It is no surprise, then, that RBD was met with deep skepticism as a smokescreen for gentrification. Discussions among such a heterogeneous team highlighted not only the need to build a regenerative economy and adaptive landscapes, but also the intransigence of real estate speculation, neighborhood self-interest, and even the analytic language of bureaucracy.

To prompt this expanded team to embrace these debates, I designed a board game called “In It Together” alongside our collaborative process, in real time. This paper reflects on this board game as a empowered decision-making tool for building empathy among stakeholders and modelling risk within urban spaces.

In It Together stages role-play among community stakeholders to reveal how sea level rise will amplify alliances and conflicts among them. The game made it safe, and even fun, for us to expose conflicts typically smoothed over by a goal-oriented design process. It builds empathy by inviting partners to perform each other’s perspectives. It also models the impact of urban adaptation strategies—defined with our partners to range from a community land trust to a raccoon den—in the urban space of the board. The game scores points for ecology and equity as well as economy, and issues currency in votes as well as dollars. Thus, soft judgements have equal weight as hard evidence—from ethics, strategy, and lived experience to the economic or hydrological performance. Values of justice and resilience contend with development and self-protection.

I propose to unpack play scenarios and lessons from over 30 events with activists, agencies and others, both during RBD and since. I will then recontextualize these findings among other decision-making tools, in part to demonstrate how our agonistic stance helped us evade the pitfalls of deterministic choice raised by Jennifer Light in her critique of board games used in the 1966-7 Model Cities and the condescension between expert and “childlike” representational styles raised by Shannon Mattern’s excoriation of Sidewalk Toronto’s participatory workshops. What has proven most elusive, however, is In It Together’s ability to facilitate consensus among different styles of communication—skills I hope to learn from the Brazilian Workers’ Party’s invention of “participatory budgeting” in the 80s. It is with these critical skills that deliberative processes can forge a more nuanced vision of resilience—one that resists precarity while adapting to uncertainty.

Author (2021). “Modelling a Critical Resilience: Board Games and the Agonism of Engagement.” Games and Play in the Creative, Smart and Ecological City, Eds. Dale Leorke and Marcus Owens. UK: Taylor & Francis.

Author (2020). “Daylighting Conflict: Board Games as Decision-Making Tools,” in Scenario Journal, Issue 07, “Power” Ed. Nicholas Pevzner & Stephanie Carlisle. Winter.

Author (2018). Year in Review 2018: Whose Resilient Future? Metropolis Magazine.

Arnstein, S. (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, Vol.35 Issue 4.

Beck, U., & Ritter, M. (2013). Risk society: towards a new modernity. London: Sage Publications.

Chandler, D. (2014). Resilience: the governance of complexity. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Halpern, O. (2017) Hopeful Resilience. e-flux architecture, Accumulation.

Holling, C. S. (1973) Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecological Systems 4.

Kang, S. (2018). “I have a right not to be resilient” The Migrationist.

Klein, N. (2007). The Shock Doctrine. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. Crown.

Latour, B., & Porter, C. (2009). Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Light, J. (2008). Taking Games Seriously. Technology and Culture, Vol. 49, No. 2.

Mattern, S. (2020). Post-It Note City. Places Journal.

Mouffe, C. (2000). Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism. Reihe Politikwissenschaft, Political Science Series No. 72.

Self, R. O. (2005). American Babylon: race and the struggle for postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Place-Making through Storytelling

Jennifer Smith, Auburn University

Abstract

Baptist Hill Cemetery, located in Auburn, Alabama, is a historic African-American cemetery dating back to Emancipation in 1863. While a prominent landmark sited at the terminus of a historic road east of the university’s campus and resting atop Baptist Hill, its rich past is scarcely known. The cemetery is one of a few remaining African-American landmarks in the city, and there is a movement to protect these assets and communicate Auburn’s story through the site and neighboring areas.

This paper discusses the on-going research and design work of place-making through storytelling and creating quality and accessible public spaces using participatory design. It focuses on the Baptist Hill corridor in Auburn as there are numerous community assets including: historic Baptist Hill Cemetery, historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, the public library, the city recreation center and two primary schools, one of which was the African-American high school during segregation practices. While each site is within a quarter-mile radius, there is opportunity for enhanced operational and physical connections by means of education, storytelling, pedestrian corridors and appropriate public spaces.

This work is in partnership with the city of Auburn, individual program directors, assemble design group and a university course. Work includes participatory design, site analysis, asset mapping and vision casting with the goals of an expanded understanding of community needs, awareness of site and program challenges and opportunities, and appropriate storytelling of Auburn’s African-American history.

Public Space + Scrutiny: Examining Urban Monuments through Social Psychology

Emilie Taylor Welty, Tulane University

Lisa Molix, Tulane University

Tiffany Lin, Tulane University

Abstract

With fewer than 1 in 5 new architects identifying as a racial or ethnic minority, the field of architecture has some catching up to do in order to reflect the public for whom urban spaces are designed.1 This paper will discuss a study of existing public spaces, monuments, and memorials through the lens of social psychology, in order to establish a broader frame of reference for future design. We will employ an interdisciplinary approach to investigate community members’ reactions (e.g., stress, positive/negative associations, value judgments, perceptions of bias, inclusion, empowerment) to experiencing public spaces and monuments that memorialize contentious historical figures and events. Using a community-based participatory action approach (e.g., focus groups, survey study), we will identify elements of design (e.g., scale, materiality, abstraction, figuration, symbolism, color) that contribute to the general public’s perceptions of public spaces and monuments. Data gleaned from the first phase research study will generate the framework for the second phase of applied research, conducted through an advanced architecture design/build studio. Using a data-driven, community-informed strategy, the design/build studio will collaborate with the research team and community partners to explore proposals that work to bridge the gap between the architects and the general public when creating urban spaces marked by racial injustice.

There are many examples of governing bodies that have made decisions about removing or renaming contentious public spaces, monuments, or symbols. While the processes have varied, a review of documented examples suggests that some decisions are made based on a perceived incompatibility between the initial intent of an institution and current institutional values. Although conversations surrounding public memory and social justice are at the forefront of architectural pedagogy and practice, very little of the empirical work on re-contextualizing these public spaces has included the voice of designers or members of the communities in which these spaces/monuments exist. This project will examine the differences in perceptions of public monuments and aims to equip architects with the skill set to engage with communities when searching for equity, inclusivity and truth in collective forms of commemoration. As we work to teach values of design that build a more sustainable and equitable future, projects such as this can help both students and professionals in design fields gain a deeper understanding of and commitment to the relationship between design and social justice.

1. National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) 2020 Demographics Report

Block, Melissa. “Push To Remove Confederate Monuments Opens Debate On Other Honored Historical Figures.” National Public Radio, 2 July 2020.

Butz, David A. “National Symbols as Agents of Psychological and Social Change.” Political Psychology, vol. 30, no. 5, 2009, pp. 779–804.

Croegaert, Anna. “Architectures of Pain: Racism and Monuments Removal Activism in the “New” New Orleans,” City & Society, 2020.

Doyle, D. M. & Molix, L. (2014). Perceived Discrimination as a Stressor for Close Relationships: Identifying Psychological and Physiological Pathways. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 1134-1144.

Draper, Robert. “Toppling statues is a first step toward ending Confederate Myths,” The National Geographic: History & Culture, July 2, 2020.

Fausset, Richard. “A Voice of Hate in America’s Heartland.” New York Times, 25 Nov. 2017.

Kendi, I. X. How to be an Antiracist. Bodley Head, 2019.

Molix, L., & Nichols, C. P. Satisfaction of Basic Psychological Needs as A Mediator of the Relationship Between Community Esteem And Well-Being. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2013.

“Reconsideration of Memorials and Monuments.” American Association for State and Local History History News 71, no. 4, Autumn 2016.

National Council of Architecture Registration Board. Annual Demographics Review: https://www.ncarb.org/nbtn2020/demographics

Stonorov, Tolya. The Design-Build Studio: Crafting Meaningful Work in Architecture Education. Routledge, 2017.

Tatum, B.C. Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria. Basic Books: New York. 1997.

Wright, J. D., & Cheung, I. Is Support for Confederate Symbols Motivated by Southern Pride or Racism? Further Distinctions Between “Traditionalists” and “Supremacists,” 2019.

16:00 – 17:30 EDT /

13:00 – 14:30 PDT

Special Session

1.5 HSW Credit

Healthy Communities

Special Focus Session

Session Description

This session will highlight partnerships between practice and academia in consortia transforming how we think about healthy buildings and communities. Community-based projects and engagement will be highlighted through those partnerships between practice and academia in context of community improvement through better health outcomes. Leaders and health experts from multiple firms will present projects and illustrate how research has influenced outcomes.

Moderator’s

Heather Burpee

University of Washington

Panelists

Anne Schopf, FAIA

Mahlum Architects

Vikram Sami, AIA, BEMP, LEED AP

Olson Kundig

Myer Harrell, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

Weber Thompson

Christopher Meek

University of Washington

Kristen Dotson

Miller Hull

Pia Weston, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

SHKS Architects

30-minute

Discussion Break

Eric W. Ellis

Senior Director of Operations and Programs

202-785-2324

eellis@acsa-arch.org

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL