How to Manage Your Online Scholarly Identity

Barbara Opar and Lucy Campbell, column editors

Column by Anne E. Rauh, Science & Engineering Librarian, Syracuse University Libraries

What is the first thing you do when you receive an announcement about a speaker or a new colleague joining your institution? Do you want to find out more? I know I do. What happens when you search for yourself online? Do you discover old webpages listing outdated works and previous employers, or a true reflection of you and your work? Today a number of mostly free tools are available to collect and present accurate up-to-date information about scholarly identity.

When librarians and faculty ask me what they can do to curate their online profiles, the first tool I recommend is LinkedIn. With more than 400 million members in 200 countries worldwide, Linkedin allows you to create connections that represent your real-world professional relationships while expanding your network. Although largely a business-oriented social networking tool, Linkedin can serve academics too. Whether interacting with architecture firms, seeking to place students in internships, following alumni as they progress through their careers, or looking to find out more about publishers and material vendors, LinkedIn can help. An established network can help you find employment opportunities, recruit candidates, identify collaborators, highlight achievements, and notify colleagues and peers of job changes and other achievements. However, while LinkedIn does highlight academic work, scholarly identity is not the main focus. For that the internet offers some more specialized tools.

My top recommendation for a tool to profile scholarly work is Google Scholar Citations. This feature of Google Scholar requires very little effort and after initial set up, automatically populates a scholar’s profile with their citations. After logging in using your Google account information and verifying the publications Google Scholar has located are in fact yours, you can add affiliation information and keywords about research interests to enrich your profile. If publications are not automatically populated they can be added manually. Profiles update automatically or can be moderated as new works are published. In addition to a list of publications, Google Scholar Citations shows metrics such as h-index and total number of citations. These profile pages are easily found when searching in Google Scholar.

Scholarly communication practices are changing with websites integrating scholarly publishing and social networking. This does promote interaction and sharing of scholarly materials. Referrals from social media aid in discovery. Two widely used academic social networking tools are Academia.edu and ResearchGate. Academia.edu boasts more than 39 million members and ResearchGate claims over 10 million. Academia.edu users come from all disciplines while the majority of ResearchGate users are from the health and life sciences. Despite its name, Academia.edu is not an institution of higher learning or a consortium of academic institutions but rather a domain name registered before restrictions were placed on the use of ‘edu’. ResearchGate is the largest academic social networking site and does require a referral or institutional affiliation which can be verified. Both tools encourage authors to upload papers and share within their network. Users can also request that authors upload and share papers not currently available. When papers are uploaded, they are attributed and a profile is created showcasing all the authors’ works.

Both tools have received a fair amount of criticism from user communities. Users of ResearchGate complain about the number of system-generated notification emails. Whenever a paper is uploaded, an automatic email is sent to co-authors inviting them to use the tool. ResearchGate has also been criticized for how it calculates journal impact as well as its auto-generation of author profiles Both tools are frequently confused for open access repositories and do not fulfill institutional or funding agency requirements to share work. Both sites also encourage authors to disregard copyright agreements, something that publishers are not ignoring. If you are interested in what you as an author can do to retain copyright, see AASL’s October 2015 column post by Amy Dygert.

Your institution may also have solutions to help manage online scholarly identity. At Syracuse University, we have SelectedWorks and Experts@Syracuse. SelectedWorks is a feature of SURFACE, our institutional repository, hosted by Digital Commons. This feature allows authors to profile their work in an organizational format that works for them. It links to content hosted in the institutional repository and allows for uploading and linking of additional content. Experts@Syracuse is driven by Elsevier’s Pure. It connects to Scopus author profiles, and local information such as appointments and grant information is added by the institution. Ask your library or research office if there are similar offerings at your institution.

If you are curious what any of these look like in action, I maintain the following sites:

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL

Understanding the idea of the “total work of art” can be an important lesson for students and, recently, more attention has been drawn to it. Gesamtkunstwerk has once again become a subject of numerous discussions, proving that this idea is still relevant. The exhibition, “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” in Kunsthaus Zurich (1983) and in Vienna (1984), a recreation and performance of Skriabin’s “Prometheus” at Yale University (2010), and the latest collection of essays, “The Death and Life of the Total Work of Art,” presented at the Bauhaus Colloquium in 2013, highlight the historic meaning of the term, and apply it to more recent events and works. Technological advancements provide the tools that allow for the creation of immersive artistic experiences, which remove “the borderline between object and observer, stage and audience, art work and spectator,”

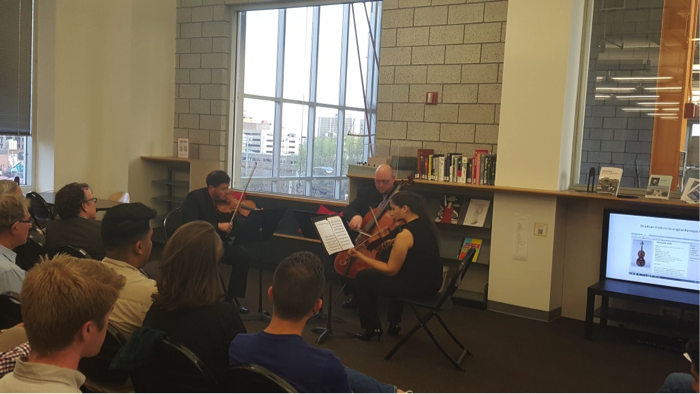

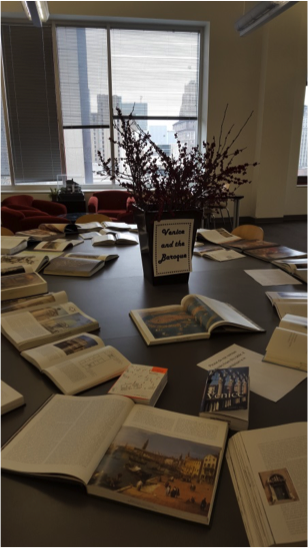

Understanding the idea of the “total work of art” can be an important lesson for students and, recently, more attention has been drawn to it. Gesamtkunstwerk has once again become a subject of numerous discussions, proving that this idea is still relevant. The exhibition, “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” in Kunsthaus Zurich (1983) and in Vienna (1984), a recreation and performance of Skriabin’s “Prometheus” at Yale University (2010), and the latest collection of essays, “The Death and Life of the Total Work of Art,” presented at the Bauhaus Colloquium in 2013, highlight the historic meaning of the term, and apply it to more recent events and works. Technological advancements provide the tools that allow for the creation of immersive artistic experiences, which remove “the borderline between object and observer, stage and audience, art work and spectator,”  university community, the concerts are mostly focused on the needs of the College of Architecture and Design population. The concert series directly supports several courses, including “Music for Designers,” which is focused on the theory and history of music, its relation to culture, and its use in cinema, digital and interactive media. Each concert is accompanied by a short lecture and PowerPoint presentation related to the theme of a concert, providing context as well as background information. Students design posters advertising the series. A book exhibition further enhances each event. The collaboration with musicians–a group of talented and dedicated educators–helps to develop programs that are both popular and educational. These events take place in an intimate “chamber-like” environment of the college Library which is located in the physical center of the building. Folding chairs that can be easily assembled form an auditorium. The Library remains open and fully functional during these events, which usually take place at night. Light refreshments help to create a pleasant and relaxing atmosphere. Free of charge, funded and supported by the college administration and alumni, these concerts have become popular and well attended. They help to alleviate stress, expand students’ horizons, improve their exposure to music, link performed musical compositions to the subjects of study in classes and studio, provide a historical context, and establish the Library as a place which can provide cultural and educational opportunities, often not possible within a curricular setting.

university community, the concerts are mostly focused on the needs of the College of Architecture and Design population. The concert series directly supports several courses, including “Music for Designers,” which is focused on the theory and history of music, its relation to culture, and its use in cinema, digital and interactive media. Each concert is accompanied by a short lecture and PowerPoint presentation related to the theme of a concert, providing context as well as background information. Students design posters advertising the series. A book exhibition further enhances each event. The collaboration with musicians–a group of talented and dedicated educators–helps to develop programs that are both popular and educational. These events take place in an intimate “chamber-like” environment of the college Library which is located in the physical center of the building. Folding chairs that can be easily assembled form an auditorium. The Library remains open and fully functional during these events, which usually take place at night. Light refreshments help to create a pleasant and relaxing atmosphere. Free of charge, funded and supported by the college administration and alumni, these concerts have become popular and well attended. They help to alleviate stress, expand students’ horizons, improve their exposure to music, link performed musical compositions to the subjects of study in classes and studio, provide a historical context, and establish the Library as a place which can provide cultural and educational opportunities, often not possible within a curricular setting.