Exhibit Charrette

Communicating Humanitarian Shelter

Online Discussion

Communicating Humanitarian Shelter

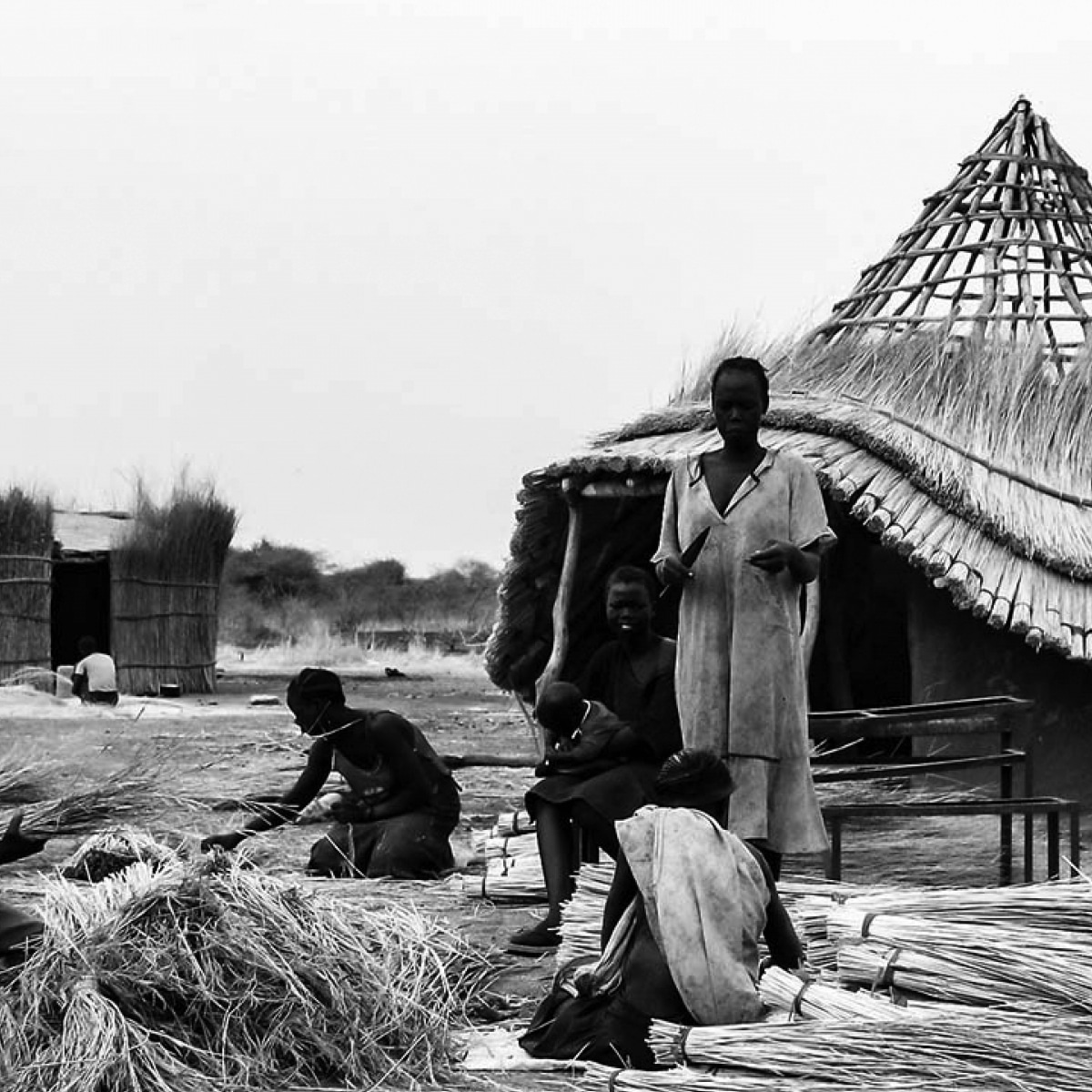

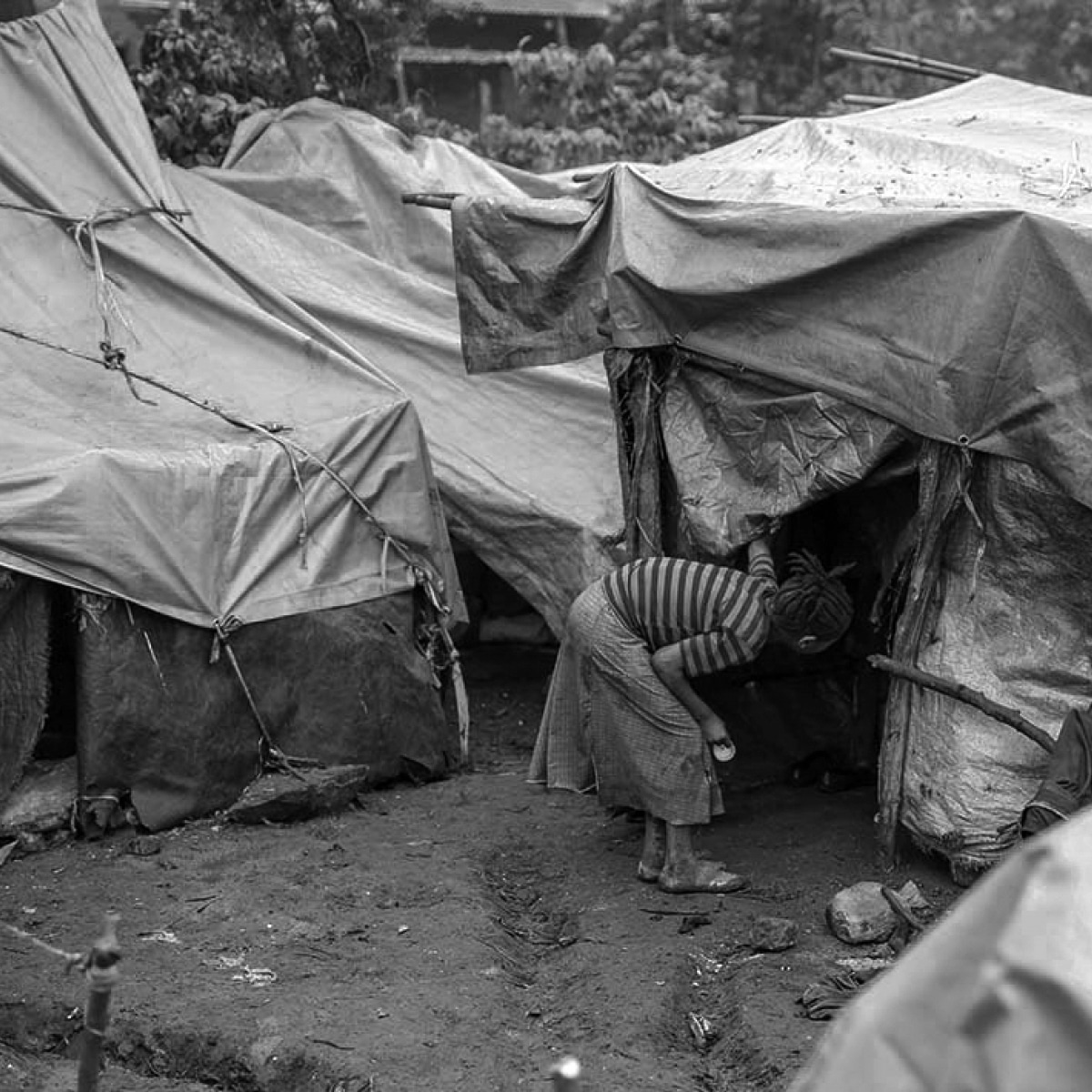

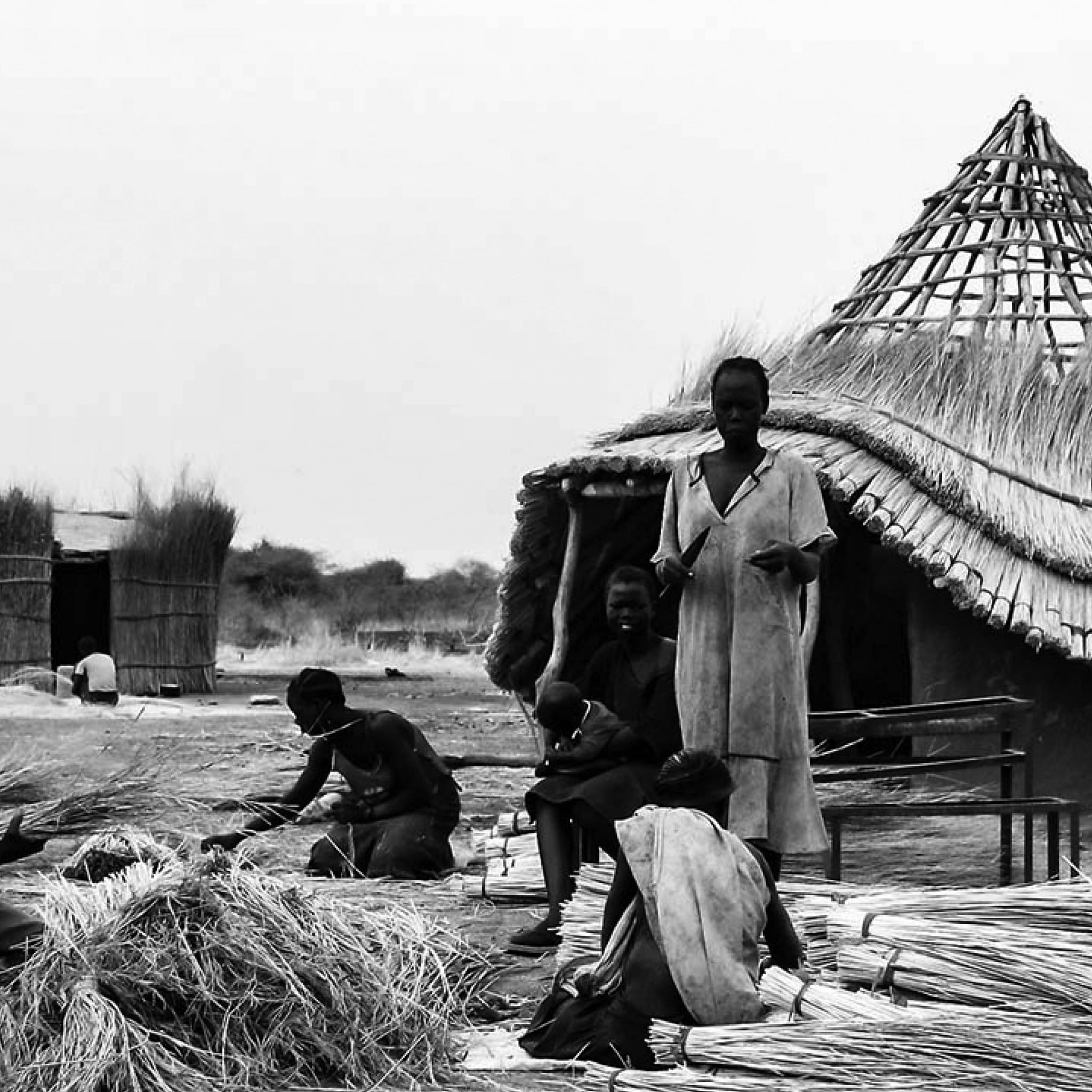

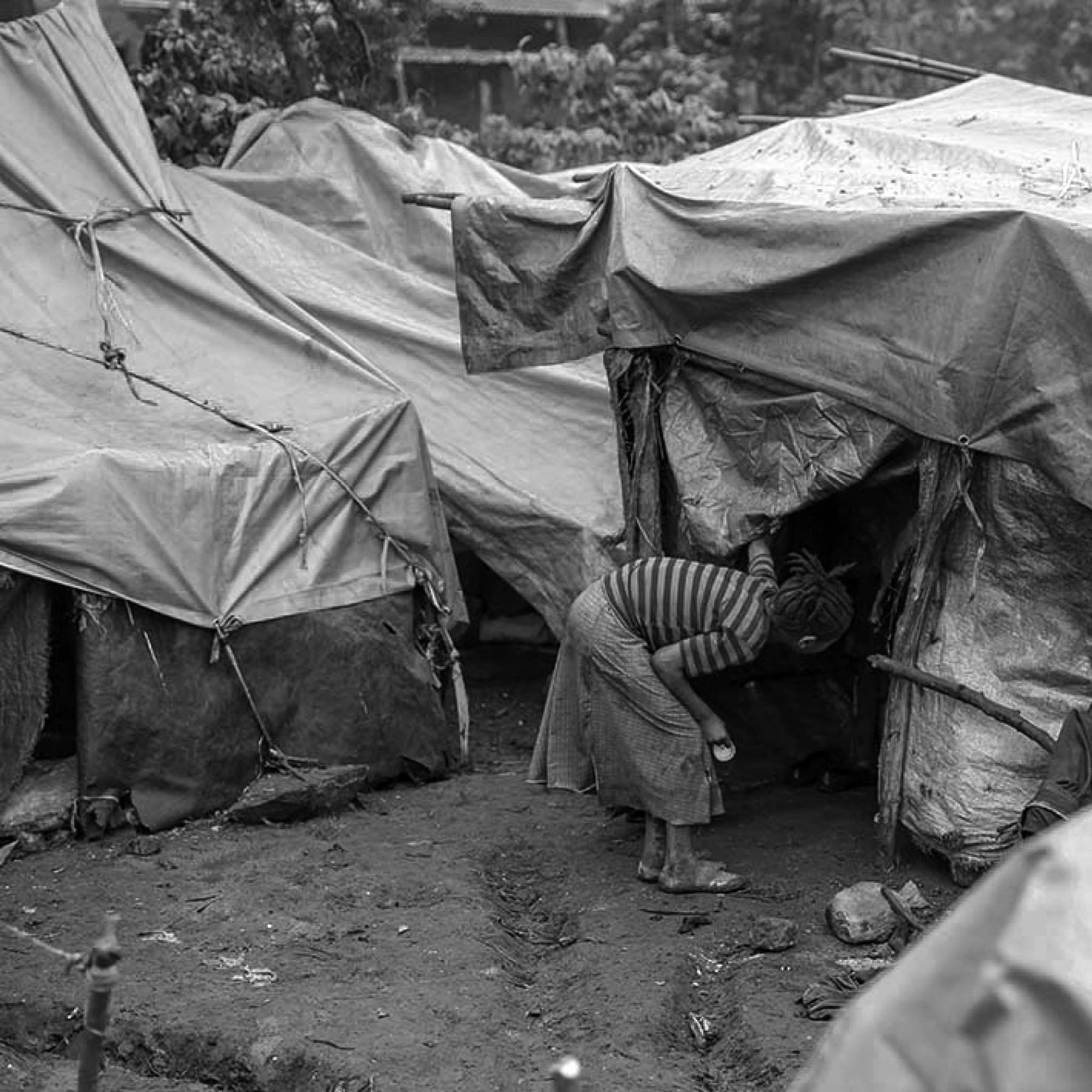

What is Humanitarian Shelter? When people’s houses are destroyed by disasters or conflict they need shelter. Shelter is not just the walls and the roof that provide protection from the weather but also it needs to enable people to live their lives in safety. Humanitarian organizations work to assist people to find and improve their own adequate shelter.

Shelter and settlements assistance is essential to safeguard the health, security, privacy and dignity of individuals affected by crises. Beyond just lifesaving, shelter and settlements assistance is fundamental in rebuilding the psychological, social, livelihood and physical components of life – in short, all the aspects necessary for people to move from survival to recovery.

How can architects and designers provide assistance? Learn more in this online discussion.

This online discussion is in conjunction to the 2025 Exhibit Charrette.

Online Discussion Part 1

October 28, 2024

Q & A

Q: You talked about looking at crises that have happened, for example the flooding that’s been going on throughout the United States due to the hurricanes, but what about crises that we know that could happen. Should we look to design for those groups beforehand and after the crisis occurs?

A: This is a question about disaster risk reduction and preparedness, which is one component of the whole cycle of disaster management. When talking about humanitarian shelter and settlements, the question is, “What happens after the disaster hits”? How do we provide humanitarian shelters to ensure that things are designed so that it doesn’t happen again? In the US, we do have systems in place. We have FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency. We have the government, which can appropriate funding for reconstruction and rebuilding. And there is normally funding coming in and coordination happening. This happens quickly. The challenge is international, those funds may not always be available in advance or limited when they are available. The support that is being provided for humanitarian shelters and settlements internationally is very limited, a lot of times, not much more than around $300k per family. So people’s capacities to respond may be greater than here in the US.

Q: When you mentioned land rights, tenure and how that links to stability. Oftentimes these land rights are based on the policies set by the countries of refuge, for example, Uganda is a big host of a lot of countries like Rwanda and all the East African countries that have had a lot of refugees come out of there in the past 27 plus years. During the process, do we engage with these countries of refuge and their policies and how do we take that on, or is that too much of an overstep?

A: There’s quite a bit to unpack in that. The first part is that there’s a big difference between a refugee, who’s someone who, through a well-founded fear of persecution, has crossed an international border, and an IDP – an internally displaced person within a country. When someone crosses an international border, then they become subject to more international law. There’s an international agency, the United Nations High Commissioner for the Refugees, that is mandated to assist refugees, but ultimately, countries of refuge are the ones who are primarily responsible for the safety of those people. With IDPs, it is the responsibility of the state to look after their population. This leads to very different environments and different legal frameworks. You’re right to highlight land if there’s no land, then you can’t build. If you’re doing humanitarian response, you’re giving someone a tarpaulin or even a piece of plastic; you’re giving them some form of claim over a place because occupancy is a degree of ownership. So with any form of shelter, any form of housing, any form of emergency attempt to give someone somewhere to live, you’re by necessity engaging with land rights. You also need to ensure security of tenure, but it also depends on the legal framework and the context where you’re in. So first, you need to understand whether you’re working in a refugee or an IDP context.

Q: How can architects build so that they are keeping in mind the different hazards that could impact the communities that they’re working with, but also when the impact has already happened, there is a whole path for recovery that is very long and being aware that it’s not necessarily something that happens quickly.

A: So what I would say in the case of architects, they should try to look into what are the strengths of the population and what can they do. A lot of times it is more efficient to try to work with people with what they know and try to recover than just providing things off like a turnkey kind of solution that may not always be feasible. And understanding the risk and understanding that there’s not one single disaster. Sometimes, there’s an overlap of disasters that can happen, and not only plan for one type of hazard, but plan for multi-hazards and understand those. I think being in a country that may not be able to mobilize the funding to support the population is part of the challenge that we’re trying to tackle here, and what we want people to understand is that shelter is the core.

Q: I would like to know about vernacular construction, self-construction, and prefabricated construction, the paradigm of building quality and minimizing risk, time, durability, and price cost.

A: This is one of the key pieces, and there’s always a tension between how much support you can provide and at what level and how many people you can support. While it would be great to be able to provide everybody with a prefabricated solution, funds scarcity means that with comparatively expensive solutions, we will end up supporting less than 10%. Once you go into finished solutions, the funding gets even smaller for the number of families that can be supported. That is why what we’ve been trying to do in the sector is to try to support as many people as possible. And that means sometimes having less funding per family, allows for families to be able to self-recover. There are tensions that often budgets are limited. On the other hand, families are often more able to maintain and expand those constructions that they’re familiar. The core that might be provided in a prefab solution might be safe, but whatever families can add to it may not be safe, and we might be putting people at risk if they’re not able to provide something that fully addresses the structural standards of it.

Q: My question is about the format of the charrette exhibit itself. Is this going to be digital? Should we focus more on developing countries?

A: There is no limitation on format. Whatever format you feel will be your strength in communicating humanitarian shelter is fine. Basically, in terms of the context, the purpose is to explain and communicate what international humanitarian shelter and assistance is so that we can look at the global gaps on where we are with humanitarian assistance globally and what the role of the architect is in thinking through, and what the principles are. So, trying to communicate what shelter is. The first step is to select the students through their understanding of humanitarian shelters and settlements. The basis to design what needs to be designed will be given at the charrette. So, you guys are not necessarily submitting a design right now; it is more about what your interests are in humanitarian shelter. You may have an idea of how to abstractly communicate humanitarian shelter and settlements; you can add it to your interest statement, but you will be provided with the problem statement at the charrette. That’s the purpose of the charrette itself. The webinars are for you to get more acquainted with what humanitarian shelter and settlement are, so you can do a bit of homework before you submit your application. The design sample is to see your ability to design, and the statement is your motivation to be part of the charrette. And then, at the charrette, there will be design parameters.

Q: Why are we designing an exhibition?

A: To develop an exhibition you need to be able to articulate ideas incredibly clearly and to do that you need to understand the ideas and understand the concepts. So the purpose of this is really to understand the concept behind what humanitarian shelter is and open that to an audience. Once people understand these concepts, then the exhibition is about communicating those ideas. So really the purpose of the charrette is to improve understanding and broaden the audience. We’re looking for design and communication skills and the ability to understand the underlying problem, the problem set, which is understanding the concepts and ideas behind what humanitarian shelter is.

Q: For the charrette, what should be the focus of the interest statement? Also, what type of design work samples are you looking for? Could you clarify how to frame both elements (interest statement & sample design work), so that it’s cohesive, and it communicates a strong proposal.

A: The students need to showcase how well they understand humanitarian shelter and settlements. Being an architect myself, I would investigate ephemeral architecture, anything that has been done in that area from that design perspective. If the student has had previous engagement with this type of problem or problem-solving, it would be beneficial to highlight it. Ultimately, for the charrette, the students will be responsible for designing the envelope of the exhibition but also understanding the content so that both the envelope and context speak together effectively and communicate.

Online Discussion Part 2

November 26, 2024

Q & A

Q: Does IOM monitor and evaluate procedures from the perspectives of the people that inhabit the shelter? How do you balance external international organizations’ ways of measuring adequate shelter versus residents’ own definition of what is adequate?

A: The fundamental point is people themselves are not usually passive in finding their shelters. Our role as international organizations is how do we enable that, but also how do we enable it with incredibly limited resources. I think we’re probably often talking about, on average a $200-$300 dollars budget per household for a crisis response. The majority of crisis responses are non-food items, basic distribution of items or basic distribution of provisions, and a minimum amount of cash or vouchers. We’re often struck with the dilemma of do we do a high level of assistance and good quality impactful assistance for a small number of people, or we do more minimal forms of assistance for a larger number of people? There are many ways of getting feedback, including discussing with people in the community, individual groups, doing surveys, and then designing programs that are flexible enough to provide different levels of assistance for people is the difference between a good program and a bad program. In terms of self-identification, a lot of research has been done, but we need to do more. Unfortunately, we have differing standards around the world of what we’re able to provide or what the expectations are, partly because of people’s perceptions that are based on the experiences they have, but also because we know that budgets are not consistent between countries and responses. The dilemma is, do you provide a high level of assistance for a few people or less assistance for more people?

Q: What makes a shelter not just a roof but a home thinking of the International Federation of Red Cross video called Shelter Effect?

A: When you think of a house and what makes a shelter is having access to all those minimum services, either because of proximity or because they are in the house that a family can carry on. We used to say that a house without, for example, access to sanitation or a bathroom is not a house, it’s a warehouse. That video of the shelter effect (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lf2z38u2djA) is also very focused on disaster risk reduction and how the house provides safety from the elements. As a result of multiple issues, including climate change, a lot of the different hazards are impacting the house, which are recurring. In this case, it was flooding, and by designing a shelter that can be above the flooding level, people can then reinvest the money that they were using to repair it every year to invest in their livelihoods. It’s this concept that shelter is the platform for every other area of your life to thrive. If you don’t have that basic shelter or a home, it’s very difficult to thrive.

Q: Do you ever take into account the actual resources available after the disaster occurs? For example, locations have warehouses that are probably housed with building materials, housed with ready to go materials for the rebuilding effort. Having limited resources when a disaster occurs, there is no guarantee these places are not going to be hit by the disaster. So, going in with the mindset of rebuilding, the resources available on the ground versus bringing in resources. I’m just trying to get a feel of the assessment.

A: The first line of defense is the people themselves, and they are going to be looking into their local materials. There are a lot of organizations that focus on trying to get what is local. That’s why cash distributions have started to be one of the preferred ways of support. Those use the materials available in-country, and what we normally do with those kinds of programs is try to support the value chain for the materials that may not be available that easily. For example, in the Philippines, we know that when a typhoon happens, it’s very easy for the corrugated iron sheet to sell out in the market. So, that is why, in some cases, you might be bringing what may not be that easily available, and you do a market assessment before making a decision on whether or not you’re providing cash or you are providing materials. When the level of devastation is so huge that markets are not working, you begin shipping things into the country. This was very clear, for example, in Haiti, being an island after the earthquake in 2010, and with most of the infrastructure damaged by the earthquake, it was hard for even some of the local staff to operate. The local markets were not necessarily working, and then shipping things in was even more complicated. Each crisis is unique, and you do need to investigate those assessments to see what’s available and how you can complement it in your response.

Q: With material distribution, is local material ever prioritized when sourcing?

A: There’s usually a combination, so you do prioritize, and you do try to make sure that people can rebuild with local materials. To highlight the Domes photo I showed, which was a 1970s experiment, every time there’s a big crisis, we see loads of inventions, often with imported materials, which don’t work because they don’t consider not only how people build, particularly in rural environments or in low-income environments, build incrementally over time. They also build with materials that are more familiar to them at a very low cost or low cost over time. So often, bringing in imported materials, and imported structures, comes with a very high cost. If you’re spending $2,000 for a shelter, plus the air freight, that’s fewer people you can assist. We often try to tie response to the use of local materials to be able to deliver at scale and with materials that people know how to build with and maintain.

Q: Are there any assessments made about zones, like safe zones for relocation safety for these individuals ahead of time. When a disaster does hit, is there a contingency that there are areas people could safely be relocated to in a more expeditious manner because you already studied that location?

A: Emergency evacuation for temporary disasters happens a lot, and if you go to places where there have been tsunamis, you’ll hopefully see planned evacuation routes. In Bangladesh, they’ll have cyclone shelters, for example, where people can go, which are schools during the normal season and are short-term evacuation planning. Relocation happens often, but it is also important to consider why people would want to relocate away from land that they may have lived on for generations and the actual advantages and disadvantages of sites, particularly as they affect people in informal settlements. Particularly, poorer people often live in very vulnerable locations quite often, and they live there for reasons. Often, it’s informal land that has access to jobs, livelihoods, agriculture, fishing, etc. For example, there are lots of urban areas that are located where rivers meet on earth seismic zones and alluvial plains. There are various historical reasons people have settled there, so when you start relocations, it can come with the risk of them not being to places where people want to live. Relocations can also move people away from valuable land that developers are trying to move them far away from. There are often plans for new towns or new settlements on very low-value land or land with political background objectives as to why people in power want people moved, which may or may not be to the advantage of already vulnerable people. Whenever you’re getting involved in any kind of post-crisis relocation or even planned relocation, you have to think through whether it’s going to be to the advantage of the people living there or the most vulnerable people. The actual risk calculation is that people who are displaced worry about work, access to jobs, livelihoods, schools, and other services. Those types of studies are the responsibility of the sovereign government of each country, and at times, it’s at the municipal level. When a humanitarian organization comes in to support, this tends to be when things at the local level are not necessarily able to respond. Understanding local policy and government policies and how they have been done in the past is part of what we try to do as humanitarian organizations in humanitarian shelter.

Q: What kind of design sample is expected?

A: Ideally, it would be something from your portfolio. At this point, we’re not looking for you to design something specifically for the interest submission. We’re looking more at your level of interest, your background, and what you might already have in your knowledge base and in your design skills that would be beneficial to be able to be an exhibition designer. We’re looking for problem-solving skills that would show some of those techniques that you might have learned through some of your more formative years in architecture education that would help to relay that you have some of that knowledge. In tandem with the 250-word statement, the imagery is going to be an assistance because this is a design problem. Your interest submission should express your knowledge, research, and design.

Irantzu Serra Lasa

My mission is to contribute to a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable world through impactful organizations in partnership with local communities. I provide expert advice and strategic leadership on Disaster Risk Management, Disaster Recovery, Urban Development, Housing, Land, and Property rights (HLP) in crisis contexts, strategic planning, and client/social safeguarding. I collaborate with international organizations, academic institutions, and government agencies to design and implement innovative solutions to increase community resilience to disasters and crisis through safeguarding and strengthening their built environment, and a people centered approach.

As an architect and urban planner, with 20+ years of experience in the nonprofit, academia, and private sectors, I have led multidisciplinary teams across Asia Pacific, Europe, and the Americas. I am passionate about building and fostering high-performing teams, ensuring program quality and accountability, and creating value for organizations and communities. I was selected as part of Cohort XIX of the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at Harvard University which has allowed me to be part of an extensive network of leaders in disaster and crisis management work. I am culturally sensitive and fluent in Spanish, English, and French.

Joseph Ashmore

Humanitarian professional with more than 22 years experience in leading teams in global operations, policy development in UN, NGO and EU Civil Protection organisations. Extensive expertise in systems change management, coordination, strategic planning, consensus building and facilitation. Core skills in building capacity of staff, technical writing, and team and project management have been developed through hands-on programming. Specific technical expertise in Shelter & Settlements, CBI, WASH, Supply chain, operational protection and GBV mainstreaming. Holds a masters in International Negotiation and Policy at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL