March 30-April 1, 2023 | St. Louis, MO

111th Annual Meeting

IN COMMONS

Schedule

June 8, 2022

Abstract Deadline

August 2022

Author Notification

October 12, 2022

Submission Deadline

December 2022

Presenter Notification

March 30 - April 1, 2023

ACSA111 Annual

SCHEDULE + ABSTRACTS: SATURDAY

Saturday, April 1, 2023

Below is the schedule for Saturday, April 1, 2023, which includes session descriptions and research abstracts. The conference schedule is subject to change.

Obtain Continuing Education Credits (CES) / Learning Units (LU), including Health, Safety and Welfare (HSW) when applicable. Registered conference attendees will be able to submit session attended for Continuing Education Credits (CES). Register for the conference today to gain access to all the AIA/CES credit sessions.

Saturday, April 1, 2023

9:00am-10:30am

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Pedagogy: Holistic Knowledge

Moderator: Marcelo López-Dinardi, Texas A&M University

Product Design in the Desert Common: Methods and Practice

Elpitha Tsoutsounakis, University of Utah

Abstract

Approximately 13% of the land area of the United States is protected in some way by formal designations through state or federal government. Each designation implicates specific forms of management and interaction with ecological systems and community members. Current strategies rely on a complex network of NGO’s, government bodies, and Sovereign Tribes, often with disparate or contrasting needs, values, and desires. This paper will discuss a platform in design education that finds common ground for these groups to collaborate through design research and practices. Design methodologies organize and mediate this complexity and foster free exchange of ideas, knowledge, and values. The platform is unique in that it moves beyond traditional science partnerships, and seeks to mediate the divide between academic and community scholarship. This paper will discuss methods of the the studio for commoning design in public lands.

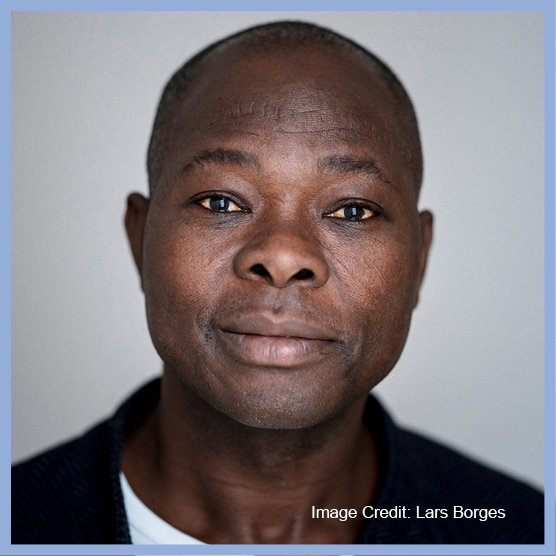

New Faculty Teaching

Shawn Bailey, University of Manitoba

New Faculty Teaching

Abstract

Shawn Bailey is an Indigenous Scholar and practicing architect at the University of Manitoba, where he is a faculty member in both the Faculty of Architecture and the Price Faculty of Engineering. Raised in Lake of the Woods, Ontario, Shawn has a deep understanding of the natural world due to his immersion in a rich natural environment, which has given him a strong connection to the land and an understanding of the interrelationships within it. Shawn’s research and teaching approach is based on a dedication to understanding how traditional Indigenous Knowledge can be integrated into practice and education, fostering community and finding meaningful ways to include the natural world. He is particularly interested in how Indigenous teachings can provide new perspectives on sustainability through ideas of interconnectedness. He focuses on community-centered design processes and methods, fostering connections to the Land by incorporating Indigenous Knowledge through discussions, teachings, and ceremonies. In his design studios, Shawn closely collaborates with Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Cultural guides to re-embrace land-based principles and to develop an animate understanding of the Land. His experiences with Indigenous Knowledge have shaped his approach to teaching design. The design studio provides opportunities for students to form connections with Indigenous communities and to discover how they each can reveal the positive impact that architecture can have on individuals and society. Shawn has led a new approach to design for students and the community at the University of Manitoba by creating Five Decolonizing Design Paradigms, which embraces the Ojibway concept of Mino-Bimaadiziwin, meaning “the good life for all nation’s people”. His approach centers on the Land as a form of pedagogy, Indigenous Knowledge, and process-based experiences through exploration, contemplation, and reflection.

Building Equality(ies) in Architecture North – BEA(N)

Shannon Bassett, Laurentian University

Diversity Achievement Award – Honorable Mention

Abstract

I continually strive to promote and advance equity, diversity and to advocate for and give voice to those who have not been part of architectural discourse or who have been marginalized. I continue to be committed to engaging, promoting and stimulating diversity through my Community Service, Teaching and Research. Architecture School and Community Service As co-founder of BEAN – Building Equality in Architecture North – https://www.beanorth.com, I co-created a collective comprised women architects and architecture students who work and study in Northern Canadian Communities. This platform continues: the sharing of resources; the dissemination of women’s work through lectures, symposia; and the facilitation of mentoring between students and professionals. The BEA(N) Advisory board, which I am the Chair, includes Indigenous and Inuit women architects as critical voices. Architectural Education I have integrated both Indigeneity and Indigenous teachings into the architectural curriculum.Included is land-based learning and building on my established practices of integrating landscape, ecology and symbiotic relationships to the Land into the curriculum, collaborating with our Indigenous Elder and Knowledge Carrier. Women’s voices are included in my Writings in Architecture class/Cities by Design class. I designed a new Urban Design course “Urban Settlements and Morphology” to be taught in the core curriculum which introduces pre-settlement patterns and the decolonization of cities.This builds on my already established global education in China and India where I have led numerous studies abroad programs and in-country studios with students, introducing them to diverse non-western perspectives through collaboration with local schools. Research – My advocacy for diversity in architectural education has been disseminated through numerous presentations and published works. I am a multi-million dollar grant which engages researchers and citizen groups and cities across Canada on Quality in the Built Environment in Canada by “seeking equity, social value and sustainability.” Our site teamadvocates for our remote Northern communities.

Site, Matter, Ecology, and Indigenous Storywork

Adrian Phiffer, University of Toronto

Creative Achievement Award

Abstract

Design Studio 2: Site, Matter, Ecology, and Indigenous Storywork is the second studio in the Master of Architecture core studios sequence at the University of Toronto. This application covers the first two iterations of the studio: 2021 Winter Semester taught exclusively online, and 2022 Winter Semester taught online for the first three weeks and in-person for the reminder of the semester. Developed in partnership with the citizens of the Ho:dinösöni / Six Nations of the Grand River and other numerous Indigenous advisers, Design Studio 2 engages the core graduate design education in the process of Truth and Reconciliation in Canada by answering the Calls to Action outlined in the Wecheehetowin ‘Answering the Call’ at the University of Toronto. Pushing through various preconceived ideas and anxieties related to Canada’s colonial past and relationships to the Indigenous First Nations – a blind spot in architecture academia – the studio explores alternative forms of design pedagogy that privileges Indigenous worldviews and utilizes architecture thinking as means of reconciliation. Throughout the semester, the students take the necessary time to listen and learn Indigenous teachings, histories and worldviews; participate in workshops, presentations, and talks geared towards an open and relational understanding of the environment; and reflect and interpret the learning experiences via architectural proposals. The final studio projects are developed in response to real site, program and cultural demands. The results make an impact in the life of community. While the first project of the semester is similar in both iterations of the studio, the second project is different. In 2021, the students designed a cultural centre on the site of the first residential school in Canada – the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School built in 1832. In 2022, the class developed ideas for a seedbank and greenhouse at the Kayanase Ecological Restoration.

9:00am-10:30am

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Design: Common Commoning

Moderator: Maryam Eskandari, California State Polytechnic U., Pomona

The Commoning of Architectural Representation

Gregory Corso & Molly Hunker, Syracuse University

Abstract

The notion of the commons invites us to reconsider the ownership of architectural space. But is this reconsideration limited to the physical space of architecture? How can we think of ideas of ownership, stewardship, and access through the lens of architectural representation? Can we cultivate an audience for architecture by divorcing the representation of it from both the internal motivations or singular point of view of the designers and the disciplinary baggage and esoteric values often embedded in architectural representation? By viewing the idea of the commons not through physical space but through the representation and imaging of the built environment, we may see possible opportunities for building a more universal and inclusive relationship to design. This paper explores these questions through the lens of a recent exhibition by the authors entitled [TITLE REDACTED], presented at the [GALLERY REDACTED]. This exhibition presents four public space projects (three built and one unbuilt) by [AUTHOR NAMES REDACTED] through the many points of view of a diverse group of 12 visual and non-visual artists from outside of the discipline of architecture. The exhibition consists of 8 visual (drawing, painting, video art) and 4 written (short stories, poetry) contributions, each representing one of the four selected projects by [AUTHOR NAMES REDACTED] without a specific directive. The work presented in the show privileges external perspectives as a way of exploring alternative interpretations and unfamiliar framing of the projects. By “outsourcing” this representation, the exhibition is intended to distill multiple, parallel perspectives and narratives of the featured public spaces, both critical and celebratory, therefore dissociating it from any singular understanding of the authors, towards something more pluralistic. Additionally, the exhibition presents architectural ideas in more familiar and accessible vehicles (comic books, short stories, etc), creating new entry points for a non-architect public. Ultimately, by packaging the projects in extra-disciplinary instruments that are authored by others, the exhibition challenges existing notions of authorship, audience, and access in architecture. We as architects have significant ambitions relative to what we feel is possible through good design, but none of it matters if we cannot build an engaged audience and bring a multitude of productive perspectives to the table. This paper intends to look at how the current insular nature of architectural representation can be challenged with alternative modes of communication and representation to both extract different readings of architecture and also reach a larger, more general audience. In so doing, the narrative around architecture becomes less top down, allowing for new voices, and a greater number of them, to participate.

Cover the Grid

Erik Herrmann & Ashley Bigham, The Ohio State University

Abstract

Cover the Grid is a temporary installation on a timeworn but treasured community lot in North Lawndale, a neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side. Fabricated as part of the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial the mural leverages cutting-edge tools, low-impact methods, and community engagement to create a public space with modest resources and a low ecological footprint. Cover the Grid is not a final park design but rather a prototype, a temporary graphic testbed for experimentation as the neighborhood considers the long-term future of its park. The installation provides an important transitional landscape as fundraising efforts continue to repair the existing basketball court and acquire permanent infrastructure. Installed with GPS-guided robots and temporary marking paint, Cover the Grid suggests a new model of rapid spatial prototyping that invites community-based debate and engagement into the design process with the help of embodied representations at a 1:1 scale. The project’s site, Bell Park, is an existing community lot situated at a critical crossroads of civic connections at the scale of the block, neighborhood, and city. Physical links include an informal but popular pedestrian corridor (block), iconic Ogden Avenue (neighborhood), and the elevated Pink Line rail (city). The design process focused on how the park might be reorganized to maximize interaction between these key civic connectors and provide assets for their diverse constituencies. The conceptual design phase included community outreach and collaborative workshops with students from a high school design camp. Planning began in earnest in the spring of 2021. The design was finalized in late summer and installed in one week. The project utilized a robot designed to install sports fields, to mark the pattern on the asphalt lot. The sports marking paint is water-soluble, non-toxic, and VOC-free. The low-impact installation method meant the park was never closed during installation, with local children often testing patterns only a few hours after they were painted. As a prototype, Cover the Grid suggests new possible programming for city-owned infill sites throughout the West Side. On a local level, Cover the Grid has served as a testbed for spatial experimentation not by designers, but by residents. The colorful modular design has been retrofitted with an outdoor furniture system that adapts to events including basketball tournaments, music concerts, and spoken word performances. Lessons learned from this experimentation will inform future park planning. Looking beyond the immediate project, Cover the Grid suggests a novel model of spatial prototyping that should be considered for larger, more permanent projects. The use of in situ 1:1 representations provides possibilities for engagement and self-actualization for the community that abstract drawing and categorical renderings often fail to provide. If we shift our focus to advanced tools in architecture from the realm of the lab and into the larger world, how might rapid spatial prototyping offer more opportunities for direct engagement in the design process? How might we rethink the notion of “mock-ups” in architecture to better communicate a project’s intentions and possibilities to the community?

CloudHouse Shade Pavilion

Iman Fayyad, Syracuse University

Faculty Design Award

Abstract

CloudHouse is a shade structure that uses curved-crease folding, a zero-waste geometric construction technique that creates rigid surfaces out of standard low-cost sheet material. This project was executed in collaboration with the City of Cambridge’s Community Development Department to provide shading to a low-income neighborhood park that has a deficit of tree canopy coverage. It serves as part of the “Resilient Cambridge” program that seeks to educate the public on urban heat islands and the urgency of climate change, and to activate underserved open spaces with pubic art. It was important that the pavilion deploy construction methods that use recyclable material, produce little to zero waste, and require limited skill and cost in assembly. The specificities of the geometric and material constraints were integral in addressing the social and environmental impact of this structure while simultaneously advancing disciplinary practices in construction and form-making. This project is part of a larger research inquiry into formal and geometric techniques which interrogate why and how certain materials, building types, and construction methods are confined within exclusive social and political domains. I am committed to advancing the discourse around architectural geometry by exploring how it can serve as interlocutor between the often disparate issues of societal needs, culture, environment, material, and formal explorations. I believe that knowledge of geometric behavior can allow us to build more cheaply and consciously, to accommodate subjective experience in the design process, and to make architecture a more inclusive and participatory act. This structure is a prototype that tests the effectiveness of this technique in three avenues: low cost, ease of construction, and formal innovation made possible by the former two variables. More importantly, the technique introduces a new appetite for architectural vocabularies borne out of zero-waste design strategies, emphasizing sustainable building practices through the elimination of material off-cuts.

The Bronzeville Action Coalition: A Model for a Distributed Urban Commons

Neeraj Bhatia, California College of the Arts (CCA)

César A. Lopez, University of New Mexico

Faculty Design Award – Honorable Mention

Abstract

The numerous vacant lots in Chicago represent urban inequity that is propelled by—and a symptom of— property ownership and redlining. As more residents live in precarity, the urban commons, wherein a shared resource is collectively managed and governed, takes on a new importance. By sharing resources, residents can have access to more resources without economic burden. While domestic commons (or communes) have historically offered meaningful forms of agency to residents, they have struggled to become a widespread model for living. This is not surprising, as communes rely on an intimate scale of decision making which is eased through having a more homogeneous group of residents. This design-research project addresses these issues by decentering the commune into an urban commons that could occupy numerous vacant publicly-owned lots in Bronzeville, Chicago. As a network of sites, additional scales of sharing resources and forming resilience are generated. The forms of solidarity that the commons promote already exist in Bronzeville through a range of inspiring organizations and initiatives focused on mutual aid, resource sharing, and skill building. This design intervention speculates on how these various initiatives can assemble a network of sharing that focuses on four key resources—food, making, ecology, and care—that would provide more local control to residents in crafting their own ways of life. The Overton site features one of these interventions: a meeting space for the community. The design is positioned as a malleable framework that utilizes a series of curtains for residents to curate an array of interactions—from intimate to collective gatherings. The fabric enables transformations of the space that acknowledges the evolving practices and values of commoning. Through this decentralized model of sharing, new forms of solidarity can empower residents to take action on the available city. Scope: Research Newspaper, Urban Design Proposal, Pavilion prototype, Event curation

9:00am-10:30am

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Society + Community: Social Collectors & Re-Imagining Typologies

Moderator: Dragana Zorić, Pratt Institute School of Architecture

[Un]common Ground: Co-Creating the Vision for the city’s Ground Floor

Julia Grinkrug & Christopher Austin Roach, California College of the Arts (CCA)

Abstract

What do we share in common among each other and what are the [un]common experiences and identities that are needed to preserve diversity of perspectives? How can a common ground be established in pursuit of uncommon needs that mark the divergent missions of various interest groups? Is there even a possibility for the “commons” in our radicalized, alienated, co-opted, gentrified, and post-truth world? These are the questions that occupied a group of academic practitioners from Urban Works Agency at California College of the Arts through a series of courses that revolved around the enigmatic topic of the commons. In this paper, we will unpack the most recent investigations and discoveries that emerged from three consecutive studio courses that focused on reimagining the ground floor of the city. At the conception of this three-year project, we were searching for overarching principles or codes for commoning, learning from worldwide precedents where public space was generated as a common good. As the research evolved in close dialogue with community partners, it became more and more clear that the notion of common good as a homogeneous abstraction is a fiction, just like the notion of a generic “public”. Instead, the commons should be seen as an amalgamation of agonistic desires, practices and capacities that is meaningful only as long as it maintains its heterogeneity. According to Stavros Stavrides, the commons “is a relation of people with the conditions they describe as essential for their existence, collectively” (Stavrides, 2016). As such, the commons is a continuously evolving entity that defies delineation or fixation. As theoretical as it sounds, this statement is a tangible reality for people on the ground, navigating the “politricks” (as they call it) of municipal and market-driven legislations and figuring out the common ground among their own divergent agendas. As Ms. Margaret Gordon, a long-term activist and our studio partner from West Oakland , put it – the only way to achieve equity benefits for the community is through “intersectional coordination”. The design-research described in this paper builds on the extensive previous research of the commons in the works of Sheila Foster, Stavrides, Gruber, Fortier and others, which described the concept of the commons as a theoretical framework, political ideology, social practice and spatial strategy. Importantly, this project was differentiated by being applied to the investigation of the ground floor of the city as a distinct spatial entity and urban system, offering new interpretations for the “social infrastructure” (Klinenberg, 2018) and what we called the “community organization of land”. Thus, our applied research contributes to the current discourse through a uniquely grounded, community-generated response to the question of commons. Imaginative and speculative student projects and engagement tools that were co-created in collaboration with community partners did not necessarily produce fully-resolved solutions, but rather design provocations that dared to rethink the baseline value system, tackling the fundamental notions of ownership, property and governance in access to power and representation in city making processes.

Material Commons

Brent Sturlaugson, Morgan State University

Abstract

On March 13, 2019, Mayor Catherine Pugh climbed into the cabin of a hydraulic excavator and began carving into the two-story façade of an Italianate rowhouse in the Druid Heights neighborhood of Baltimore. In a city of more than 30,000 vacant properties and a population that continues to decline, Mayor Pugh’s publicity stunt represents one of many efforts to address vacancy without confronting its underlying causes or lingering effects. Druid Heights, like many neighborhoods in Baltimore, suffers from the cascading effects of racially discriminatory policies that prevented the accumulation of wealth and power through individual property ownership, ultimately leading to high rates of poverty and vacancy. Despite Mayor Pugh describing the stunt as “very energetic” and “ready to do more,” the underlying issues remain unaddressed.[1] Alongside the racialized disinvestment in neighborhoods like Druid Heights, Baltimore also hosts a rich history of cooperative enterprise and collective ownership that forges a different path toward the accumulation of wealth and power among historically oppressed communities. From the Black mutual aid organizations documented by W.E.B. Du Bois in the 1900s to the radical collectives formed by feminist socialists in the 1970s, Baltimore nurtures a range of what J.K. Gibson-Graham refer to as “diverse economies,” which, in recent years, include a growing number of community land trusts and reclaimed material stocks.[2] Drawing on the diverse traditions of commoning in Baltimore, in this paper I argue that the deconstruction of vacant buildings in historically disinvested communities can be leveraged to reimagine property and labor relations—and their attendant spatial configurations—toward a more socially just and ecologically viable future. The paper consists of three parts. First, I contextualize vacancy in Baltimore by analyzing the policies and practices that created zones of racialized disinvestment, in what Lawrence T. Brown calls the “Black Butterfly.”[3] In these zones, residents lack access to adequate resources and services, rendering the private accumulation of capital ineffective in the creation of wealth and power. Second, I argue for a reconceptualization of prosperity in neighborhoods experiencing high rates of poverty and vacancy through systems of collective ownership and cooperative enterprise. Building on Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s study of Black cooperatives and Andrea J. Nightingale’s call to focus on “becoming in common,” I highlight the ongoing work of community land trusts and reclaimed material stocks in Baltimore and situate these efforts within a broader context of collective organizing.[4] Third, I offer a framework for rightsizing a prototypical block through targeted deconstruction and material reuse in the creation of a neighborhood commons.[5] The framework unfolds in a boardgame, called “Material Commons,” that simulates redevelopment and promotes agency among affected communities.

Community Resilience Hubs: Social + Emergency Infrastructure in Detroit’s Neighborhoods

Ceara O’Leary, University of Oregon

Abstract

In Detroit, community hubs are emerging as essential sites for a myriad of services and activities contributing to both short term disaster response and long term community resilience. Community hubs have long been spaces of convening, information sharing, tutoring and other elements of social infrastructure for all ages. Increasingly, hubs are intentional spaces for cultural production and community cohesion, contributing to strong neighborhood networks, and also sites for disaster response, including heating and cooling in cases of emergency as well as provision of health supplies and food distribution. This paper documents an ongoing research-based project focusing on existing community resilience hubs in two neighborhoods in Detroit as sites for cultural production, youth activities and social infrastructure as well as opportunities for emergency preparedness and building performance to enable function in times of crisis. This work includes study of hubs in other cities and considers the link between cultural and climate resilience and how community hubs are spaces for both. This project is part of a larger collaborative neighborhood planning process that centers community resilience and health equity outcomes, focusing on access to resources in Detroit neighborhoods of varying density. This includes visions for current and future community hubs that contribute to resiliency.

9:00am-10:30am

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Urbanism: Urban and Territorial Pedagogies

Moderator: Perry PJ Yang, Georgia Institute of Technology

Collective Domestic: Theorizing the Intermediate Commons

Omar Ali, Tulane University

Abstract

This paper introduces research from a special topics seminar that explores the incorporation of collective intermediate space (also referred to as gray space and the intermediate commons), as a possible alternative to the isolated condition of most housing design arrangements in North America. Gray space is most easily understood as the transitional intermediate space prior to entering or after exiting a domestic space to the public domain. These spaces often blur the line between public and private space; inside and outside; formal and informal; are truly multi-functional and can be defined by the end user. One of the primary objectives of this course is to understand the historic and vernacular foundations of housing and architecture’s relationship to public space and the commons through its various conditions and to grasp how this relationship has changed across various contexts over time. This research aims to have the following impact. (1) To visually analyze and assess spatial challenges and opportunities within three vernacular types. This analysis evaluates the social and material qualities of space provided within the domestic type, and the clarity of its connection to the intermediate commons. (2) To examine the local context of these types and how architecture has had a role in cultivating the shared cultural identity and community of the place. (3) To expand upon the use of visual research and visual communication to tell a cohesive narrative of place. In short, the intermediate commons can be understood as spatial, architectural, and tactile, but must also be recognized as a space for social innovation and radical openness. Collective Domestic: Theorizing the Intermediate Commons asserts that the sequestered and heteronormative condition of current developer-driven housing trends can be countered through the proper activation of gray space in housing.

Commoning the Urban Residual: Making the Case for clandestine Social Infrastructure

Robert Sproull, Auburn University

Abstract

“Conventional hard infrastructure can be engineered to double as social infrastructure.” Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People1 Hard, or critical, infrastructure doubling as social infrastructure is not new. It has been a useful strategy for centuries. Projects with these overlapping programs usually spring from a handful of different design scenarios. They’re often built initially as hard infrastructure and converted to social infrastructure at the end of their useful life, (like New York’s Highline or Johannesburg’s Zeitz Museum). They can be modifications of existing ‘still-in-use’ critical infrastructure projects (like BQE Park in New York or Klyde Warren Park in Dallas). Lastly, they can be designed as overlapping critical and social infrastructure from their conception (as with Copenhill in Copenhagen or the Ponte Vecchio – at least in its current form). One method for establishing critical/social infrastructure is through enhanced public works projects. In this scenario, hard infrastructure projects are injected with additional program that adds a social element to the final built version. Often, this “thickening” of the program can face uphill battles related to increased funding, red tape, or public backlash, and the ‘extra’ program is often the first element to be ‘value-engineered’ from the project. However, commoning, (the grass roots collaborative effort of a community to meet its needs), can be a viable alternative method for the creation of these enhancements. There already exist precedents of critical/social infrastructure evolving out of the commons. Chicano Park in San Diego and FDR Skate Park in Philadelphia are lasting examples which are directly related to residual space left after interstate highways were built2. This paper will present ongoing research related to the overlap of critical and social infrastructure specifically as it relates to atypical methods for their creation. Additionally, it will present a design course that explores opportunities to create social infrastructure in the overlooked spaces left by the construction of critical infrastructure. It will discuss this on a global level through case studies from around the world and a local level from a series of student design projects situated in a mid-size southern U.S. city. In these projects, residual spaces, (the highway right-of-way and surrounding neighborhood), become the setting for projects that can tap into the commons and be re-imagined as social infrastructure. The work springs from the caveat that these residual spaces can be a place of social interaction when conceived of appropriately. The students’ work optimistically approaches these spaces as ‘usable’ instead of a forgotten zones of disjunction found so often around large-scale infrastructure. In this new scenario a reinvention of overlooked land is reconsidered as public gardens, settings for large scale land art projects, and parks. The paper begins to present a case that for some social infrastructure projects, the most ideal manner of conceiving and creating them is through the commons rather than as a public works project. The effectiveness of organic community investment inherent in this method establishes a more enduring presence for the people and places they serve.

HELIOStudio and the Energy Commons: The Third Generation of Energy Landscapes

Christine Mondor & Nicolas Azel, Carnegie Mellon University

Anna Rosenblum, evolveEA

Robert Ferry & Elizabeth Monoian Land Art Generator Initiative

Abstract

Renewable energy technologies are transforming our landscapes with distributed installations that have the potential to unseat centralized corporate and governmental power and return control to communities and individuals. After centuries of consuming “buried sunlight” we are harnessing the dynamic forces on the earth’s surface, shifting from Noorman and DeRoo’s “second generation” of extractive energy landscapes to the “third generation” energy landscape of decentralized production. When production and consumption become local, new interdependencies arise between the physical environment and spatial practices as energy is no longer organized by public authorities but as a public resource able to be managed locally through commoning practices. HELIOStudio at Carnegie Mellon University speculated how solar technologies and the (re)emergence of distributed energy infrastructure will reshape the reciprocal relationship between landscape, urban form, and spatial practices. What new rituals and practices might arise if the means of production and consumption were closed within a site, a neighborhood, or a city? HELIOStudio examined the urban structure of energy landscapes and the community structure of an energy commons to advance social, environmental, and economic justice. It is partly informed by the work of the nonprofit Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI) and also engaged a number of other technical experts, including community experts, throughout the semester. The studio outcomes are informing policymakers, planners, and architects of the potential of new energy landscapes. HELIOStudio succeeded on three levels: it generated new knowledge about how utility scale urban solar can be integrated into an urban environment, it provided direct benefit to the participating community stakeholders, and provided a rich tapestry of collaborative experiences preparing the students for practice. The paper will share three streams of studio investigation: PERSONAL ENERGY, LOCAL ENERGY, and URBAN ENERGY. Like most infrastructure, energy is mostly invisible. PERSONAL ENERGY visualized the human dimension of energy and connected lived experience with the invisible flows that often characterize energy technology and policy. By examining how distributed technologies are applied to urban drosscapes, LOCAL ENERGY investigated how solar technologies might inspire new urban practices and engagement with the land, ranging from performative inventions to ritualized solar installations. Through a series of design proposals, urban analyses, and community expert engagement, URBAN ENERGY investigated possibilities for industrial-scale production within the confines of the city and examined the technostructure of production and consumption.

Subjective Waters

Curry Hackett, University of Tennessee–Knoxville

Creative Achievement Award

Abstract

The Subjective Waters studio studied Black relationships with water to interrogate its role in shaping power, place, and cultural production in the built realm. Students were invited to interpret water not only as a liquid or a geographic feature, but as a complicated milieu of signifiers entangled with Black spirituality, mythology, joy, agency, mobility, historic oppression, and death. Historically Black territories with adjacencies to water, such as New Orleans and all-but-erased “Bottom” neighborhood in Knoxville, served as pretexts for envisioning fluid and “slippery” spatial conditions. Throughout the semester, the studio employed a variety of media, especially collage, to inspire emergent strategies of practice and collaboration. Exercises gradually increased in scale from the object/individual to the urban/collective, while incorporating topics such as hydrology, water urbanism, and placekeeping. The studio consisted of three projects, each using the previous exercise to shape collaboration and partnering strategies, form-finding, and research. The final project aggregated work and ideas from the semester to propose a new, “semi-speculative” territory. Work in the Subjective Waters studio was collectively produced by Amanda Bock, Alexa Castillo, Marlow DeGraw, Eleanor Fryer, Winn Gramling, Brock Henderson, Nick Kohlsedt, Margaret Marando, Mason McMullen, Katherine Murphy, Caleb Nutt, Emma Powell, Gabriel Stimpson, and Abby Thompson.

9:00am-10:30am

Special Focus Session

1.5 LU Credit

Presenters:

Emily Grandstaff-Rice, AIA President

Kendall Nicholson, ACSA Director of Research and Information

Andrea Milo, AIA Director of Academic Engagement

Discussion Leaders:

Andrew D. Chin , Florida A&M University

Thomas Fowler, California State Polytechnic University

June Williamson, City College of New York

Session Description

Join us for a guided 90-minute critical conversation focused on the most recent Guides for Equitable Practice supplement, “Equity in Architectural Education”. Aimed at inspiring discussion and organizational change required to achieve equity, diversity and inclusion goals, groups will be lead through prompts developed by project lead Renee Cheng, FAIA, NOMA, DPACSA and her team. Participants will be asked to use tools from the guide to consider different viewpoints, share perspectives, and consider how to keep discussions going in department meetings and studios.

11:00am-12:30pm

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Pedagogy: Equitable Profession

Moderator: Shelby Elizabeth Doyle, Iowa State University

Addressing Othering in Architecture Education: Learning Ethics and Empathy to Find Common Ground

Alexis Gregory, Mississippi State University

Abstract

Empathy and ethics cannot start in the profession but must first be taught in architecture programs to prepare students to find common ground with their peers, clients, and community. However, as Thomas Fisher noted in his important book Ethics for Architects: 50 Dilemmas of Professional Practice, ethics tends to be limited to professional practice courses.[1] Additionally, we are othering our students by giving them project types in their courses that are not familiar to them and that are not part of their everyday experience, as well as having clients who do not look like them. Based on the evolving demographics of architecture students and clients, empathy and ethics need to be interwoven throughout architecture education to begin addressing the othering of architecture education which will help future architects find common ground. Fisher’s book was written over ten years ago, and despite the call to arms established in the book, and his “tools for survival” in the 2008 book Architectural Design and Ethics: Tools for Survival, architecture education is still moving too slowly to address the issues inherent in our profession and society.[2] Recent social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have shined a light on the unethical things that even our most lauded architectural icons have done, yet women and minorities still struggle for equality in both professional and educational settings. Architecture programs that begin to incorporate empathy and ethics, especially using service-learning and social justice, can also help retain the women and minorities who are often lost after graduation. Studies show that a “commitment to promoting racial understanding” through community service and service-learning appeals to women and minorities and as a result these groups are more likely to become involved in architecture.[3] Research also shows that students are more successful and engaged when ethics, empathy, and agency are included in architecture education. Introducing empathy and ethics exercises into architecture education can help open the minds of our students so that they are better able to approach and solve the issues of our current and future environment. Exercises in role-playing, reflections, and pre- and post-surveys foster discussions with students to help them better understand the viewpoints of others as they design architecture for specific clients and to serve their community. Pedagogical examples, student work and feedback will be analyzed in relation to integrating ethics and empathy into architecture education as well to assess the impacts of these ideas and the ability to reach common ground. Issues like lack of empathy from faculty-to-student, student-to-student, and student-to-client/community partner will be discussed. The methodology used in these design studios will also be presented and the results of the explorations will be shared.

Research-Build: Biomaterial Invention through Design Studio Pedagogy

Kyle Schumann, University of Virginia

Abstract

Academic design-build work provides an incredible opportunity for students to experience hands-on construction and see their work jump from the drawing board to reality. However, the inherent complexity and compressed timelines of these projects typically limit opportunities for material experimentation and invention, instead biasing detailing and construction with proven conventional building systems for timely delivery of a project based on client and programmatic needs. At the same time, architectural innovation in academic scholarship is increasingly confronting technological and material needs necessitated by the climate crisis. This paper presents a research-build model via a studio that shifts the emphasis from program and client to material invention and experimental fabrication. The studio began with a series of physical fabrication exercises and material explorations, culminating in the design and construction of an experimental biomaterial pavilion that pilots three building systems: a double-layered woven bamboo wall with CNC-milled joinery and a shade canopy of thin bent lumber strips, both sourced from campus landscaping waste, as well as a façade of custom paper pulp shingles made with campus paper and wood waste. Salvaging material from the local environment and waste streams serves to improve equity and access to material — teaching students that good design does not necessarily demand expensive materials — and as an environmental strategy, asking students to consider the lifecycle and impacts of the materials with which they are working, and to design for end of life decommissioning.

Critically Engaged Civic learning: How Graphic Design can Become a Bridge Between the Classroom and the Local Community

Claudia Bernasconi, University of Detroit Mercy

Abstract

This paper discusses outcomes from a collaborative project between the School of Architecture and Community Development at University of Detroit Mercy and the LIVE6 Alliance, a Detroit non-profit organization focusing on neighborhood revitalization via placemaking and engagement with small businesses. A graduate graphic design course was offered in Winter 2020, and provided an opportunity for architecture students to interact with local community members and business owners to brainstorm ideas about identity, place, and economic development. The engagement process began with small group meetings between students and owners of six local business, ranging from café stores, bars, event spaces and apparel shops. Student teams worked with the community partners during the semester to gain understanding on priorities, aspirations and identity of the local business, and applied knowledge built in the classroom about graphic design to test alternative branding design ideas. Proposals ranged from signage design for the storefront, environmental graphics for the store and facade, packaging ideas for products, logo design, and business card design, as driven by the needs of the selected business. Through an iterative and open-ended process revolving around frequent conversations and concept proposals, students learned to interpret key identity traits of the businesses, and to acknowledge the values businesses bring to the urban corridor. The pedagogical model of the course is founded in the recognition of the need to surpass prejudiced and stereotypical approaches towards underserved communities which lead to the definition by privileged groups of the needs of underprivileged minorities and the framing of such needs as deficiencies (Mitchell and Humphries, 2007), and aligns with the concept of Critically Engaged Civic Learning (CECL), a revised form of critical service-learning recently coined by Vincent et al. (2021). At the center of CECL are increased awareness of civic agency, and better understanding of the community and workforce preparation (Vincent, et al., 2001). Embracing a CECL approach in the course helped students connect with the community and understand perspectives of local businesses owners, as well as become more aware of their design agency as co-creators. The course structure allowed students to strive for a form of co-production and co-authorship, as a way to decolonize the process of design and go beyond default minimalist design approaches that often perpetuate potentially gentrifying graphic languages. The process fostered a deeper understanding of branding as a defining way of expressing values of individuals, communities and places, and spurred students to recognize the crucial ethical component of graphic design. Additionally, the loosely coordinated collective work of all teams along the corridor, spurred students to understand graphic design as an urban activator and as an element of placemaking at the scale of the neighborhood. Multiple final design proposals were presented to community members in mid-March 2020. The project was interrupted during online and hybrid learning. This hiatus provided time to reflect on lessons learned, including learning outcomes for students and community perceptions, as well as future directions for the collaboration with LIVE6 Alliance towards a student learning that is centered around the search for a co-constructed design agency.

New Faculty Teaching

César A. Lopez, University of New Mexico

New Faculty Teaching

Abstract

First and foremost, César A. Lopez is a first-generation Mexican American from the México-United States borderland and draws from those experiences in his research agenda and pedagogical approach. As a design researcher, César explores the entanglements between architecture and territory and the politics that dictate them to represent collateral populations and environments in need of agency. His recent work identifies the building and infrastructural typologies that inscribe territorial power dynamics beyond the legal boundary itself. He has published these investigations in journals such as Bracket [Takes Action] and ARQ111 and has an upcoming book, Edges, Exclusions, and Ecologies, with ACTAR Publishers. As an educator, César is a first-generation college attendee/graduate who became an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of New Mexico, School of Architecture + Planning. His teaching focuses on reversing the unilateral effects built environments have on populations to introduce counter strategies that center on new subjects to determine architectural imagination and production. He believes architectural education should empower creativity as a formative experience that coalesces humans, non-humans, and environments. Before arriving in New Mexico, he taught at the California College of the Arts Architecture Division and the University of California at Berkeley, College of Environmental Design. César has practiced professionally in architecture, landscape, and urban design. Until 2022, he co-directed The Open Workshop, where he was a leading designer for several awarded-winning projects published and exhibited on national and international stages, such as the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale and the 2021 Chicago Biennale. In 2020, he was awarded the ACSA Faculty Design Award for the New Investigations in Collective Form exhibition at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. César completed a B.S. Arch at the Texas Tech University, College of Architecture in El Paso, Texas, and obtained his M. Arch from the CCA Architecture Division.

Housing America: Architecture’s Social Agenda at the Center of Pedagogy

Tricia Stuth, Ted Shelton, Clayton Adkisson & William Rosentha,

University of Tennessee-Knoxville

Housing Design Education Award

Abstract

Housing sits at the crux of numerous economic, political, and environmental concerns surrounding social justice in the United States. Where and how people live has profound implications for both cities and individuals. On the urban scale, it affects, for example, the efficiency of municipal services, tendency to sprawl, and what forms of transportation are viable. For individuals, it affects economic security, access to employment, quality of education, and even health outcomes. Further, in the United States, housing is more politically charged and more strongly tied to histories of racist and classist policies and sentiments than any other building type. This course brings these complex issues into the heart of the professional architectural curriculum – the building integration studio. In doing so, it seeks a “complete integration” of the architectural act rather than one in which some (social, historical, ethical) issues are muted in favor of a focus on (technical, performative, constructive) others. It also endeavors to create a required reckoning that confronts students with questions of architecture’s culpability for social injustice and agency in the cause of social justice. Rather than placing such uncomfortable but critical issues in an elective course, this course brings them to the fore in what is indeed the only section of a required graduate studio bristling with NAAB criteria. Through a myriad of means – films; readings; meetings with a city councilwoman, developers, a neighborhood association representative, public housing residents, site staff, and property manager; presentations on the history of US housing and the role of zoning and housing policy in de jure segregation – the course illuminates a constellation of concerns that surround housing in the US. While we certainly cannot expect student proposals to address, much less solve, all of the problems presented, they will be richer and more engaged for having looked.

11:00am-12:30pm

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Design: Making New Rules: Zoning

Moderator: De Peter Yi, University of Cincinnati

Finding Common Ground: Reimagining Suburban Housing and Public Space

Omar Ali & Nimet Anwar, Tulane University

Abstract

Finding Common Ground is a speculative project for reimagining the suburban and exurban conditions of North America. The project reexamines the idea of single-use zoning and the single-family detached housing type. Local land use regulations that have mandated the single-family house type on large lots should be replaced, in favor of medium-density housing that is built by right- without zoning variance. This project speculates on the potential form of the suburb through testing these ideas at the smaller scale of four typical suburban blocks. The resultant transformation pilots larger civic minded projects, a higher density of housing, privileges the pedestrian experience over the car, and enables a focus on cultivating a shared collective experience over the current isolated condition of the single detached house on a single-zoned lot. The thesis of this project is executed by pairing typical adjacent lots into double lots and rotating the orientation of the housing from north-south to east-west, to make the most of the double-wide properties, and to have an effective orientation regarding passive energy systems. This subtle change in the orientation of the housing footprints and the use of the auxiliary laneways emphasizes the human experience over that of the car, and fades the literal manifestation of lot lines in favor of a more shared experience between neighbors. The newly established public datum at the ground level which extends beyond the typical boundaries of front, back, and side yard, in exchange for a more public common ground. The ground level is activated by more operative commercial frontage that engages the street as well as the mid-block shared common spaces (previously laneways), and the injection of public programs that enable an overlap of varied publics, beyond simply the residents of the neighborhood. By diversifying the ground, homeowners have a spectrum of income levels due to more income generating opportunities that offset the cost of homeownership. Social amenities are integrated into the project by implementing a series of large-scale social condensers that fulfill the need for sheltered public and accessible space, and are a commons for civic engagement. Finding Common Ground is more broadly about the need for rethinking the exclusionary and constrained idea of single-family zoning. Missing middle housing is an evolution of zoning codes to include a more diverse range of housing types in suburban neighborhoods to provide affordable housing for a spectrum of price points. This will inherently build more diversity, allowing for the changing demographics of the suburbs, and will lead to more walkable neighborhoods. Middle ground housing is tuned to the smaller scale of the neighborhood, and emphasizes space over maximizing units and financial return. By introducing a variety of housing types to the suburbs, the forms of exclusion such as fences will be minimized, if not eradicated completely, in return for a more collective and shared experience. Through the density and clustering of middle ground housing, space is made available for larger civic minded projects to serve as cultural catalysts for change in the city.

Non-Conforming Housing – Housing the Working Class

Dennis Chiessa, University of Texas at Arlington

Abstract

As cities struggle to provide enough adequate housing for their citizens, there is a need to develop new ideas and typologies that address the housing crisis directly. Growth in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex[1] continues to provide challenges in addressing housing shortages[2], particularly for cost-burdened communities and those in danger of gentrification, displacement, and/or chronic homelessness[3]. This project presentation focuses on the analysis of the housing stock and context of a neighborhood in Fort Worth, TX that informed design proposals for infill housing. The central question driving the project was: How can we design housing to increase density in a single-family urban neighborhood with an aging housing stock, a history of community marginalization, and inadequate zoning that deems many properties as nonconforming and/or unbuildable? Understanding the housing stock of the neighborhood is critical to developing appropriately scaled and appropriately priced housing to meet current and future demands while slowing down displacement and creating minimal disturbance to the urban fabric of the neighborhood. The analysis is two-fold and was conducted at the scale of individual lots and houses. Our research found that although most of the land is zoned for 5000 square-foot single-family lots, there is a sizeable number of duplex housing units that are either grandfathered in or clandestine[4]. There are also significant numbers of vacant lots that are non-conforming due to minimum square footage requirements. At the building scale, we documented, through drawing and models, ten existing homes within the study area that range in size, style, and location to create a catalog identifying key architectural elements commonly found in the neighborhood that define the character of the built environment. We found that scale/size, roofs, porches, and parking conditions are the primary determinants defining the character of the historic housing stock and the overall cohesiveness of the neighborhood. Historically, the community (project site) provided the workforce for the Stockyards and the meatpackers of Fort Worth and was segregated along racial lines, a fact that is reflected in the housing stock. Our research shows that parcels of land were subdivided almost one hundred years ago to create two 2,500 SF lots from a single 5,000 SF property. This allowed for the construction of multiple houses, typically shotgun houses, on a single lot to provide housing for the working class of the stockyards. These smaller lots are no longer buildable lots according to the current zoning ordinance. This project argues that small-scale houses and lots were common and can continue to be a viable solution for current housing needs. This study identifies other nonconforming lots in the neighborhood to use as sites for the new infill prototype houses. Additionally, the housing prototypes were developed addressing the common characteristics analyzed in the existing buildings. The work attempts to prove that these ‘nonconforming’ lots are viable options for reintroducing smaller scaled, affordable houses that cause minimal disruption to the existing urban fabric. The set of new house prototypes can be strategically deployed to increase density and provide more affordable housing options.

Southside Survey: Alley Houses for South Bethlehem

Wesley Hiatt, Lehigh University

Abstract

Southside Survey is an ongoing research, design, and advocacy project that asks how architects can imagine novel density solutions within historic contexts that are reconciling intense development pressures with the politics of change. Born out of contemporary housing debates in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, this project proposes a place-specific densification model through the revival of the “Alley House,” a regional housing type common in the 19th century that was effectively outlawed during the mid-century trend of suburbanization and single-family down-zoning.1 Home to old Moravian Bethlehem (a UNESCO World Heritage List candidate) and the decommissioned Bethlehem Steel factory (now repurposed as Wind Creek Casino), Bethlehem and the Southside in particular have staked their post-industrial economy on heritage tourism.2 This preoccupation with history also shapes public discourse on the construction of new housing. In a city with a 3.5 percent residential vacancy rate, a recent developer-driven building boom of over 1,000 new units has been met with widespread community opposition.3 “Too tall” and “doesn’t blend in” are common refrains. Appeals to the ineffable qualities that make the Southside “itself,” framed within the rhetoric of historic preservation, often stall or stop development entirely. Southside Survey proposes a density model within this context that mediates between the competing interests of preservation and development. This project works to craft a housing culture that leverages regional building traditions to envision a locally-specific model for accessory dwelling units – the “Alley House.” Found throughout Eastern Pennsylvania, Alley Houses were built on the “back” of occupied parcels to quickly house immigrant workers in rapidly industrializing towns. These improvised homes-on-the-alley were often rented by the homeowner for supplemental income or to accommodate extended family structures. In South Bethlehem specifically, the Alley House was historically instrumental in housing the rapid influx of workers employed by the booming Bethlehem Steel, then the world’s second largest steel manufacturer. In today’s housing crisis, regulatory change is necessary for new Alley House development to be possible, and any new zoning ordinance must be made legible and accessible for community buy-in. Southside Survey works to catalyze this change by positioning design possibility and architectural knowledge as public assets within a specific community. Carried out through three distinct but related modes of work – including a field survey, speculative design prototypes, and on-the-ground activism – this project advocates for regulatory change while re-imagining the traditional Alley House for contemporary use on the Southside.

11:00am-12:30pm

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Society + Community: Food Networks, Traditions & Systems

Moderator: Cathi Ho Schar, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Addressing Food Deserts Through Re-localized Agriculture: Four Design Typologies with Community Engagement for Urban Food System Expansion on Municipal Land

Courtney Crosson, University of Arizona

Abstract

Tucson, Arizona has been a historic passageway and home to a rich overlay of settlement patterns for over 4,000 years. In 2000, archaeologists discovered layers of irrigation trenches below the ground of the city, distinguishing it as the longest continuously farmed landscape in North America. Currently, 18% of current Tucson residents live in food deserts, areas that are low-income and have restricted access to healthy and affordable foods [1]. Despite its agricultural history, recent efforts to relocalize urban food production to meet these local nutritional needs face stern criticism that the city is already water-stressed and cannot afford the irrigation required for food growth. This research investigated the feasibility of expanding the urban food system of Tucson on available municipal land using only sustainable water supplies: passive rainwater harvesting, active rainwater harvesting, and reclaimed water. Working with community partner organizations on city or county owned parcels, four typologies were developed to relocalize food production in food desert areas across the city: river adjacent, urban alley, community garden, and indoor controlled agriculture. The capacity to grow food across these typologies with sustainable water supplies was tested through designs for these parcels in an upper-level design studio course. Through the design process, community assets and needs were assessed for multi-benefit solutions through a series of engagement activities with food cultivators, distributors, and the neighbors surrounding the site. This paper presents the four typological designs, their associated water harvesting and food production capacities, and the community engagement conducted to reach these design outcomes. Ultimately, if these design typologies were implemented across the 711 acres of available municipal land in current food desert areas, over 100% of the nutritional needs of these food desert areas would be met [1]. The work culminated in an outdoor exhibition in a large historic garden in Tucson open to the public to disseminate the research, stimulate conversation, and offer a platform to gather community support around the relocalization of urban food systems. The community garden typology designed as part of this research is currently being constructed by the county and local community food bank.

Slowly but Surely: Chronicle of Springfield’s First Community Fridgezz

Sara Khorshidifard, Drury University

Abstract

Not all tools or normative practices at the hands of architects and designers may align with the call for architectural commoning. Yet, design thinking and skill contributions to building more sustainable, resilient, and equitable communities are conceivable on all levels and scales. One such approach aligns with what is theoretically known as the “mutual aid.” Activist and law professor Dean Spade in his 2022 book Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) defines the concept as the survival work done in conjunction with social movements. Mutual aid is a framework for demanding transformative change, for radically redistributing care and wellbeing, and to ultimately “heal ourselves and the world.”[1] Through a mutual aid outlook, even though with small design acts, architectural contributions to regenerative and redistributive commons-based economies are foreseeable, by putting design to work and the heart where the needs are. Mutual aid in action is the story behind the journey of Springfield’s first Community Fridge. It all began with an electronic message circulated during a peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2021, sharing voices of two city residents who had raised the need for neighborhood fridges due to rising food costs and local food insecurities. The Community Fridge movement has started globally as a grassroots effort to combat food insecurity and food waste. When installed in accessible locations, they are proven to act as vital and identifiable resources for community members to pick up free fresh food and for patrons to donate excess food. Springfield’s Community Fridge project born with the spark from residents Mal Bailey and Chelsy Cantwell grew in partnership with local Citizen Architect Kate Stockton and Sara Khorshidifard, architecture faculty and director of Drury HSA’s Center for Community Studies. The initiative has since gained momentum in the months and year following, and attained resourceful new partnerships such as Drury AIAS Freedom by Design, the West Central Neighborhood Alliance and Urban Roots Farm business as hosts, Better Block SGF through its WeCreate 2022 design competition focus, and the Discovery Center of Springfield with fresh produce donations from its aeroponics vertical gardens. The first neighborhood soon hosting the first Springfield community fridge today has high need for food resources where neighbors will definitely benefit from the project. According to City data, 16.9% of county households are food insecure, an issue highly prevalent in West Central that is amongst poorest neighborhoods. Most recent data indicated 80% of residents as renters, 41.8% individuals and 30.8% families below poverty rates, with 14% unemployment rates and a median income as low as $19,731. Thanks to the collective efforts, unscripted impetus of the mutual aid groups and individuals involved, and funding through donations and grants, the fridge is now on its way in the built stage set for competition in fall 2022. [1] Dean Spade. Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next). Verso Books, 2020.

Communal provisioning and community abundance: Operationalizing Jewish concepts of gleaning through two design projects

Caryn Brause & Madison DeHaven, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Abstract

Each year, more than 10% of the U.S. population experiences food insecurity.1 Historically, many faith-based organizations have focused on alleviating hunger as an expression of their values. As these organizations represent some of the largest landowners in the world, some of their less productive holdings could be repurposed to directly address food justice. In Jewish practice, the biblical literature outlines laws that provide agricultural support in the form of fallen grain and fruit available for post-harvest gleaning.2 Gleaning is one of several practices to address economic precarity; along with gleaning, agricultural rest and debt forgiveness aimed for social, economic, and environmental resets in pursuit of a more just society.3 Two associated projects, Abundance Farm and the Food Security and Sustainability Hub, provide design examples that address food justice by operationalizing Jewish traditions of “the commons.” Abundance Farm is a one-acre food justice farm and outdoor classroom. The project developed through collaborations between three neighboring institutions – a synagogue that owns the land and provides staff, utilities, and programming; a food pantry serving over 3,000 people per year; and an elementary school that incorporates the farm into curriculum. Over the past decade, Abundance Farm has integrated land-based programming into the Jewish community’s ritual life while offering educational programs for the broader community. The Farm has operationalized Jewish concepts of social justice through spatial and design practices. For example, to activate the concept of pe-ah, the design team located a pick-your-own orchard along the synagogue’s street frontage; the orchard repurposes the institution’s front lawn, providing perennial fruits and berries to passersby and those in need. Welcoming visitors to the site, the Help Yourself farmstand provides a highly visual outreach element and kiosk showcasing the farm’s fresh-picked produce. Building on Abundance Farm’s successes, the synagogue purchased an adjacent extant municipal property through an RFP foregrounding community benefit. The design process for the Food Security and Sustainability Hub engaged Farm leadership in visioning both short- and long-term programs proposed in the Community Benefits Statement and concurrent grant applications. Site planning and building design exercises explored the Farm’s expanding mission and services that emerged during the pandemic. Design visualizations provided probes for dialogue about the ways adaptive reuse of the building and remediation of the brownfield site could provide for inclusive future uses including food production and processing, educational and workforce training, value-added business incubation, skill-sharing, and community gathering. In the coming decades, it is expected that more than one quarter of all U.S. houses of worship will close,4 presenting an opportunity to transform these properties in ways that promote positive ecological health and human wellbeing. Indeed, a growing national interfaith movement is already working to provide tools to faith communities so that they can experiment with greater ecological and socially just land stewardship for a wide array of their property holdings.5 While modest in scope, the Abundance Farm initiatives offer design and organizational prototypes that suggest how we might expansively redeploy quasi-public landscapes held by faith-based organizations to advance communal provisioning and community abundance.

Architectural nodes within Chicago’s Urban Agricultural Food Network

Gundula Proksch, University of Washington

Abstract

Chicago’s history and urban development have been connected to its role as a food hub and driver of technological innovations in the food industry. In the 1970s, the city started redefining its relation to agriculture by integrating various forms of urban agriculture. Today, the city is known for its strong network of community gardens, educational farms, and job training programs. Over the last decade, the city has also attracted various entrepreneurial, innovative controlled environment production facilities, such as hydroponic greenhouses, rooftop greenhouses, and vertical indoor farms, that refined their growing methods and economic models. Other urban farms deploy hybrid models that combine a robust social agenda with emerging, economically driven food production systems. These multi-layer urban agriculture operations with strong community and commercial objectives contribute to community empowerment and urban revitalization. This comparative analysis concludes a three-part mixed-method investigation of Chicago’s foodshed and urban agriculture networks, which move in scale from the Metropolitan region, City of Chicago, and organizational networks to this smallest scale of specific physical locations and architectural spaces. The investigation relies on publicly available data and datasets. It analyzes urban agricultural networks through (1) GIS-based mapping; (2) a review of organizational structures; and (3) an analysis of critical building projects, with a focus on the award-winning Farm on Ogden in the North Lawndale neighborhood and The Plant in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. This analysis of pioneering projects may inspire other community-minded cities and projects to establish innovative pathways. The identified novel approaches will help legislators, community leaders, planners, and architects to provide for growing urban populations, create common spaces, develop frameworks to support regionally sustainable food production, promote social equity, and improve the well-being of historically marginalized communities.

11:00am-12:30pm

Research Session

1.5 LU Credit

Urbanism: Envisioning Urbanism for Communities

Moderator: Yong Huang, Bowling Green State University (BGSU)

The Ordinary within the Extraordinary: The Ideology and Architectural Form of Boley, an “All-Black Town” in the Prairie

Jared Macken, Oklahoma State University

Abstract

In 1908, Booker T. Washington stepped off the Fort Smith and Western Railway train into the town of Boley, Oklahoma. Washington found a bustling main street home to over 2,500 African American citizens. He described this collective of individuals as unified around a common goal, “with the definite intention of getting a home and building up a community where they can, as they say, be ‘free.’”[1] The main street was the physical manifestation of this idea, the center of the community. It was comprised of ordinary banks, store front shops, theaters, and social clubs, all of which connected to form a dynamic cosmopolitan street—an architectural collective form.[2] Each building aligned with its neighbor creating a single linear street, a space where the culture of the town thrived. This public space became a symbol of the extraordinary lives and ideology of its citizens, who produced an intentional utopia in the middle of the prairie. Founded in 1903, Boley is one of more than fifty “All-Black Towns” that developed in “Indian Territory” before Oklahoma became a state. Despite their prominence, these towns’ potential and influence was suppressed when the territory became a state in 1907. State development was driven by lawmaker’s ambition to control the sovereign land of Native Americans and impose control over towns like Boley by enacting Jim Crow Laws legalizing segregation. This agenda manifests itself in the form and ideology of the state’s colonial towns. However, the story of the state’s history does not reflect the narrative of colonization. Instead, it is dominated by tales of sturdy “pioneers” realizing their role within the myth of manifest destiny. In contrast, Boley’s history is an alternative to this myth, a symbol of a radical ideology of freedom, and a form that reinforces this idea. Boley’s narrative begins to debunk the myth of manifest destiny and contrast with other colonial town forms. This paper explores the relationship between the architectural form of Boley’s main street and the town’s cultural significance, linking the founding community’s ideology to architectural spaces that transformed the ordinary street into a dynamic social space.[3] The paper also compares Boley with other main street towns from Oklahoma that were founded at the same time, showing how the architectural form of the street was used to reinforce different ideologies represented by different towns. The paper then compares Boley’s unified linear main street, which emphasized its citizens and their freedom, with two other town typologies: Perry’s centralized courthouse square that emphasized the seat of power that was colonizing Cherokee Nation land; and Douthat’s monument to mining, whose main street emphasized the town’s mining company, orienting its largest mineral elevator at the end of the street. Analysis of these slightly varied architectural forms and ideologies reorients the historical narrative of the state. As a result, these suppressed urban stories, in particular that of Boley’s, are able to make new contributions to architectural discourse on the city and also change the dominant narratives of American Expansion.

De-center / Expand Access: Decentralized Public Transit in Low Density Areas

Marleen Davis, University of Tennessee-Knoxville

Abstract