Winners of the 2017 Housing Competition

The American Institute of Architects, Custom Residential Architects Network (AIA CRAN) and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), have selected the recipients of the 2017 HERE+NOW: A House for the 21st Century Residential Student Design Competition. The competition recognizes seven exceptional studio projects that seamlessly integrate innovative, regenerative strategies within their broader design concepts. The program challenged students to submit projects that provide architecture students, with a platform to explore residential architecture and residential architectural practice.

The 2017 jury for the Housing Competition includes:

Aaron Bowman

Liollio Architecture

(Charleston, South Carolina)

Patricia Seitz

Massachusetts College of Art and Design

(Boston, Massachusetts)

Emily Roush-Elliott

Delta Design Build Workshop

(Greenwood, Mississippi)

Listed below are the names of the recipients, their school, the faculty sponsor, and project title.

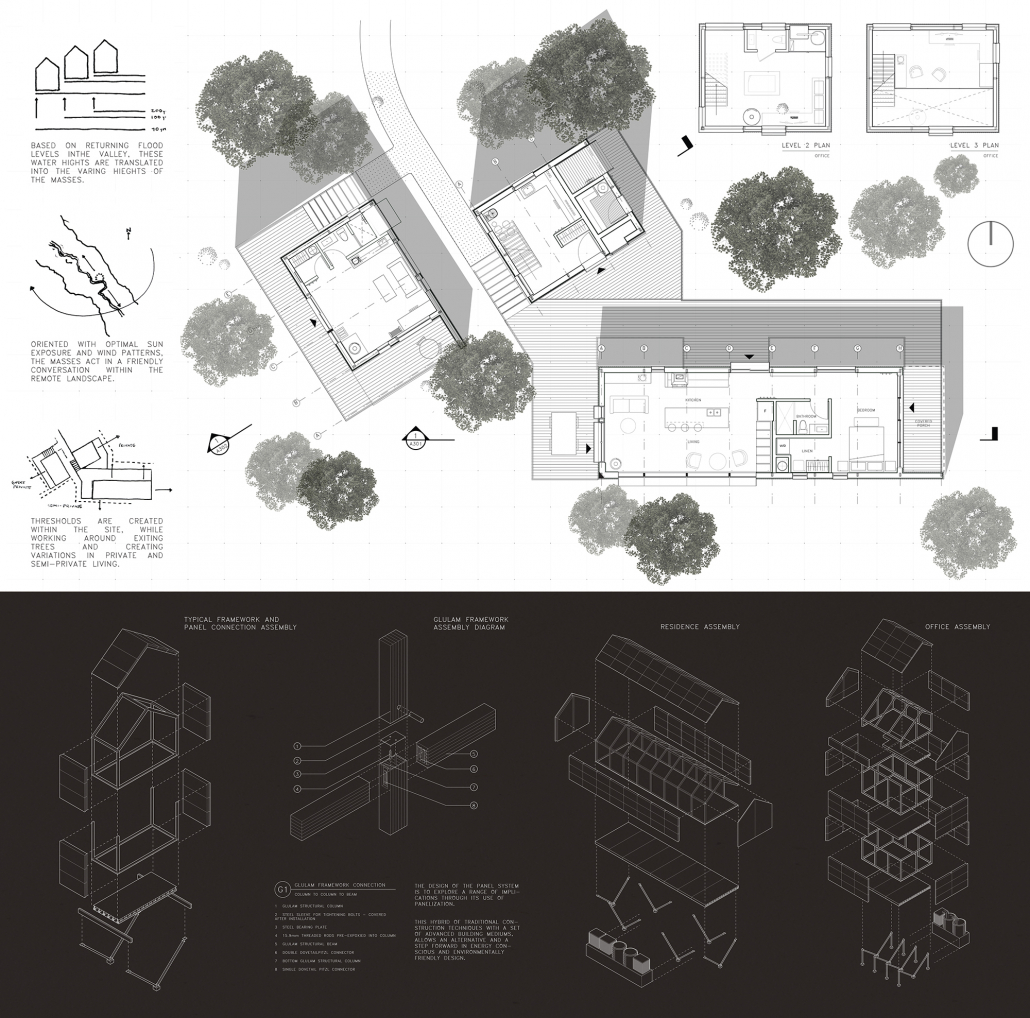

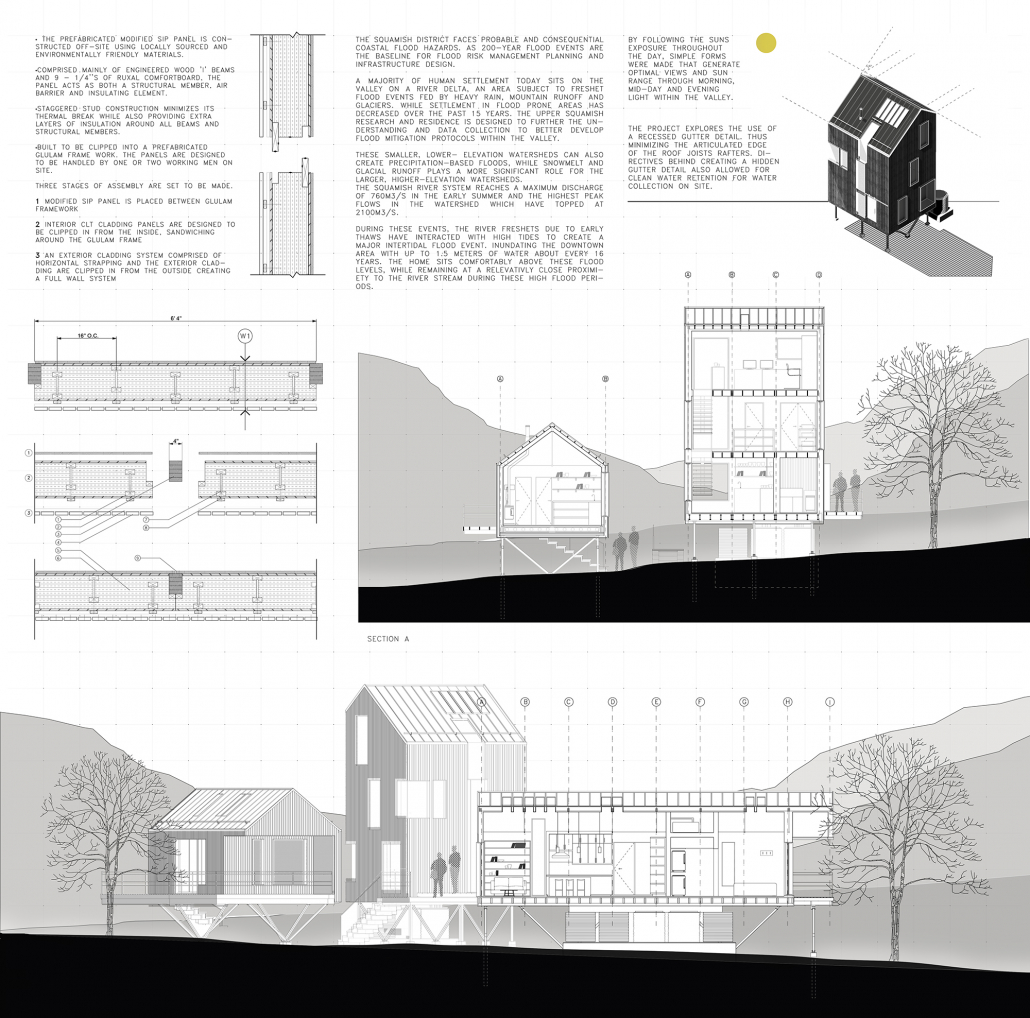

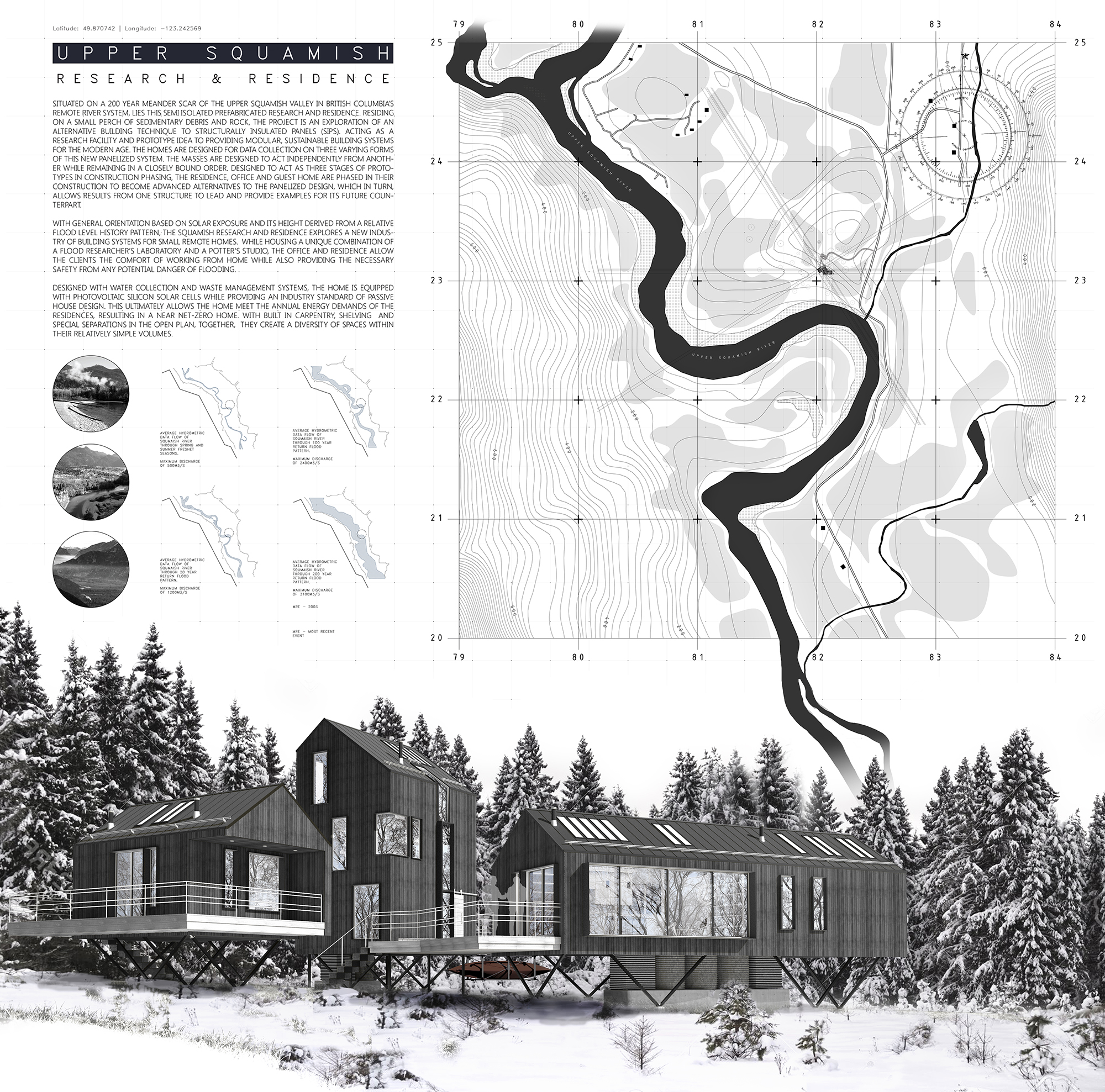

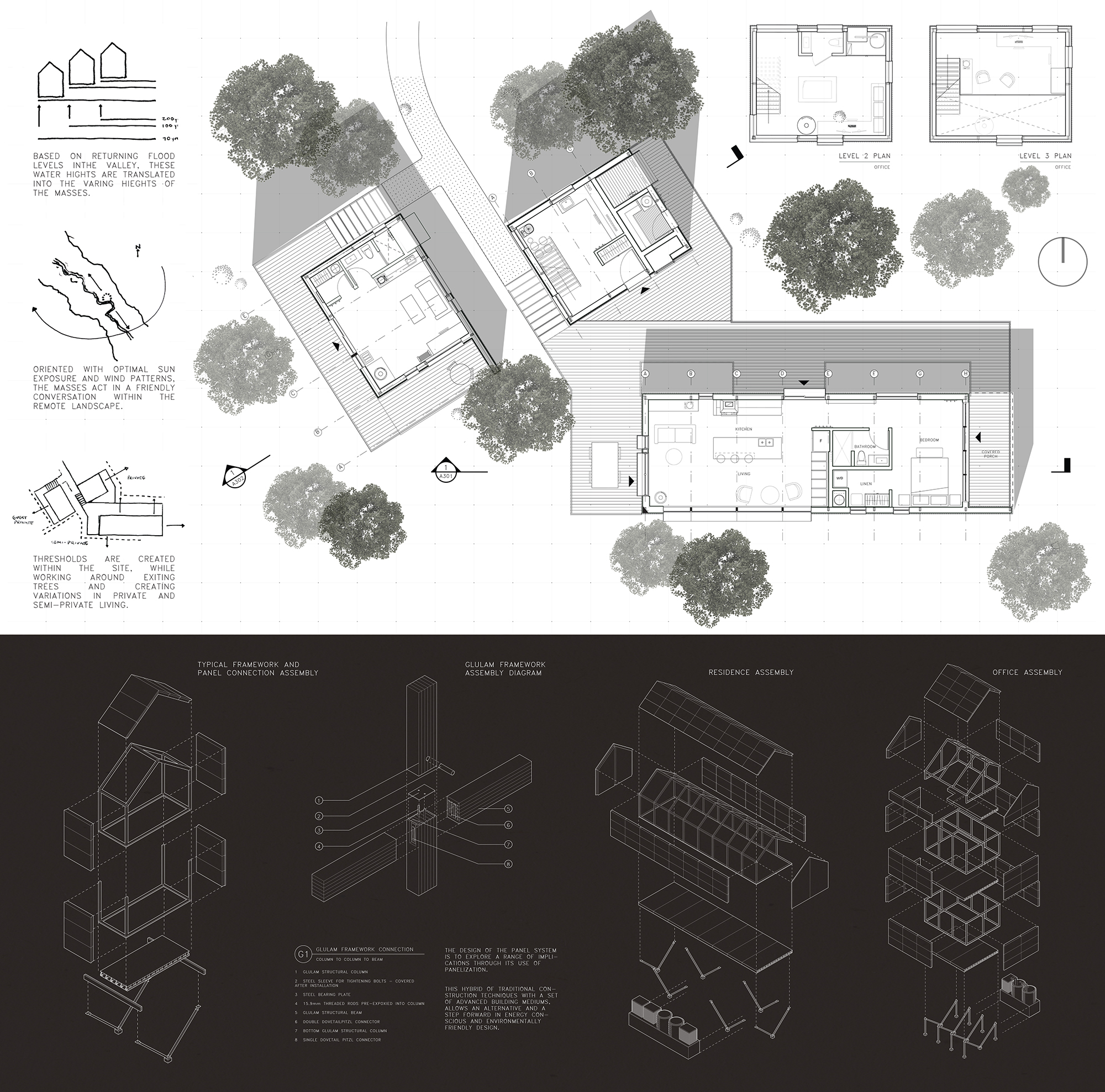

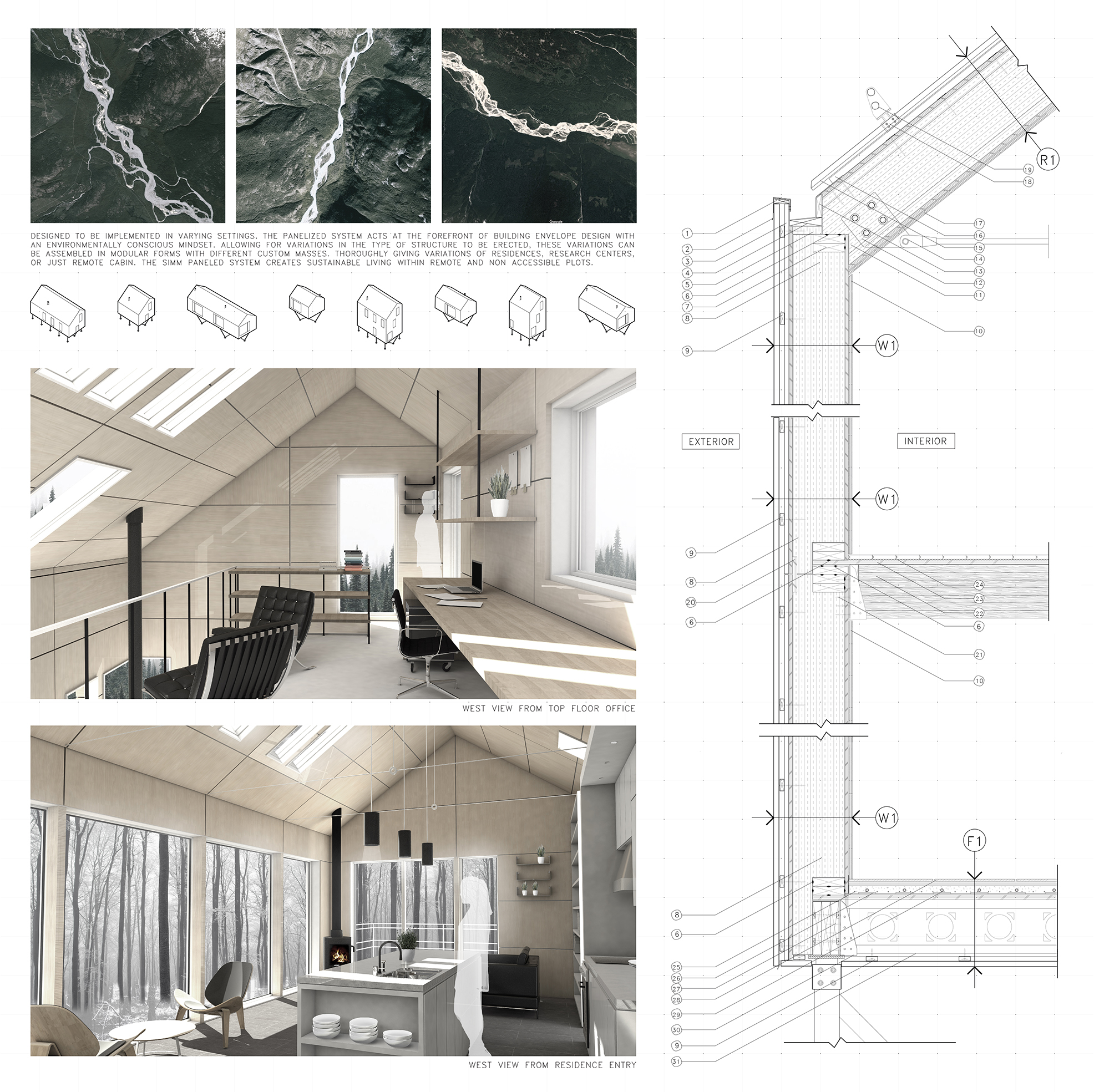

1st Place: UPPER SQUAMISH RESEARCH AND RESIDENCE

Student: Jesse Bird

Faculty Sponsor: Sheryl Boyle

Institution: Carleton University

Juror Comments

This winning project rose to the top for its excellent and in-depth attention to prefabrication, modular construction and building detail that approaches net-zero construction. The design addresses sustainability issues, climate, and flooding head on, and is sensitive, even poetic to issues of daylight. A multiple building layout makes it possible to limit how much space is heated, which is well suited to the cold climate on the Pacific west coast of Canada. The building sections are thoughtfully composed and the development of the design and clear graphics, including multiple versions of wall panels, are compelling and thorough.

Project Description

The Dogtrot Duo home was designed for the Independence Heights community in Houston, Texas. Established in 1908 as a completely self-sustaining community, Independence Heights was incorporated in 1915, becoming the first African American municipality in Texas. Once a thriving, predominantly African American community, there is now a nearly equal percentage of Hispanic and Black residents, and nearly a quarter of the community’s population is living below the poverty level. Despite these challenges, Independence Heights is on the brink of redevelopment due to its close proximity to downtown Houston. Descendants of the original settlers welcome the revitalization, but are also anxious about losing their heritage.

The 4th year undergraduate design studios focus on regenerative design and sustainable strategies in a public interest design and service learning format. We engage residents and community leaders, using their input to inform our design strategies. In addition to the challenge of gentrification, there is a substantial population of senior citizens who wish to age in place, while the next generation has migrated to the suburbs seeking better housing, services and opportunities. This trend, combined with devastation from Tropical Storm Allison and Hurricane Ike, has left the neighborhood largely vacant.

Our design reflects careful attention to these issues. Taken in conjunction with our mission of regenerative, affordable design, the Dogtrot Duo is a practical infill solution to support revitalization efforts that helps elders to stay in the community and young families to move back. The duplex doubles the density of a single lot and accommodates a number of living scenarios. The 1,200 square foot two bedroom unit will support young families in the 80% AMI range, while the 900 square foot one bedroom unit might support elders, singles, or young couples in the 50% AMI range. The dogtrot increases marketability by creating a duplex that looks and feels like the traditional single family homes in the neighborhood.

Design decisions included developing the site to create inviting outdoor spaces that encourage fellowship among residents and neighbors. Care was taken to elevate the vernacular typology of the carport to function as a comfortable gathering space for people. Generous porches cultivate community while providing eyes on the street. Bungalow styling further maintains the aesthetic quality of the neighborhood. The dogtrot configuration borrows from a Texas vernacular solution that provides a comfortable outdoor living space while assisting with natural ventilation through the living spaces of both units.

While the exterior is intentionally contextual, the interiors respond to modern day living with open floor plans. Each home features built-in solutions for workspaces, storage, and seating to maximize space and efficiency. High ceilings help the home to feel larger, and operable windows and clerestories provide ample daylight and natural ventilation to increase comfort.

Finally, the Dogtrot Duo is designed to be an affordable, net zero energy solution. Designed to meet rigorous Passive House certification and building science standards, the home achieves a HERS score of zero with the option to install a 5kW PV system to achieve net zero energy.

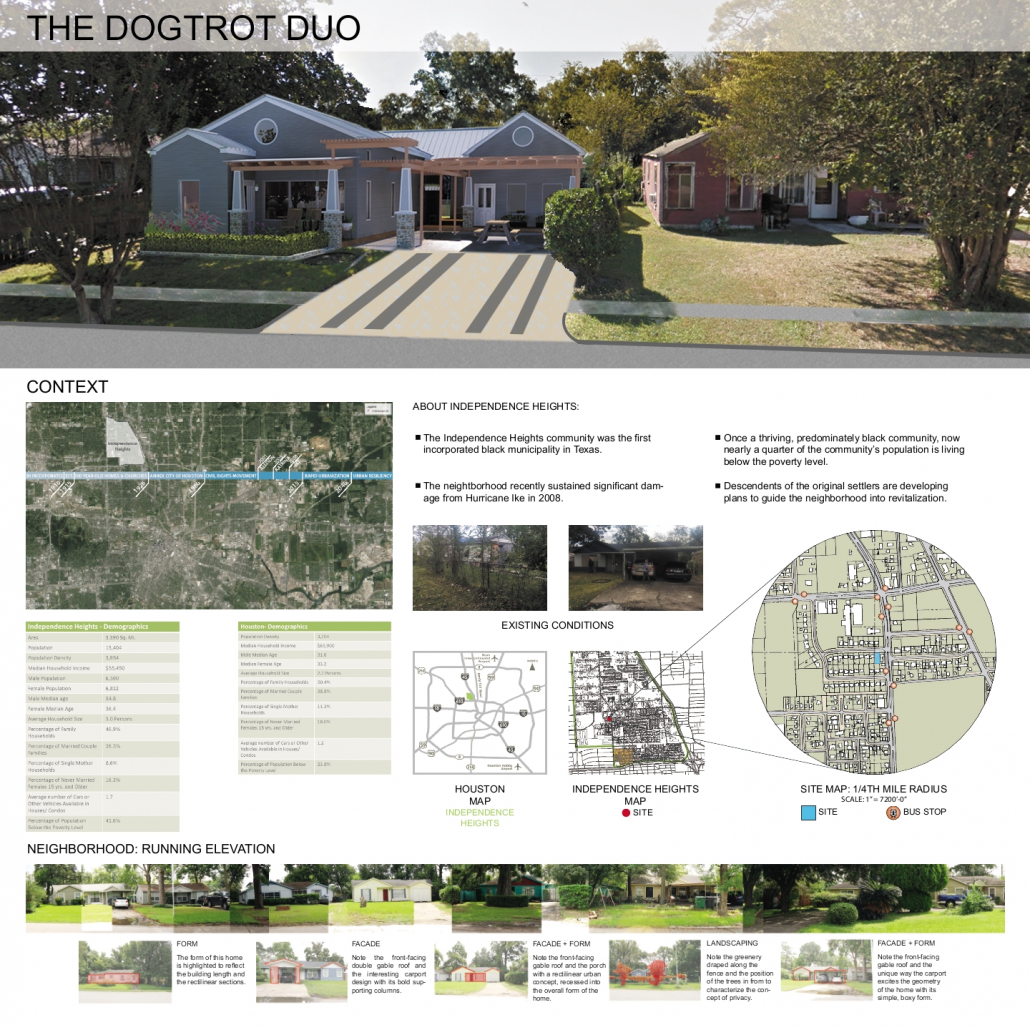

2nd Place: THE DOGTROT DUO

Students: Shannen Martin, Sean Benson, Jabbar Cobbs, Kimberly Montgomery, & Emanuel Soito, Prairie View A&M University

Faculty Sponsor: Shelly Pottorf, Prairie View A&M University

Juror Comments

This project stood out for its research and responses to all five criteria for judging, which grounded it in reality and made it more tangible. The design is responsive to the social and economic issues of the Independence Heights neighborhood in Houston, Texas, and sensitive to the local climate. The jury is particularly impressed with the rigorous analysis of affordability issues and participatory design process that included community stakeholders, which the studio used in developing designs. The students engaged with the suburban context and showed a well-informed understanding of the neighborhood and contemporary housing challenges while considering client needs.

Project Description

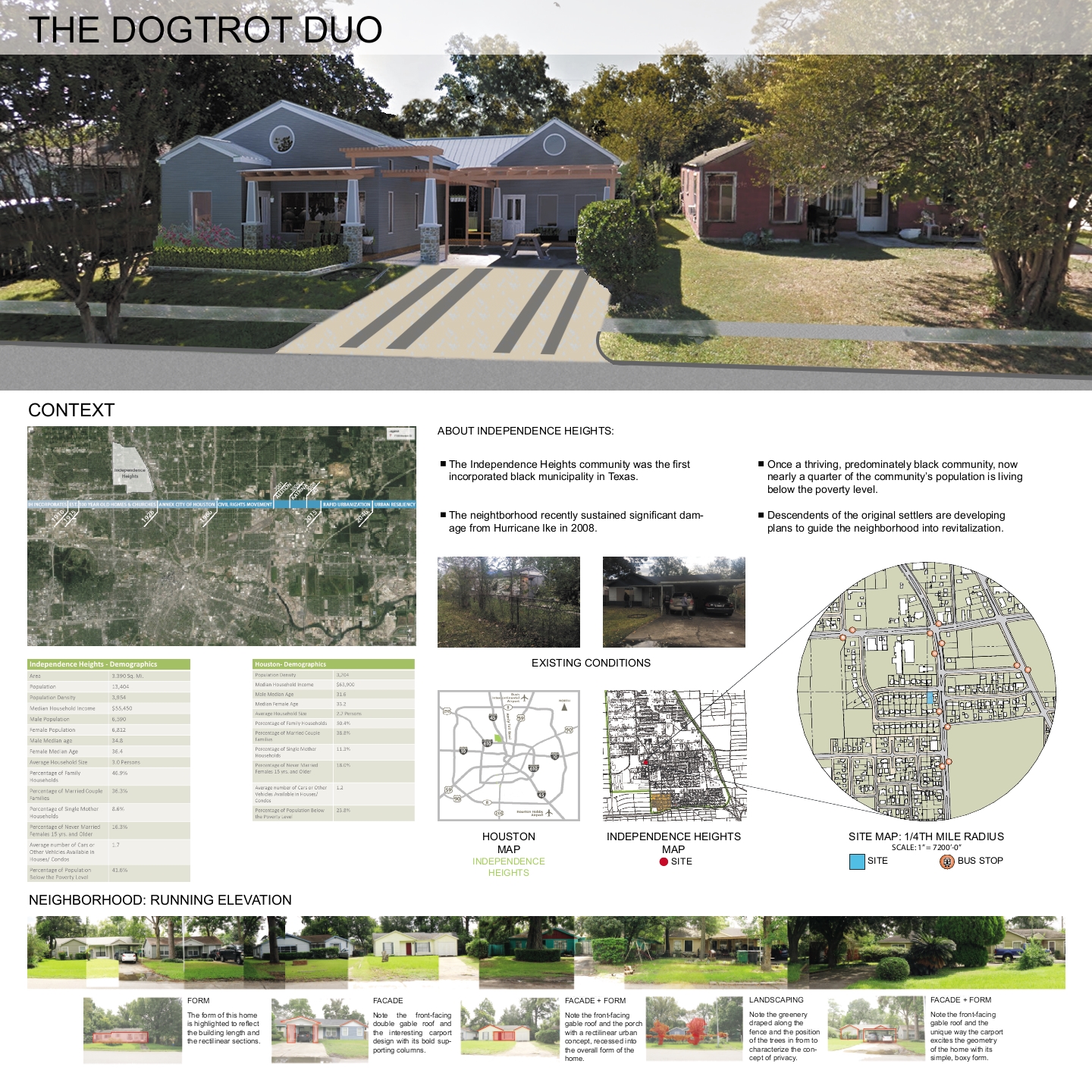

The Dogtrot Duo home was designed for the Independence Heights community in Houston, Texas. Established in 1908 as a completely self-sustaining community, Independence Heights was incorporated in 1915, becoming the first African American municipality in Texas. Once a thriving, predominantly African American community, there is now a nearly equal percentage of Hispanic and Black residents, and nearly a quarter of the community’s population is living below the poverty level. Despite these challenges, Independence Heights is on the brink of redevelopment due to its close proximity to downtown Houston. Descendants of the original settlers welcome the revitalization, but are also anxious about losing their heritage.

The 4th year undergraduate design studios focus on regenerative design and sustainable strategies in a public interest design and service learning format. We engage residents and community leaders, using their input to inform our design strategies. In addition to the challenge of gentrification, there is a substantial population of senior citizens who wish to age in place, while the next generation has migrated to the suburbs seeking better housing, services and opportunities. This trend, combined with devastation from Tropical Storm Allison and Hurricane Ike, has left the neighborhood largely vacant.

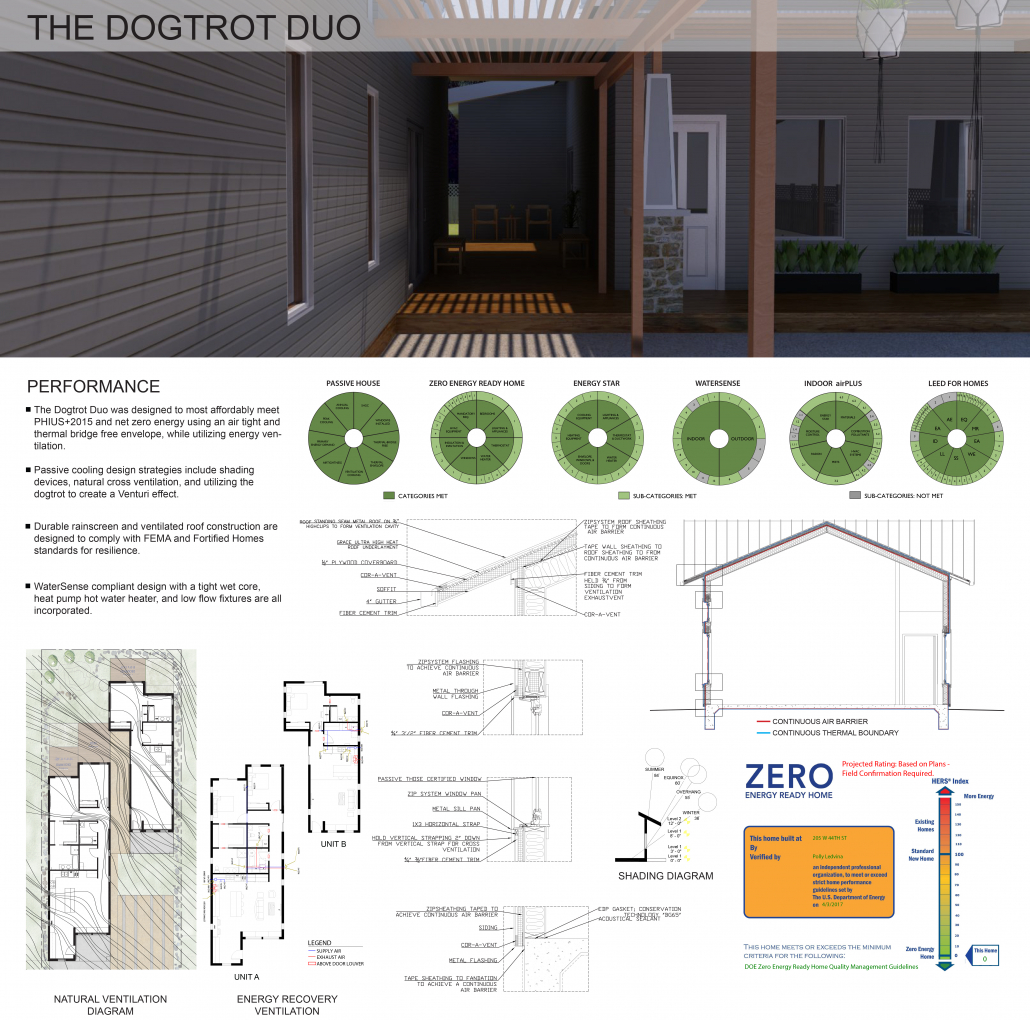

Our design reflects careful attention to these issues. Taken in conjunction with our mission of regenerative, affordable design, the Dogtrot Duo is a practical infill solution to support revitalization efforts that helps elders to stay in the community and young families to move back. The duplex doubles the density of a single lot and accommodates a number of living scenarios. The 1,200 square foot two bedroom unit will support young families in the 80% AMI range, while the 900 square foot one bedroom unit might support elders, singles, or young couples in the 50% AMI range. The dogtrot increases marketability by creating a duplex that looks and feels like the traditional single family homes in the neighborhood.

Design decisions included developing the site to create inviting outdoor spaces that encourage fellowship among residents and neighbors. Care was taken to elevate the vernacular typology of the carport to function as a comfortable gathering space for people. Generous porches cultivate community while providing eyes on the street. Bungalow styling further maintains the aesthetic quality of the neighborhood. The dogtrot configuration borrows from a Texas vernacular solution that provides a comfortable outdoor living space while assisting with natural ventilation through the living spaces of both units.

While the exterior is intentionally contextual, the interiors respond to modern day living with open floor plans. Each home features built-in solutions for workspaces, storage, and seating to maximize space and efficiency. High ceilings help the home to feel larger, and operable windows and clerestories provide ample daylight and natural ventilation to increase comfort.

Finally, the Dogtrot Duo is designed to be an affordable, net zero energy solution. Designed to meet rigorous Passive House certification and building science standards, the home achieves a HERS score of zero with the option to install a 5kW PV system to achieve net zero energy.

3rd Place: COMMON GROUND: COLLECTIVE LIVING IN SEATTLE, WA

Student: Ariel Scholten, University of Washington

Faculty Sponsors: Elizabeth Golden & Richard Mohler, University of Washington

Juror Comments

This concept is awarded for its broad applicability as an urban response in a detached single-family neighborhood of downtown Seattle, of a shared housing solution, and its potential use as a model in other locations. The proposal responded to local demographics current in the area including students, and singles in addition to families, and provided community space in the design sensitive to scale, public-private distinctions and public co-working spaces. The jury also appreciated the distinct graphic style and boards composition. The floor plan is strong and shows a thoughtful use of light coupled with transparency. The differentiation between public and private spaces is very clear, which allows the building to take on both public and private realms in an expansion of the definition of urban living space.

Project Description

Seattle is one of the fastest growing cities in the US with among the nation’s fastest rising housing costs. Yet, nearly two thirds of the city’s developable land area is zoned for detached single family dwellings at suburban densities. The Wallingford neighborhood of Seattle, located north of Downtown, is home to families, singles and students, many of whom are long-time Seattle residents. The neighborhood is known for early 20th century craftsman style houses, mixed-use residential zones, and a plethora of parks and schools. The neighborhood is currently dealing with issues of increasing density as well as proposals for upzoning portions of the neighborhood to accommodate multi-family structures, which some residents feel will compromise the scale and character of the neighborhood. At the same time, there has been a demographic shift to a more independent lifestyle, including “settling down” at an older age, among millennials. This has changed the priorities and living arrangements of singles, with more people living for longer periods of time with non-relatives. A parallel shift towards a live/work lifestyle that allows one to work from home while valuing community and social engagement is also taking place.

Common Ground responds to all of these conditions by providing shared living spaces for its residents and a space for collaboration and engagement for the neighborhood as a whole, while being sensitive to the existing neighborhood context. The proposal is zoned with the most ‘public’ spaces facing the street and the most private facing the alley. Viewed from the street, Common Ground is of a consistent scale with its neighbors and offers transparency and a welcoming entry to a community co-working space, providing a strong connection to the neighborhood and enhancing the web of community connections. Private suites on the alley provide each resident with a place of refuge and solitude, allowing them a sense of privacy while having direct access to the community. The provision of eight sleeping units also increases the residential density without altering the scale and character of the neighborhood. Between the community co-working space and the private bedrooms suites are the shared living spaces. A kitchen, living area, reading room, green house and several outdoor spaces provide an environment for the strengthening of social bonds and wellbeing within the household. They offer areas for enrichment, knowledge, nourishment, relaxation, conversation and connection to nature to provide a framework for a vibrant and supportive household. Connecting the more public and private spaces, the shared living spaces enliven the home and provide a sense of inclusion.

Common Ground is a 21st Century hybrid housing solution that responds to the global crisis of housing affordability, changing household demographics, living/working relationships and a desire to retain existing neighborhood character. It does so in a way that cultivates a strong sense of community for both the household within and the neighborhood outside.

Honorable Mention

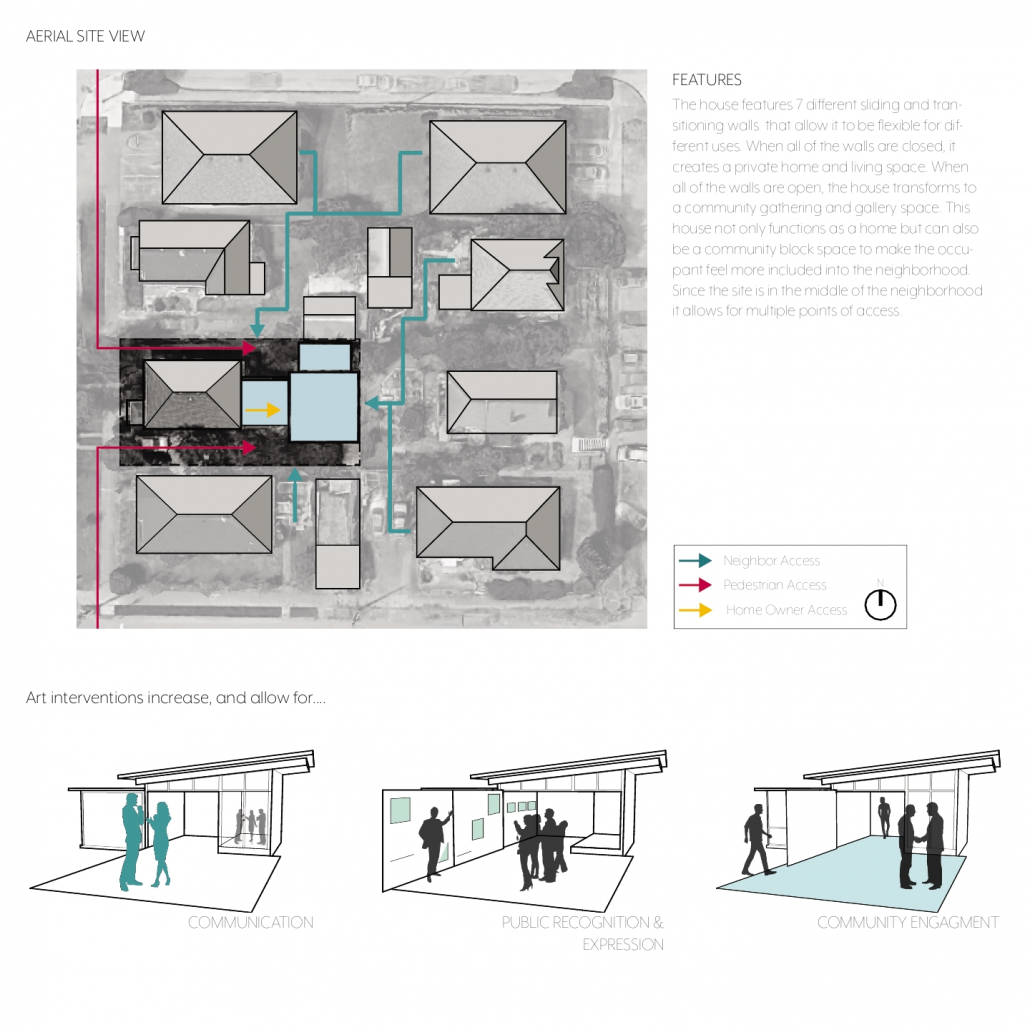

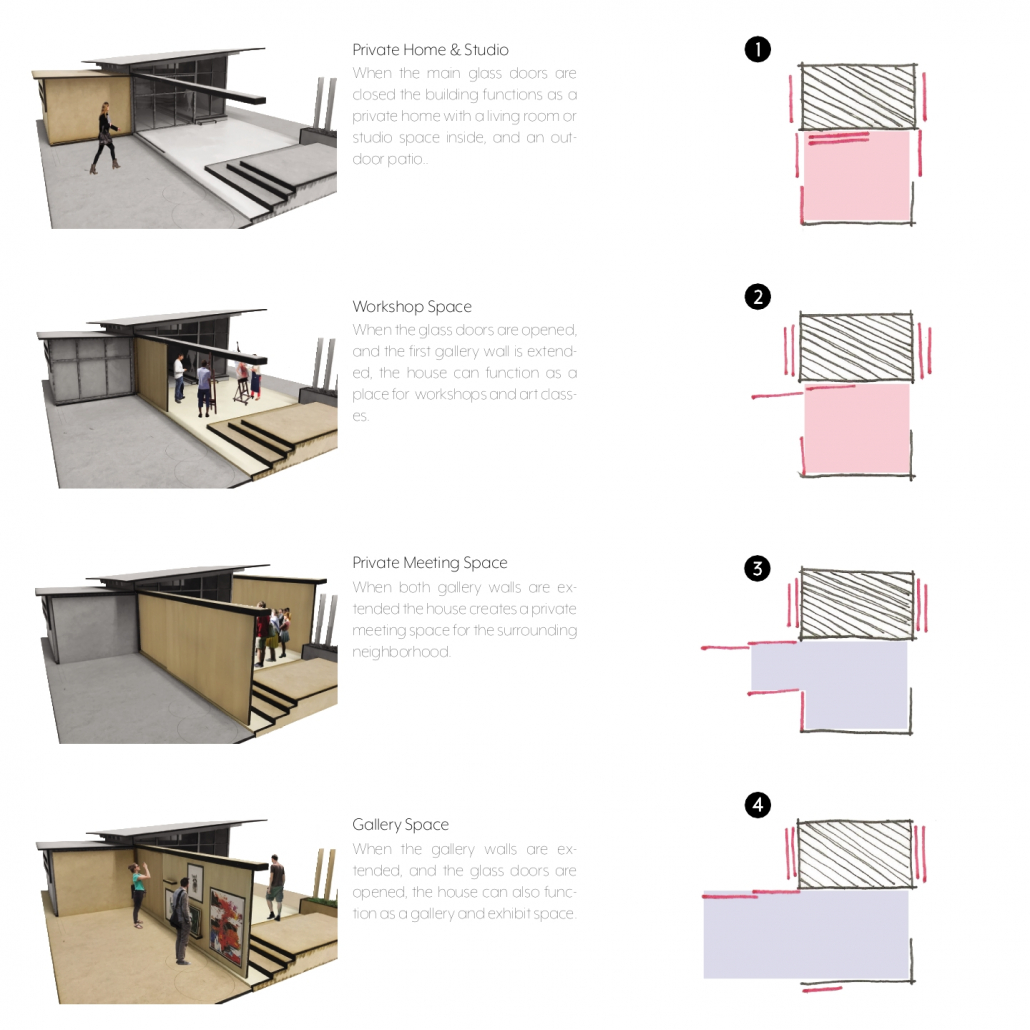

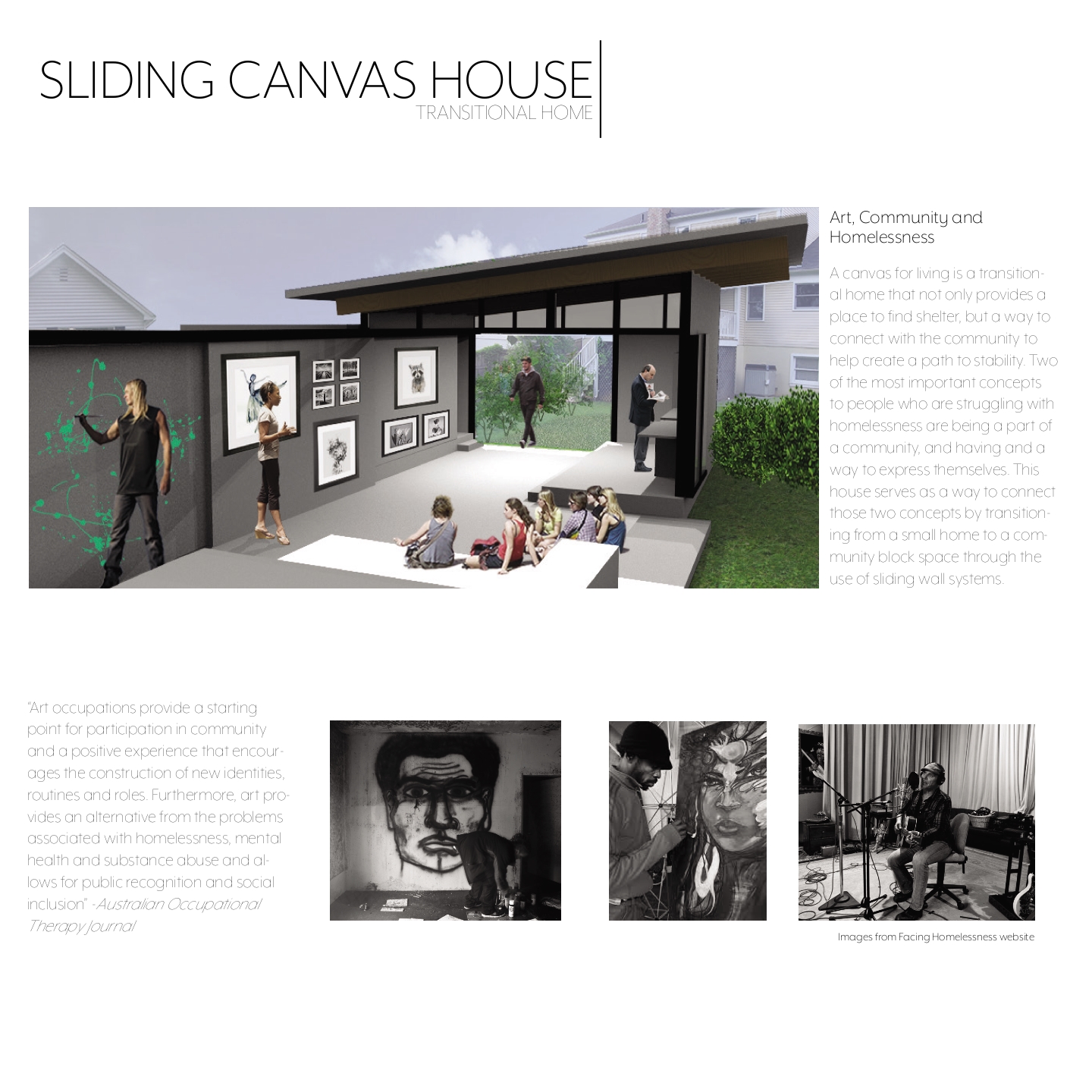

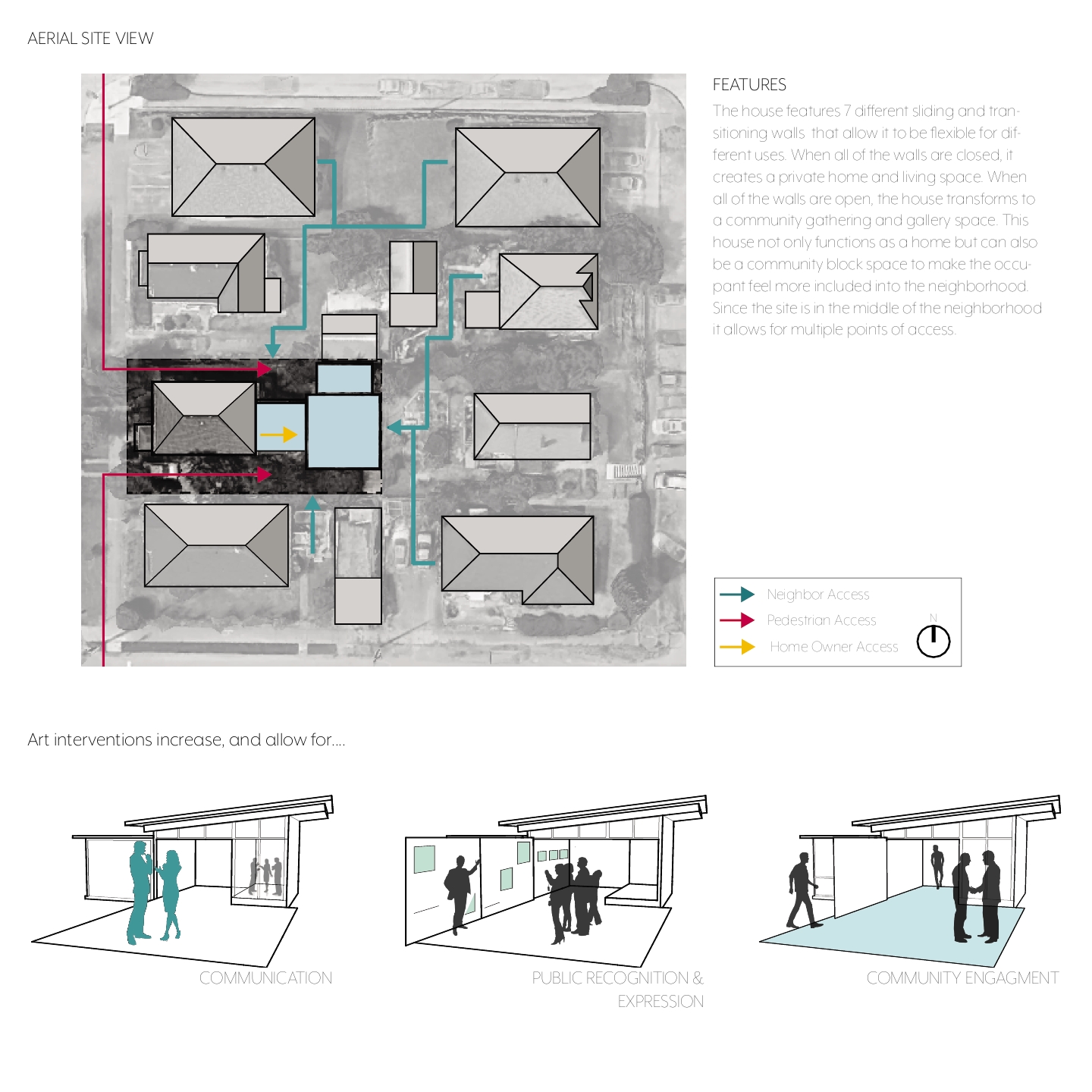

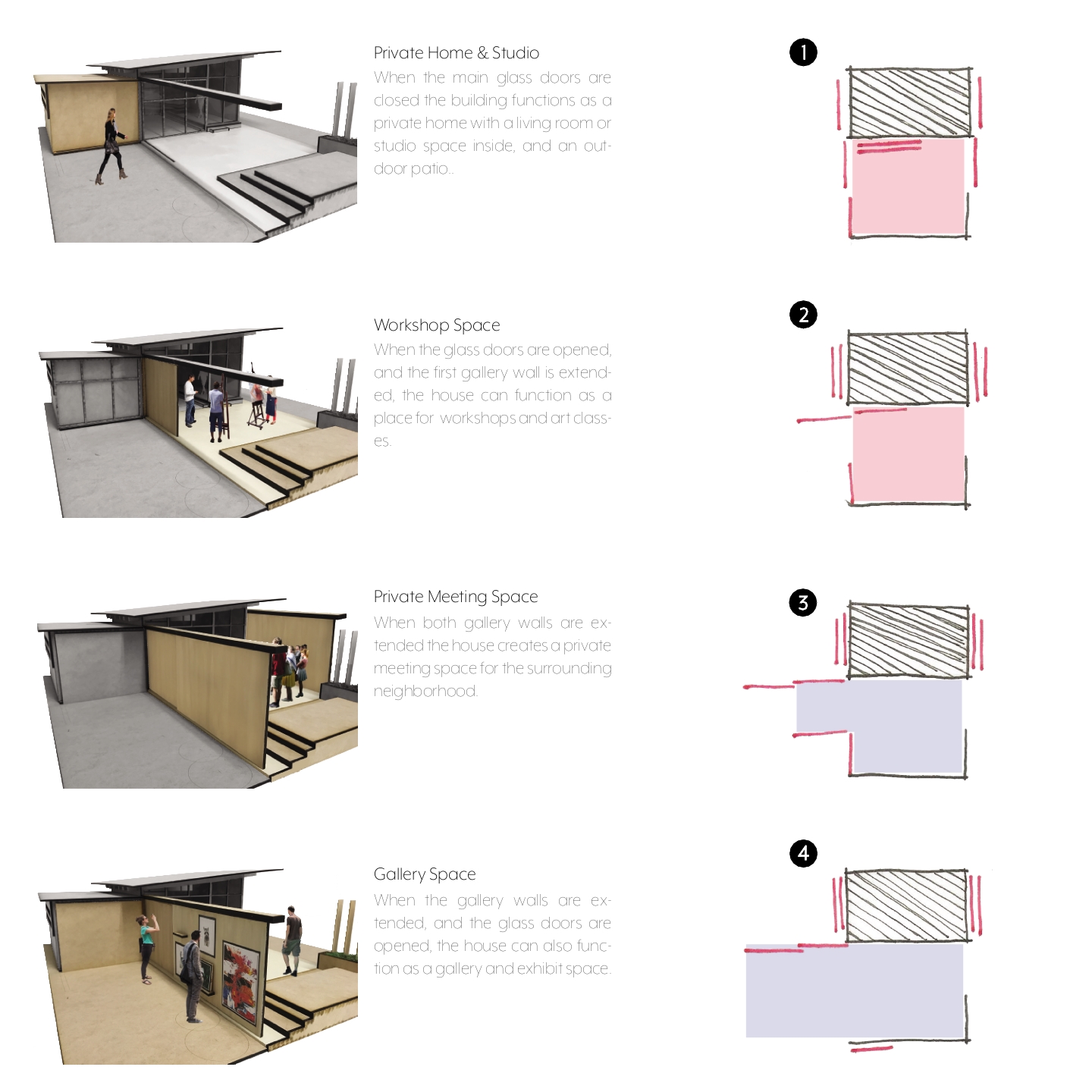

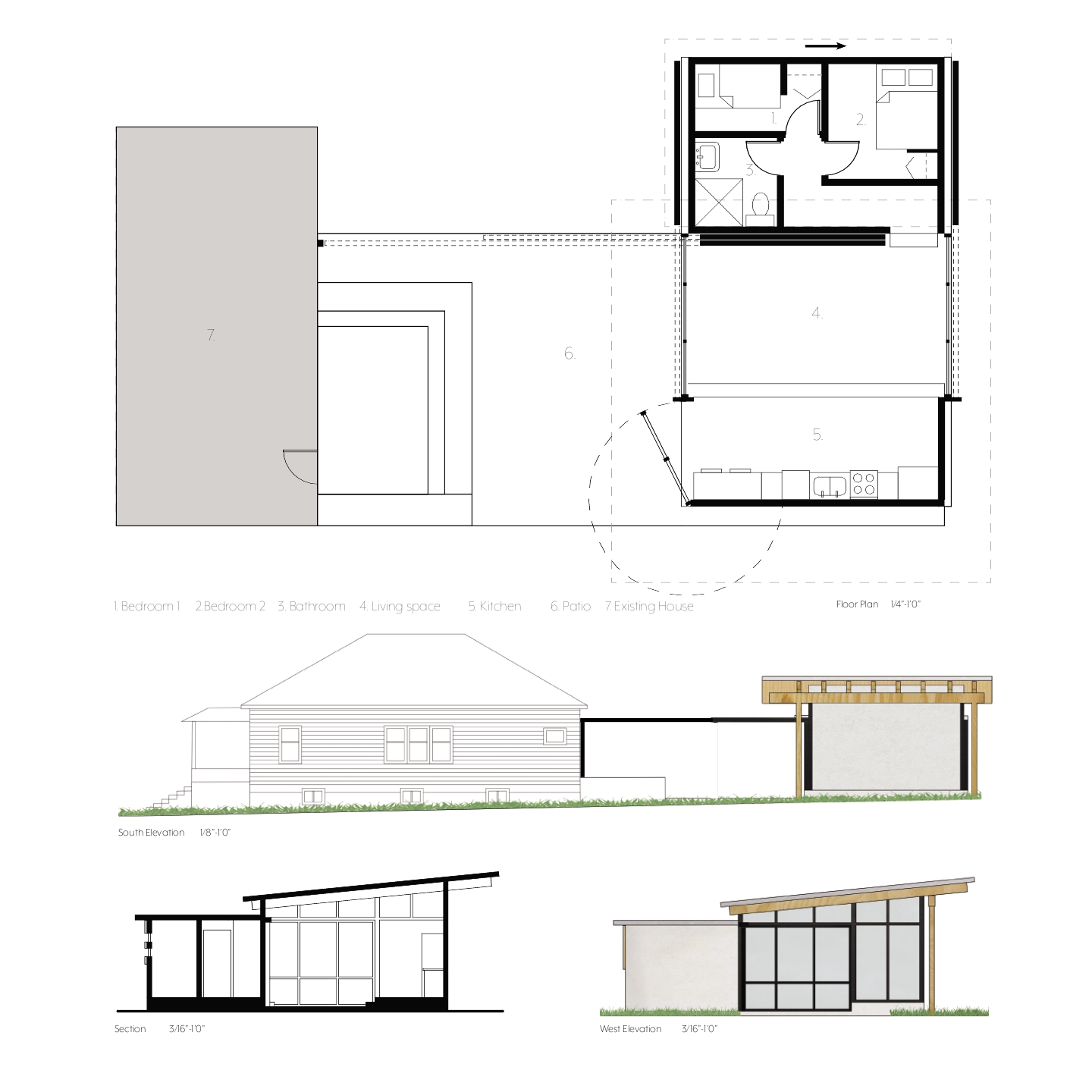

SLIDING CANVAS HOUSE: TRANSITIONAL HOME

Student: Samantha Geibel, Washington State University

Faculty Sponsor:Taiji Miyasaka, Washington State University

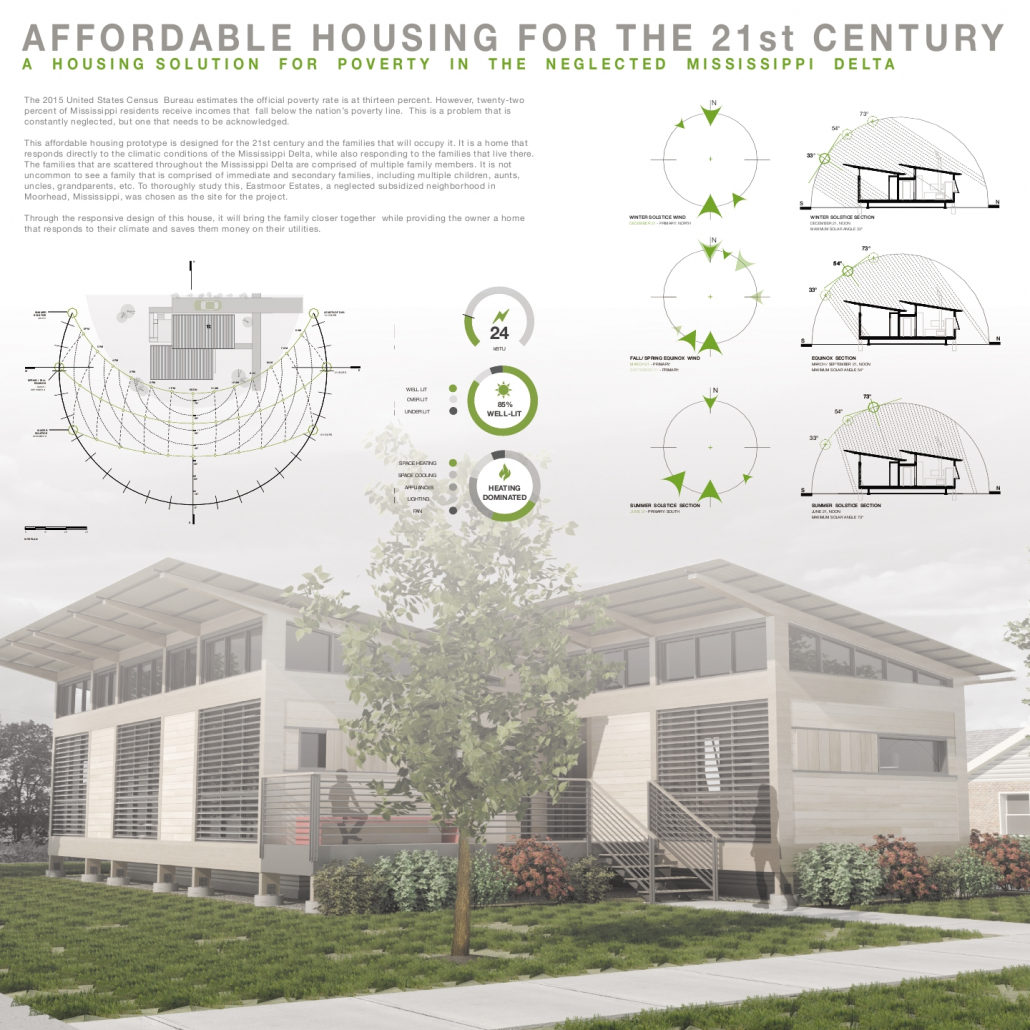

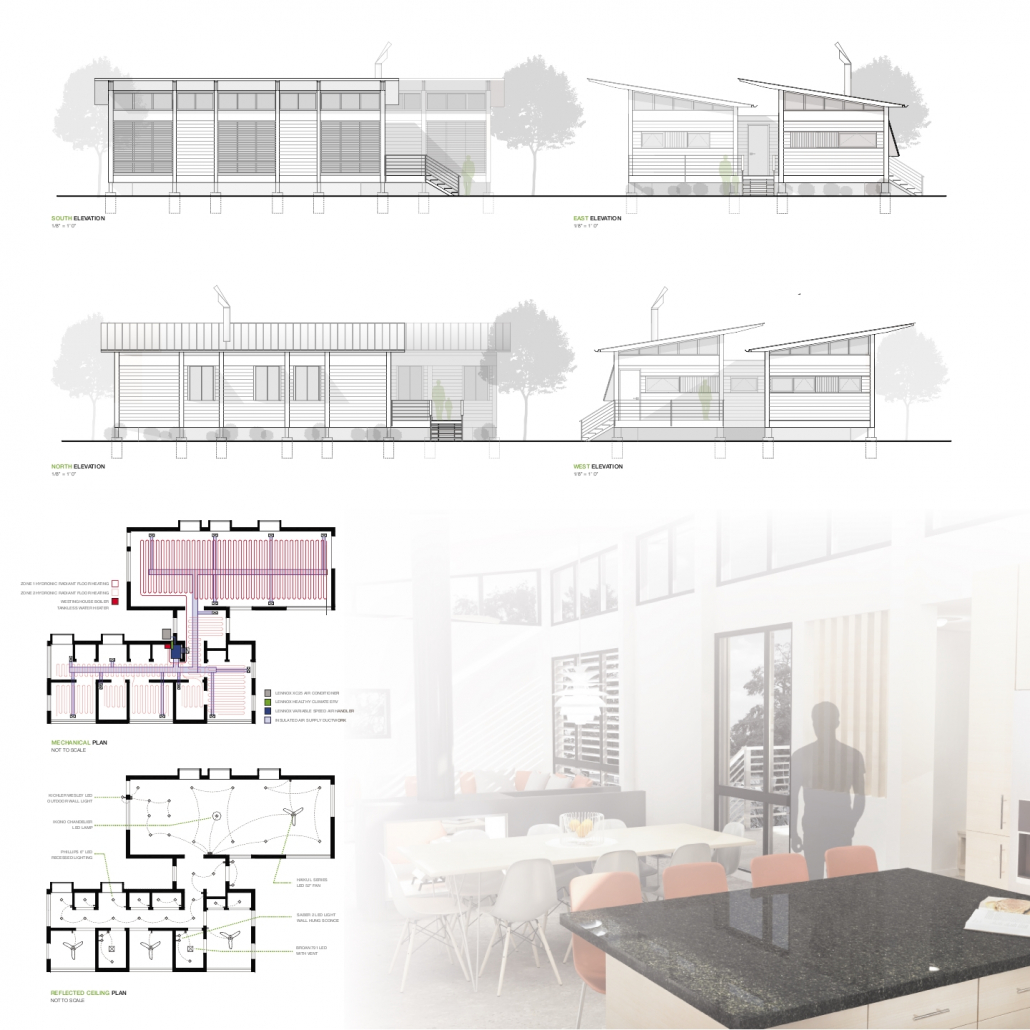

Honorable Mention

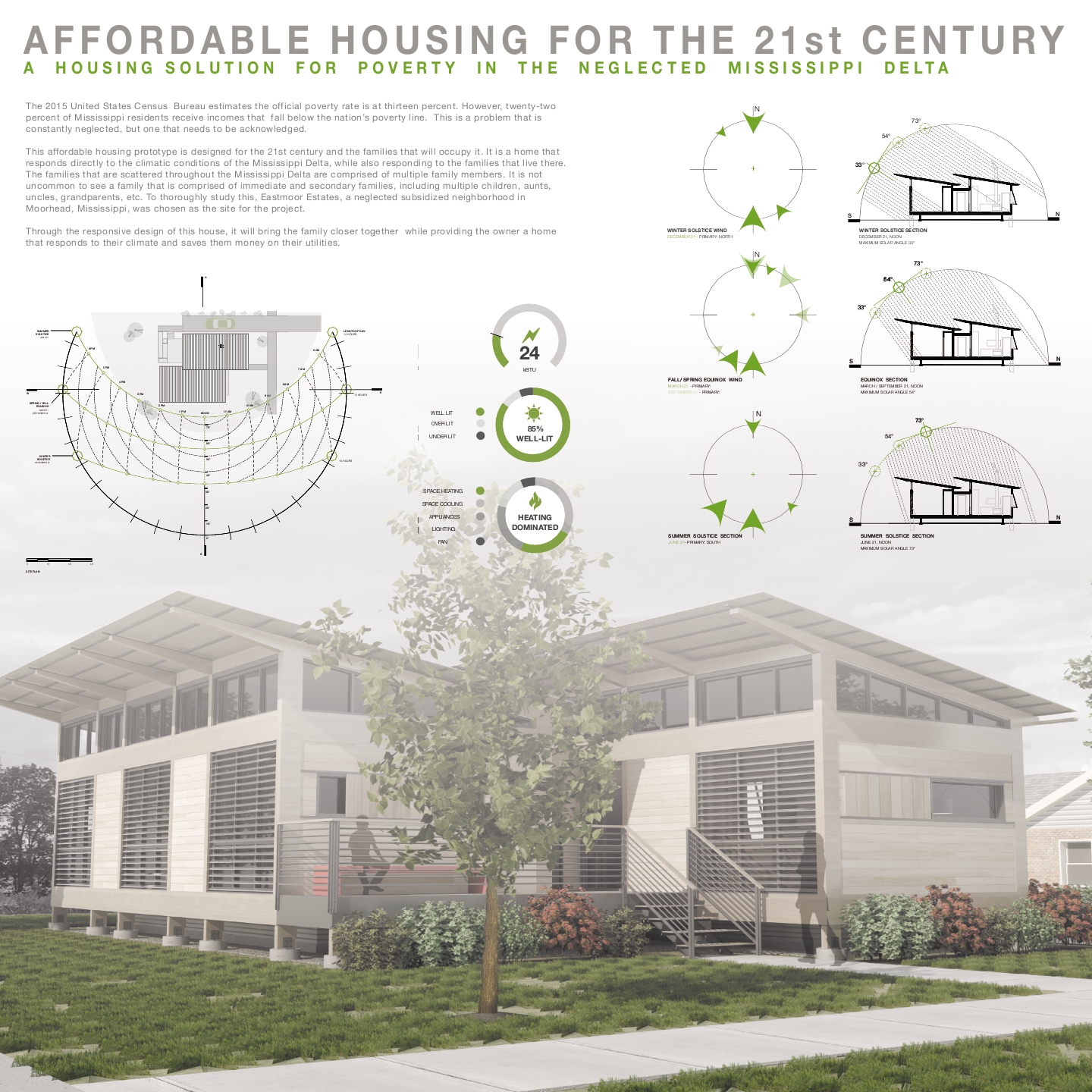

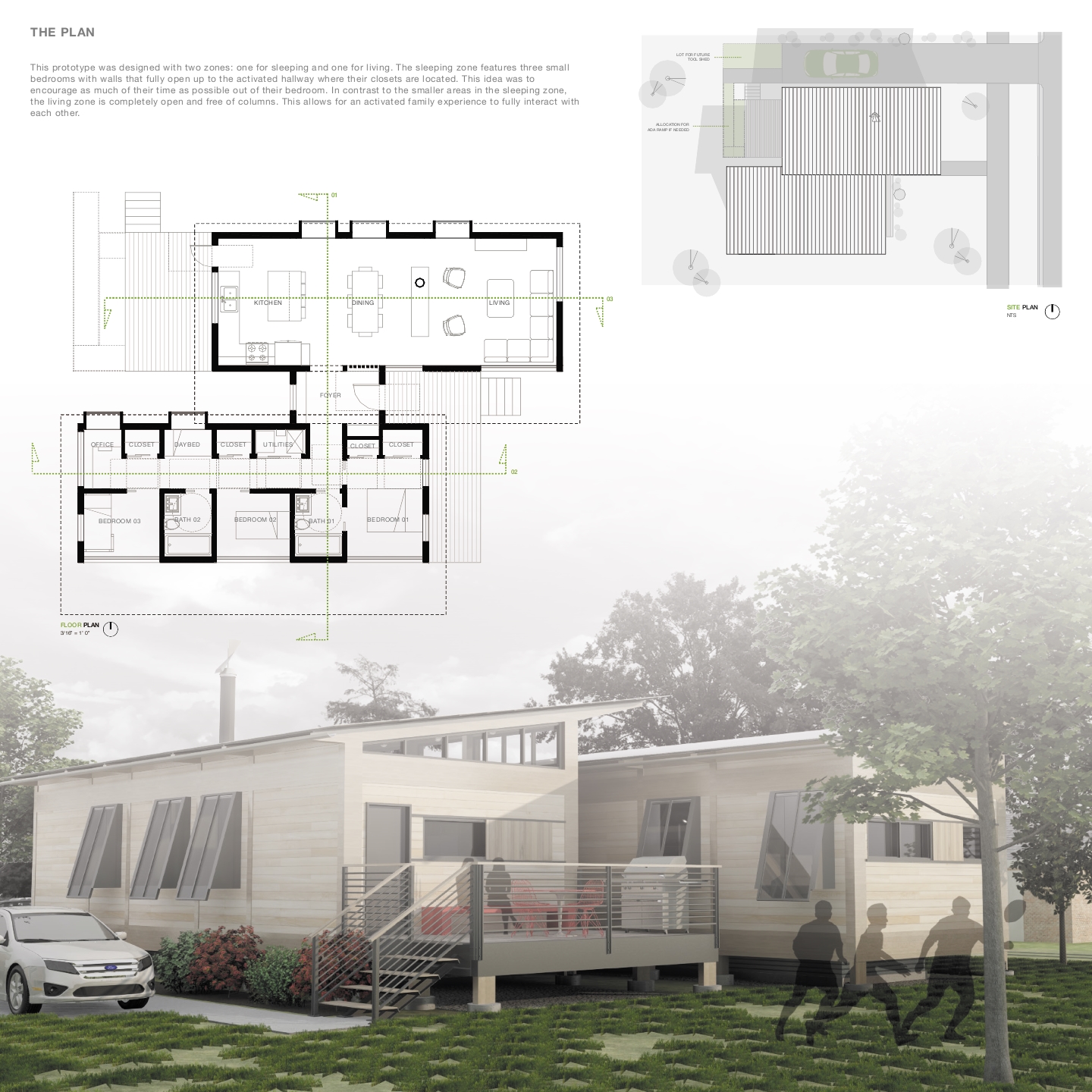

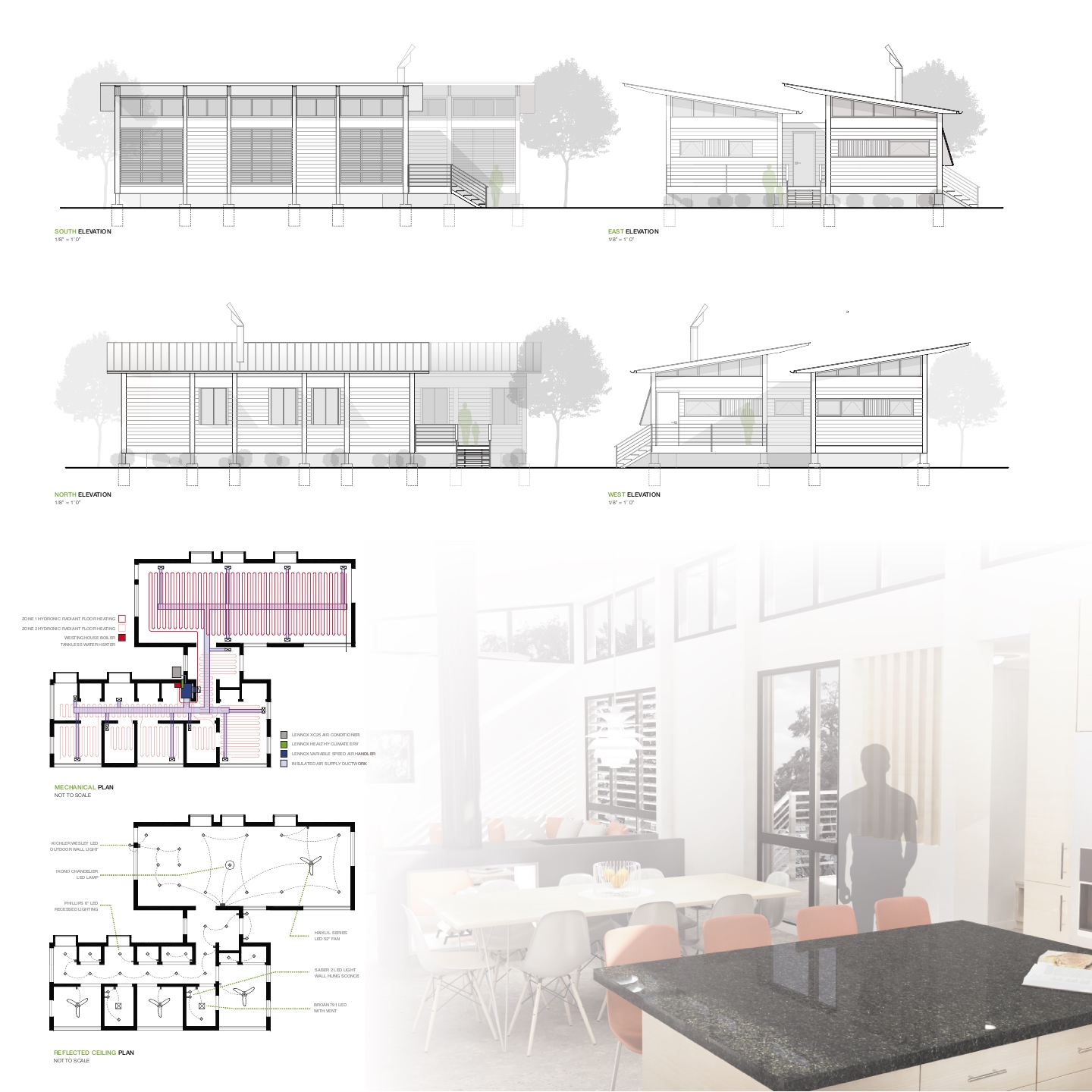

AFFORDABLE HOUSING FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

Student: Zachary Henry, Mississippi State University

Faculty Sponsor: Emily M. McGlohn, Mississippi State University

Honorable Mention

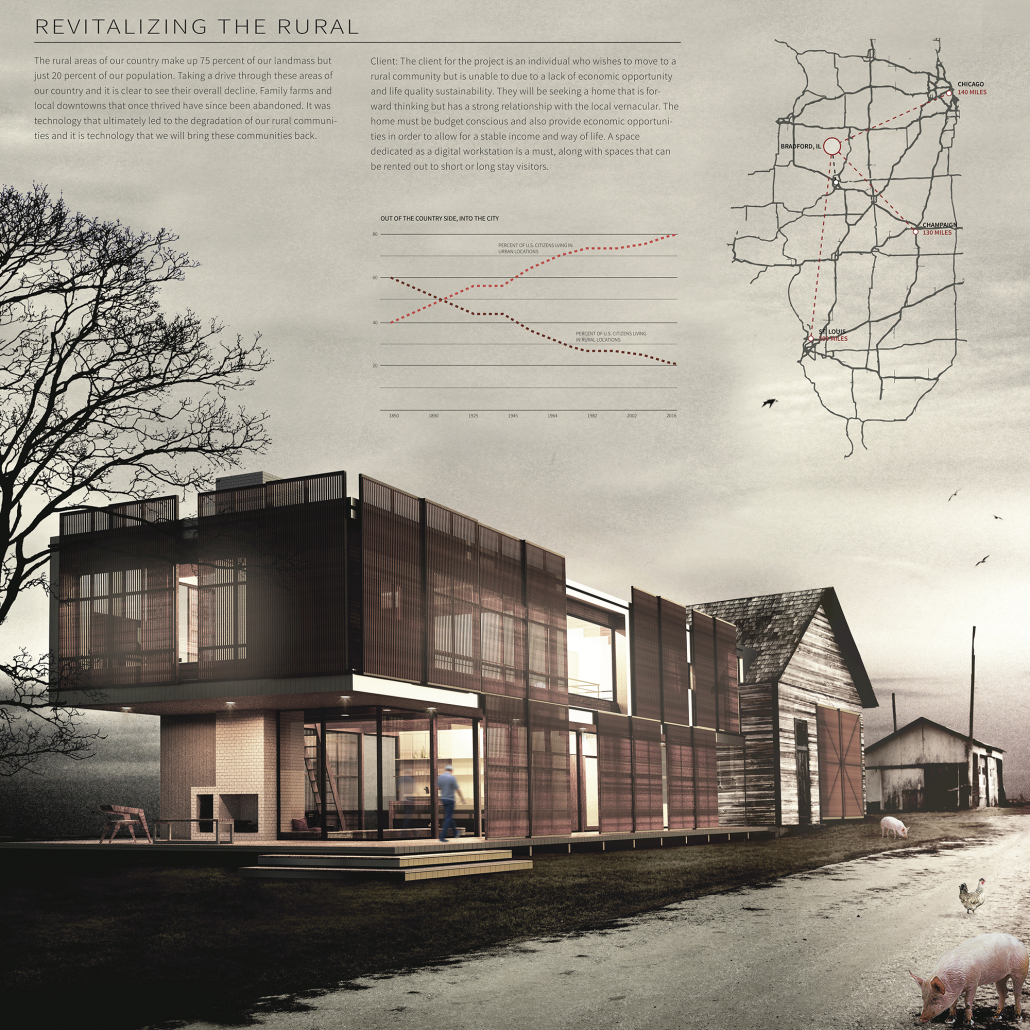

REVITALIZING THE RURAL

Student: Jacob Eble, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Faculty Sponsor: Mark Stephen Taylor, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Honorable Mention

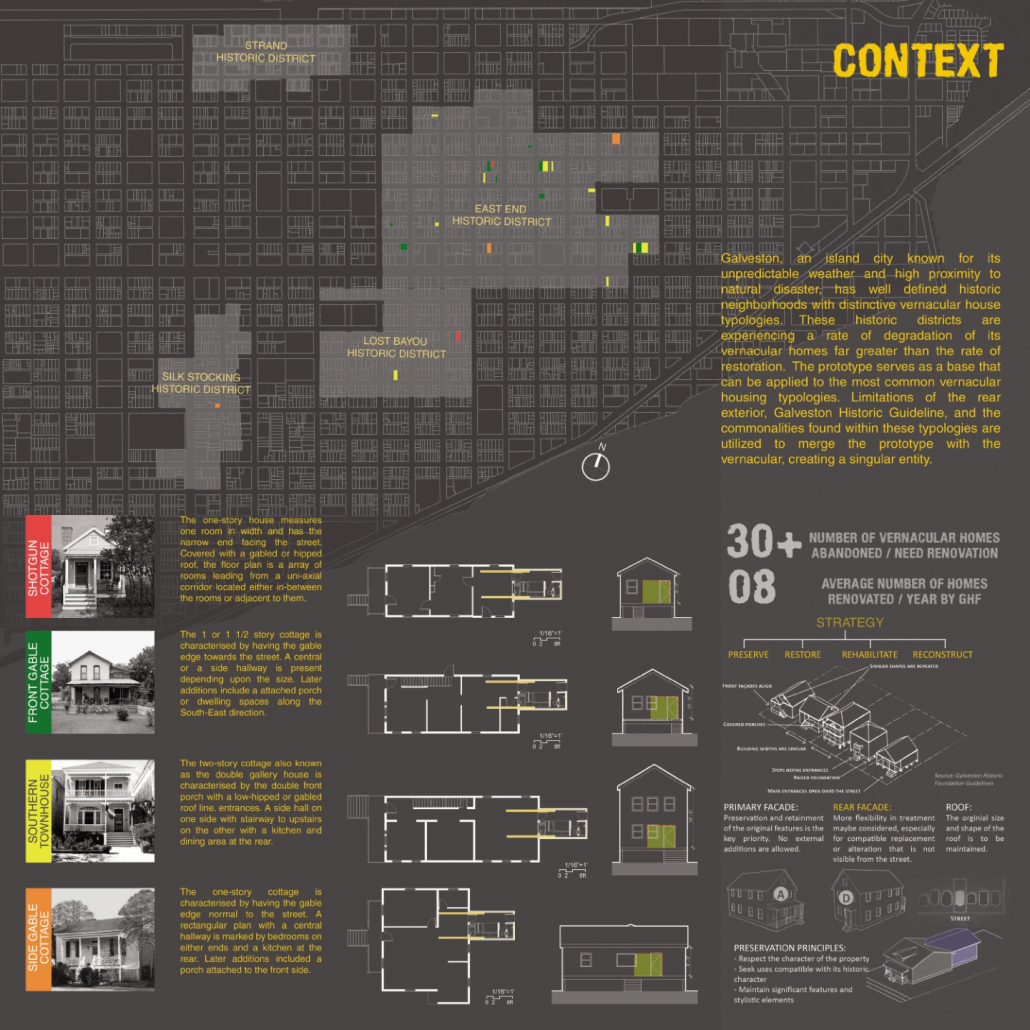

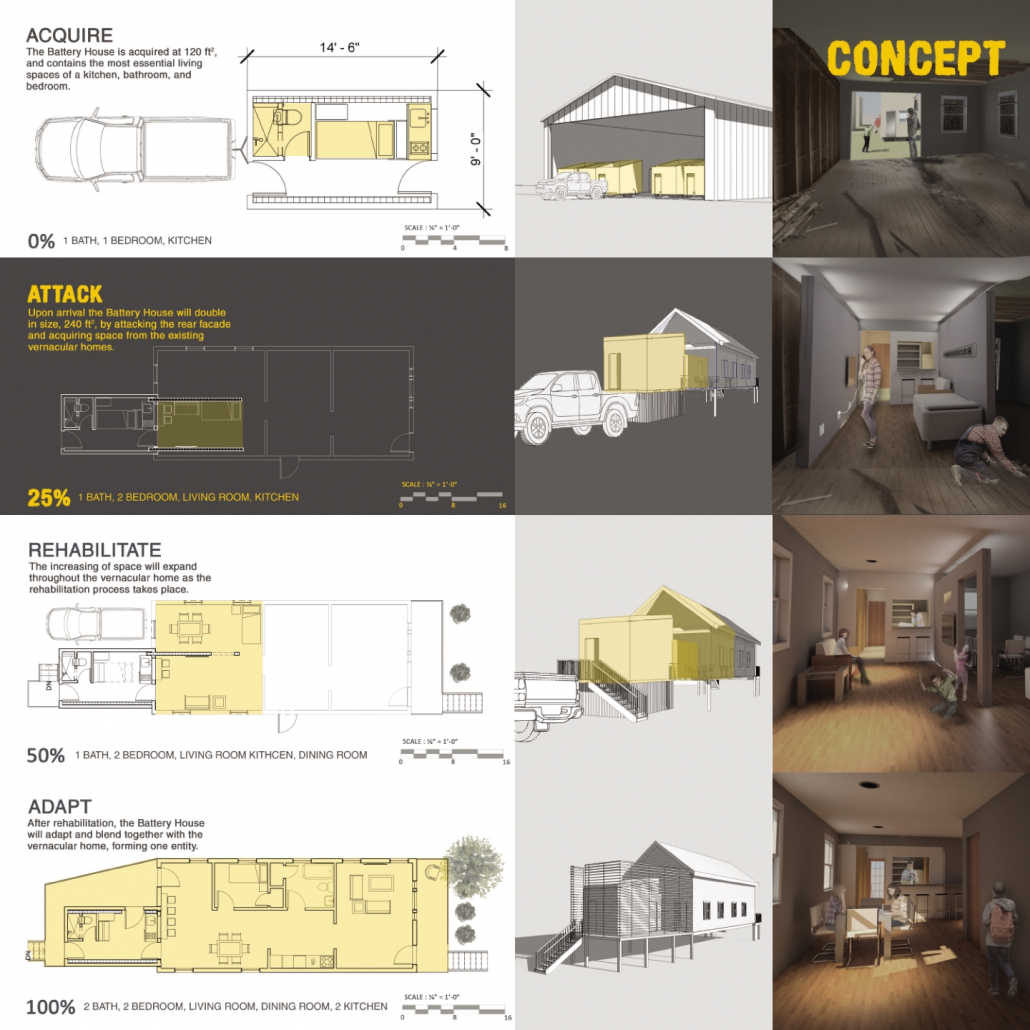

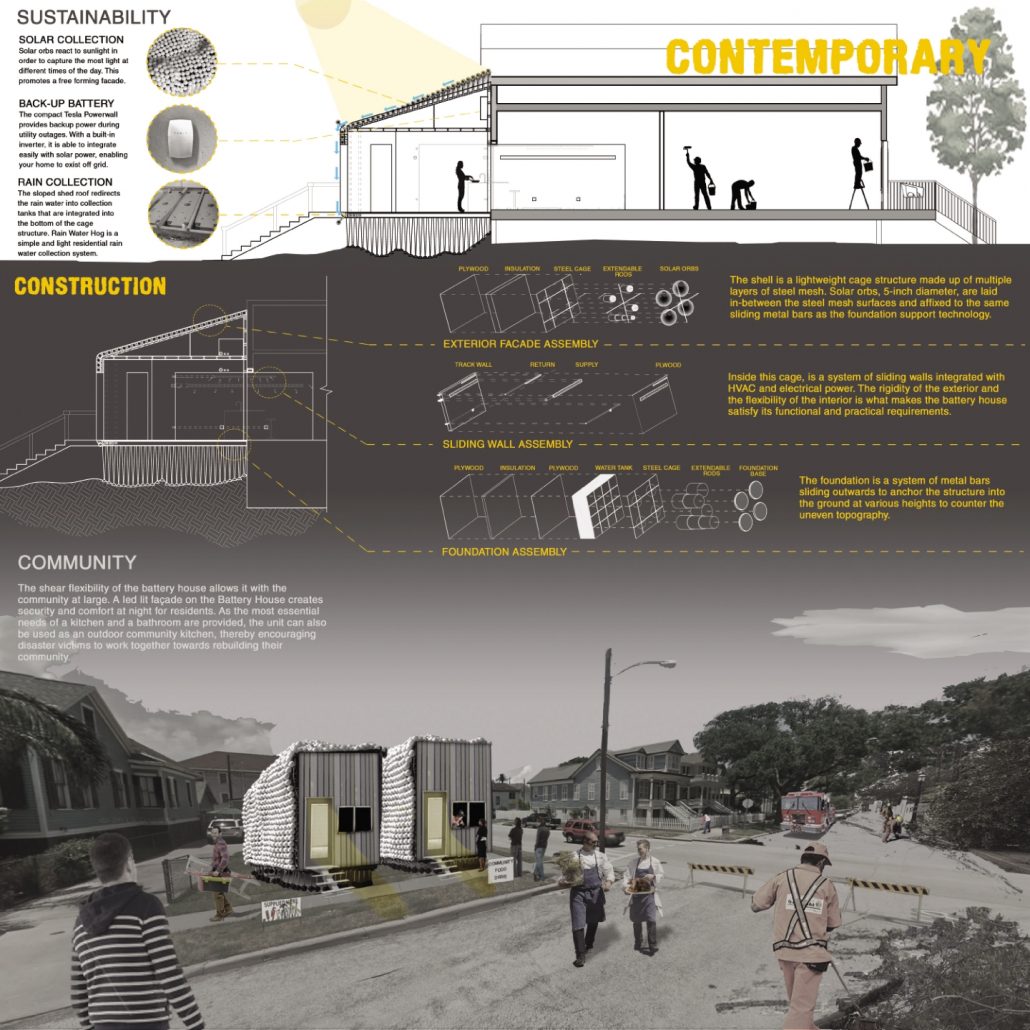

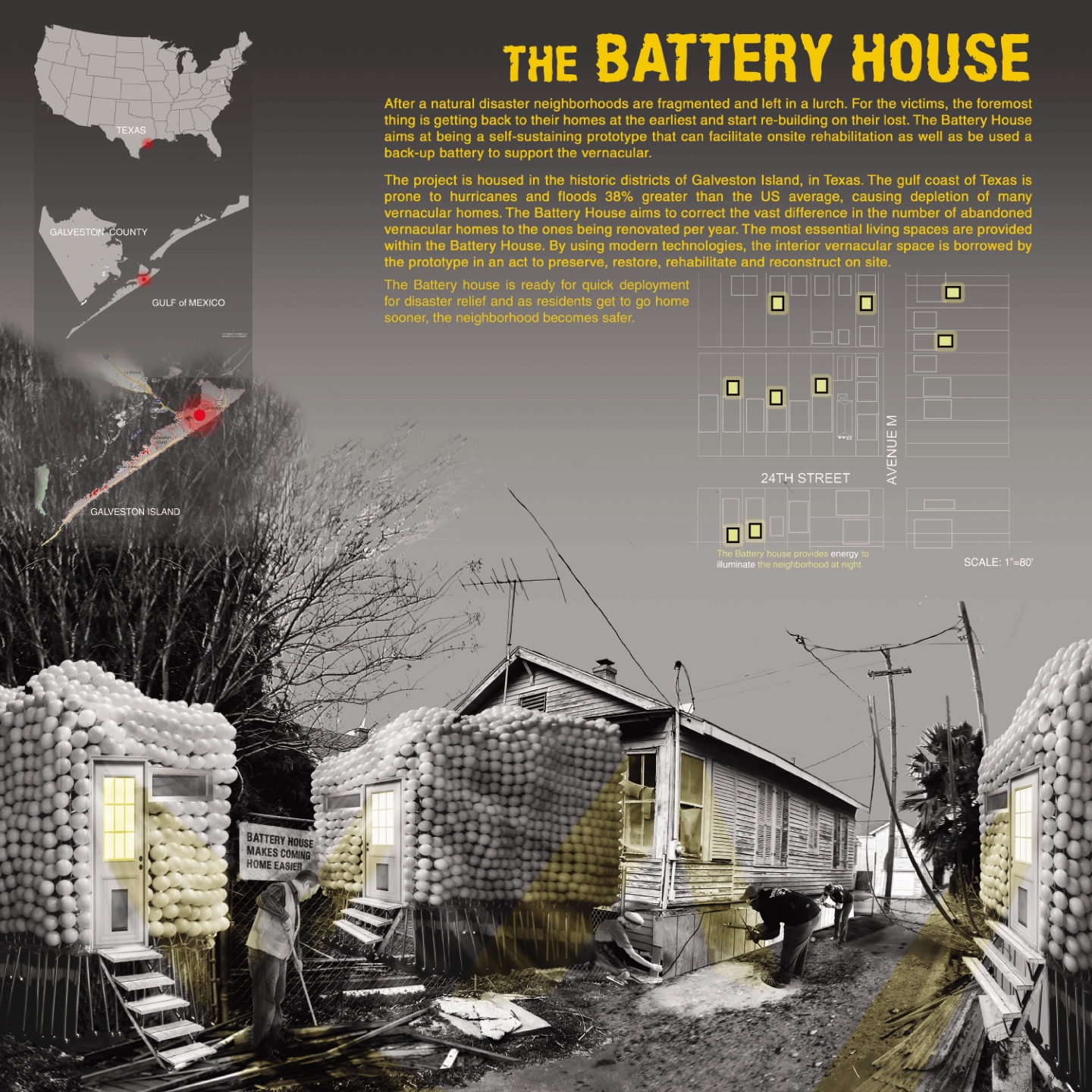

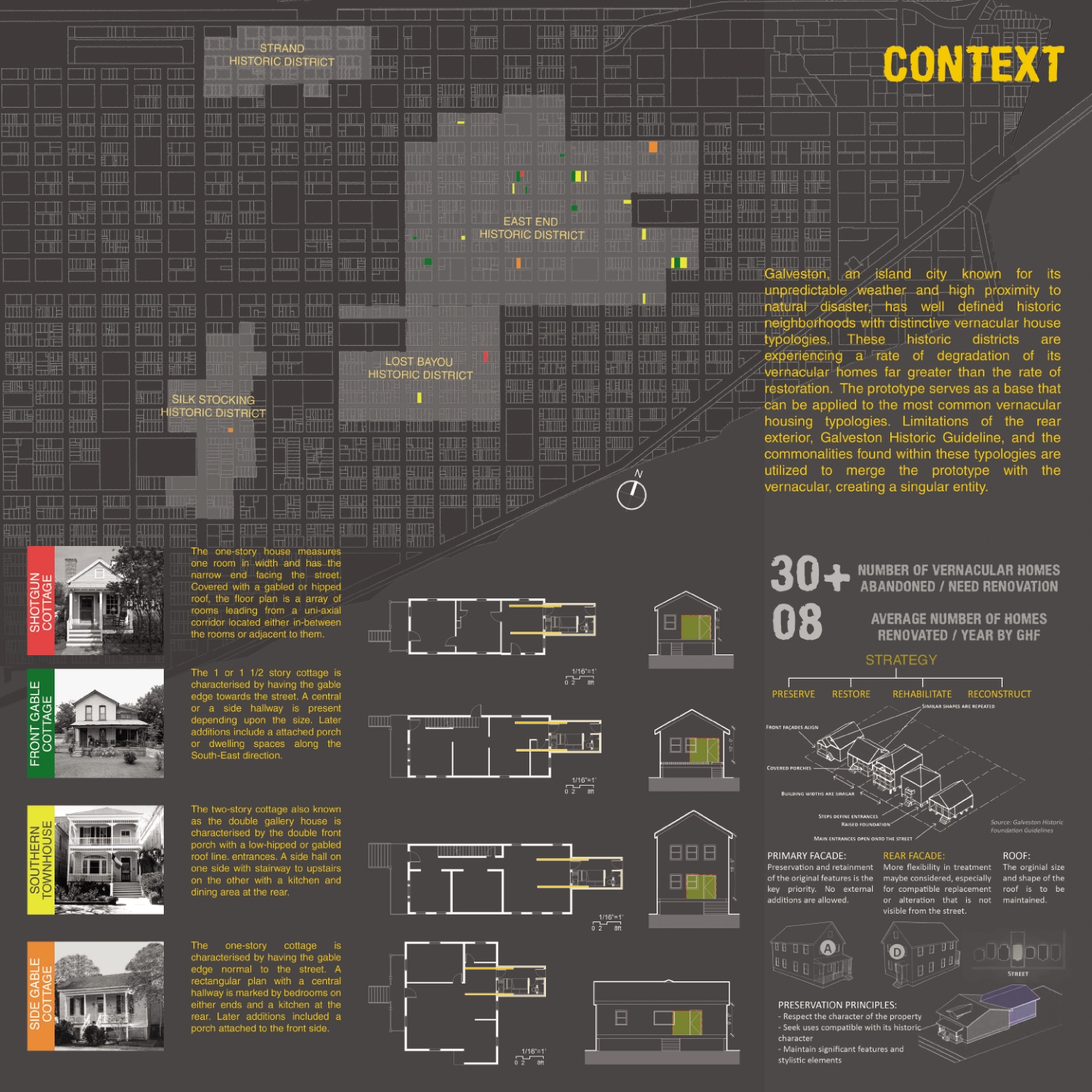

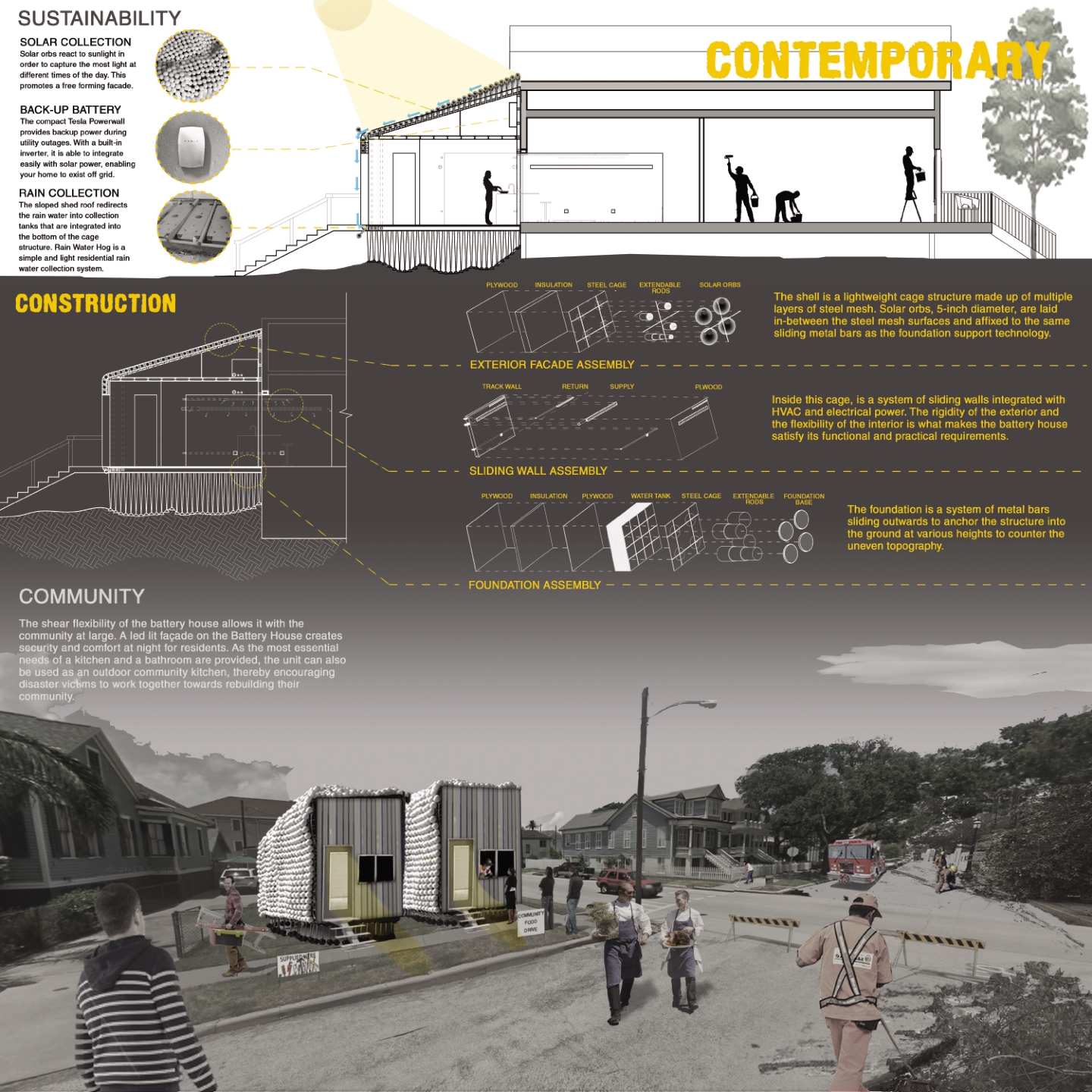

THE BATTERY HOUSE

Students: Homa Ansari, Anmol Kollegal, & Timothy Massa, University of Houston

Faculty Sponsor: Zui Ng, University of Houston

Participating Schools

The competition had over 560 participants from the following schools:

California State University, Long Beach; Carleton University; Carnegie Mellon University; Catholic University of America; Cuesta College; Drexel University; Dunwoody College of Technology; Erie Community College; Ferris State University; Hampton University; Illinois Institute of Technology; Iowa State University; Kansas State University; Laurentian University; Mississippi State University; New York City College of Technology; NewSchool of Architecture and Design; North Carolina State University; North Dakota State University; Prairie View A&M University; Pratt Institute; Ryerson University; Savannah College of Art and Design; Southern Illinois University; Texas A&M University; The Cooper Union; The University of Colorado Boulder; Universite de Montreal; University Laval; University of Arkansas; University of Calgary; University of California, Berkeley; University of Cincinnati; University of Florida; University of Hawaii At Manoa; University of Houston; University of Illinois at Chicago; University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign; University of Kentucky; University of Massachusetts, Amherst; University of Memphis; University of Nevada, Las Vegas; University of North Carolina at Charlotte; University of Tennessee-Knoxville; University of Texas At San Antonio; University of the District of Columbia; University of Virginia; University of Washington; University of Waterloo; University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Virginia Tech; & Washington State University

Questions

ACSA Competitions

competitions@acsa-arch.org

202-785-2324

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL