Where Are My People? Hispanic & Latinx in Architecture

Where Are My People? Hispanic & Latinx in Architecture

Kendall A. Nicholson, Ed.D., Assoc. AIA, NOMA, LEED GA

ACSA Director of Research and Information

October 9, 2020

As architecture continues to reckon with the harm and complacency engendered by the hands of designers, ACSA continues exploring the intersection of race and architecture. Where Are My People? is a research series that investigates how architecture interacts with race and how the nation’s often ignored systems and histories perpetuate the problem of racial inequity. Hispanic and Latinx in Architecture chronicles both societal and discipline specific metrics in an effort to highlight the experiences of Hispanic and Latinx designers, architects and educators. This research report follows the first part of the series, Where Are My People? Black in Architecture.

This time we are asking a different set of questions. Why is it that the largest community of color still makes up such a small percentage of the profession? What happens to Hispanic and Latinx students after graduation? Why is it that the education of Hispanic and Latinx students in architecture is largely relegated to a few institutions? Let’s start with the history.

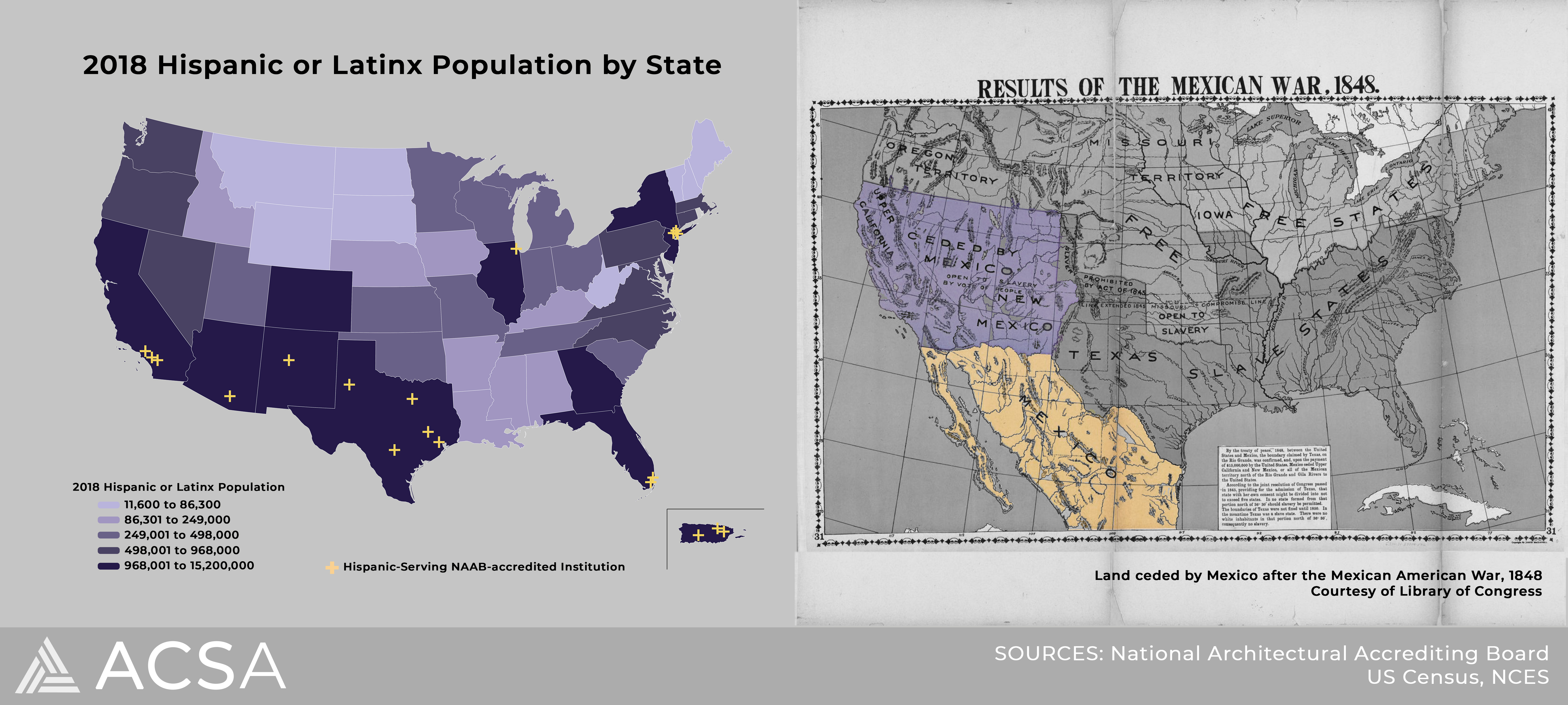

Once noted as the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States, the Hispanic and/or Latinx population still holds the title for the youngest major racial or ethnic group today. The Pew Research Center reports that nearly two-thirds of all Latinx people living in the United States were born in the United States. Regardless, the history of immigration is important. The story of White supremacy in this context largely dates back to the Mexican-American War which lasted from 1846-1848. This war was the result of then President James Polk’s desire for the United States to span from the east coast to the west coast. This war resulted in the annexation of Mexican territory which extended from modern day California to modern-day Texas. The racial classification of Mexican Americans was not as standardized as it was for Blacks. Whether they were classified as Caucasian in some places or Indian in others, they were still the subject of segregation, deportation and legislative attacks on the Spanish language. The stigmas associated with Mexican Americans still persist today with the common stereotype of being undocumented immigrants. The graphic above shows each state as indicated by the number of Hispanic/Latinx people who reside in that state. Also noted is the location of the 20 architecture institutions accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) who hold the designation of Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI).

Much like the story of Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans also became a part of the United States by way of a war and the concession of land. Puerto Rico’s history as a U.S. territory begins at the end of the Spanish American War in 1898 when Spain ceded the island to the United States. It wasn’t until the Jones Act of 1917 that Puerto Ricans were made citizens but they were not granted the right to vote. Moreover, Salvadorans and Cubans, the next two largest populations of Latinx origin in the U.S. also have blemished historical relationships of the United States welcoming them to our southern coast by way of refuge from communism or natural disaster.

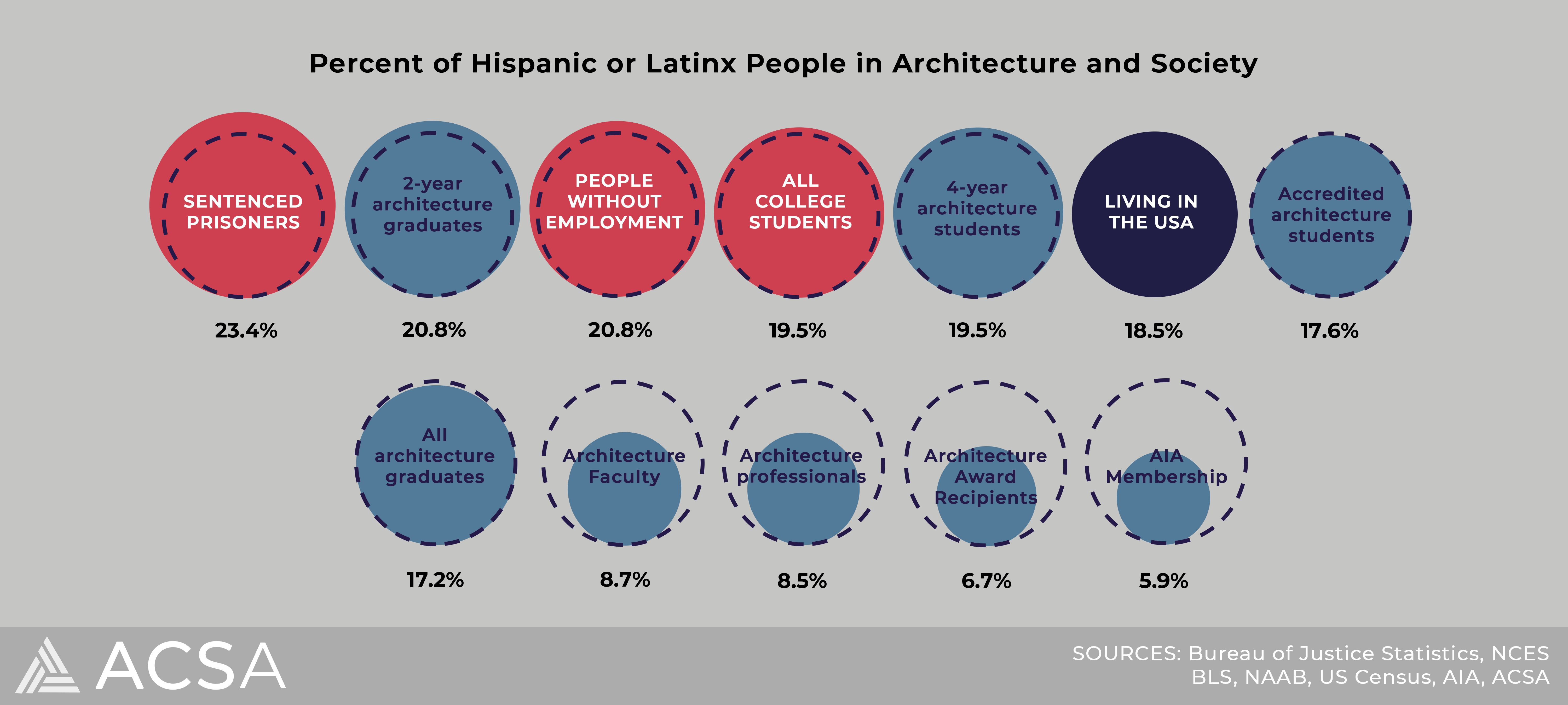

The US Census reports that 18.5% of the US population identifies as Hispanic or Latinx. The graphic above explores the representation of Hispanic and Latinx people in society as well as the architecture pipeline. Noteworthy is the enrollment of Hispanic/Latinx people in 4 year programs at NAAB-accredited schools. This matches the percent of Hispanic/Latinx students across all colleges and universities and is only exceeded by the percent of graduates from associate degree programs in architecture. Unfortunately, that parity is overshadowed by the fact that Hispanic/Latinx people make up 21% of people who are unemployed and nearly one-fourth (23.4%) of the sentenced prisoner population. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Hispanic/Latinx men, in particular, are 2.6 times as likely as their White, non-Hispanic counterparts to be imprisoned.

In regards to the architecture pipeline, data reported from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) and NAAB show little difference between the percent of Hispanic/Latinx students enrolled in accredited programs and the percent of students who graduate from all architecture programs. Where the discipline sees a real disparity is in the percent of Hispanic/Latinx architecture faculty (8.7%) and professionals in the workforce (8.5%). Moreover, the percent of AIA members and architecture award recipients are nominal. As is the case for women and Black people, data for architecture’s highest honors (AIA Gold Medal, AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion, Pritzker Prize, and ACSA Distinguished Professor) highlight a lack of recognition. Each award has a longstanding history of being awarded to predominately White men, with the ACSA Distinguished Professor designation being the most diverse. On the whole, these statistics indicate that while schools are currently enrolling Hispanic/Latinx students at adequate numbers this does not transfer directly to the profession.

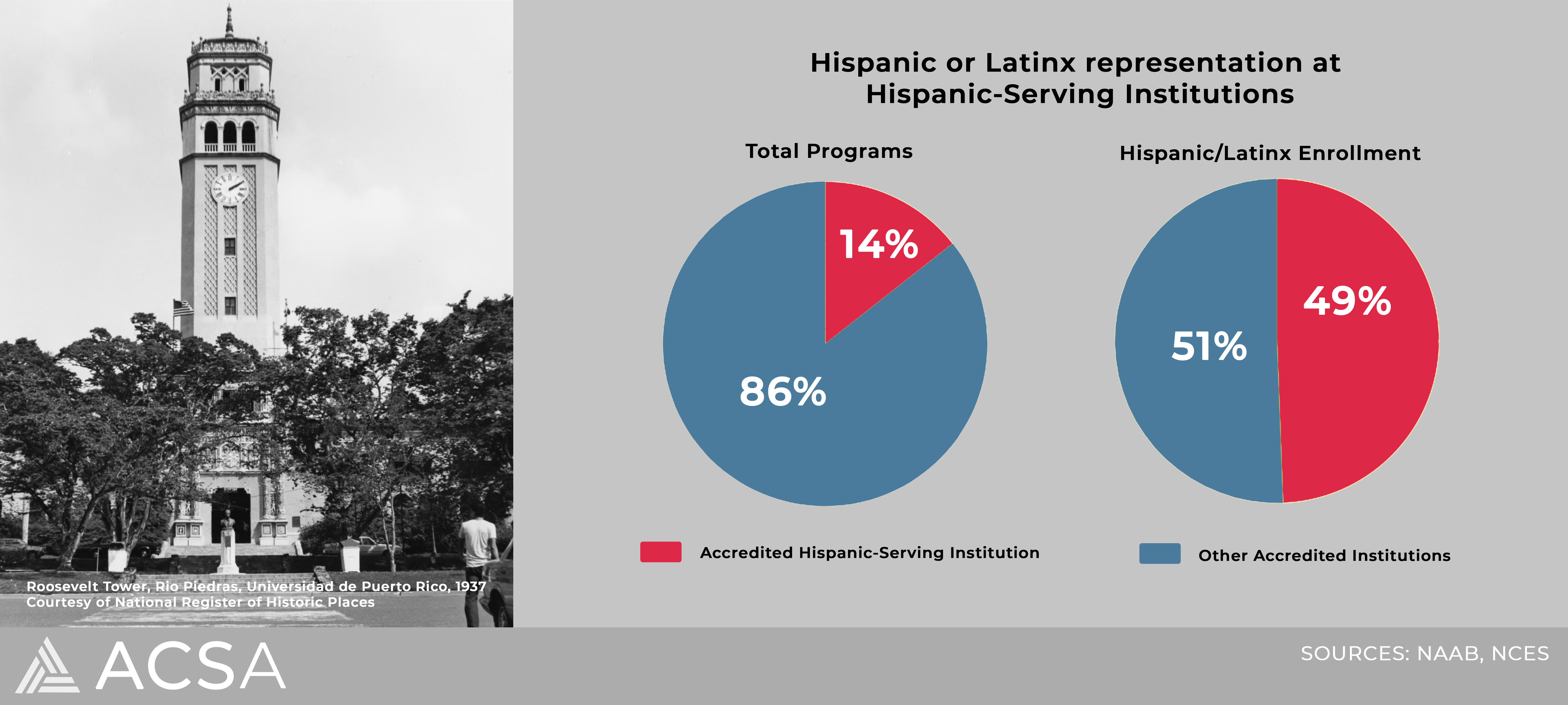

An exploration into where Hispanic/Latinx students enter in the academy uncovered the significant role Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSI) play in recruiting Hispanic/Latinx students to architecture. Of the 139 NAAB accredited schools of architecture, 20 are HSIs. While those schools make up 14% of the NAAB accredited schools, they enroll 49% of the total Hispanic/Latinx student population in accredited and preprofessional programs. Consequently, the average program offered at a NAAB accredited institution only graduates 5 Hispanic/Latinx students each year.

As previously mentioned, the Hispanic and Latinx community is extremely diverse and as such ACSA recruited a convenience sample of 100 architects, designers and educators in an effort to accurately communicate the lived experience of people across the discipline. Because “Hispanic” and “Latinx” are not races but rather ethnic labels based on geographical and cultural commonalities, we wanted qualitative data to help explain the nuances. For example, the racial make up of Puerto Ricans includes a mix of European, African and Native ancestry which shows in the complexity of the survey results. The experiences of individuals of Latin or Hispanic origin are quite varied. The qualitative research below uncovered discrimination and colorism, the importance of family and community, as well as pride in the rich legacy of Hispanic and Latin people across the globe.

When we asked survey participants what it means to be Hispanic or Latinx in architecture, while many cited the need to emphasize community or a lack of representation, the most frequent theme that emerged was the responsibility to be a cultural liaison. This manifested as a desire to hold on to one’s Hispanic/Latinx roots but also communicate the importance of that heritage to architecture at large. Additionally, there was a sense of pride in the acknowledgement that despite feeling misunderstood or undervalued, being Hispanic/Latinx in architecture is hopeful.

When we asked participants about an area or issue that was important but often devalued across the discipline respondents overwhelming cited ‘community’ and ‘family’. Responses mentioning the need for community ranged drastically in scale from a sense of community felt in the workplace to the community at large, across the country. Many participants even went as far as to suggest ways to build community, citing mentorship, design ethos and interdisciplinary collaboration. Family was also noted as something that suffers as a result of architecture. Many Hispanic/Latinx men and women noted the hardship of trying to keep a work/life balance and how families support the larger sense of community previously mentioned. There was also a stream of responses that called attention to generational connectivity. Some talked about the need to be the change in the profession for Hispanic/Latinx children and others talked about sentiments of respect for elders and ancestors. The idea of family as a cultural value is supported by research in sociology and anthropology. Experts call this belief that the family unit is central to the Latinx way of life, familism. Researchers, studied this phenomena among Hispanic/Latinx and White teens and found that while White Americans considered educational success and hard work as a means of gaining independence from their families, Hispanic/Latinx teens considered high levels of achievement necessary as a way to take care of their families.

Lastly we asked survey participants about how and when they realized their racial identity. Two of the largest themes that emerged were ‘disorienting experiences’ and the ‘lack of representation’ in the profession. Participants reported to be disoriented when they left more traditionally Latinx environments. Many commented on the experience as a part of coming to the United States or to the mainland US. For many participants, they were coming from an environment where they were part of the dominant culture and, as such, where shocked by the stigmas and microaggressions they experienced as part of an underrepresented people group in the US. Participants also noted the feeling of being labeled, judged or ignored whether it be for their intangible mannerisms or the identification of their accent. On the contrary, participants commented on the phenomena sociologist call racismo, which is akin to colorism. Lighter-skinned participants sometimes identified themselves as such and often had less concrete examples of realizing their racial identities understanding that they held some advantage for being Hispanic or Latinx in ethnic origin but racial identifying as White.

Questions

Kendall Nicholson, Ed.D.

Director of Research + Information

202-785-2324

knicholson@acsa-arch.org

Study Architecture

Study Architecture  ProPEL

ProPEL